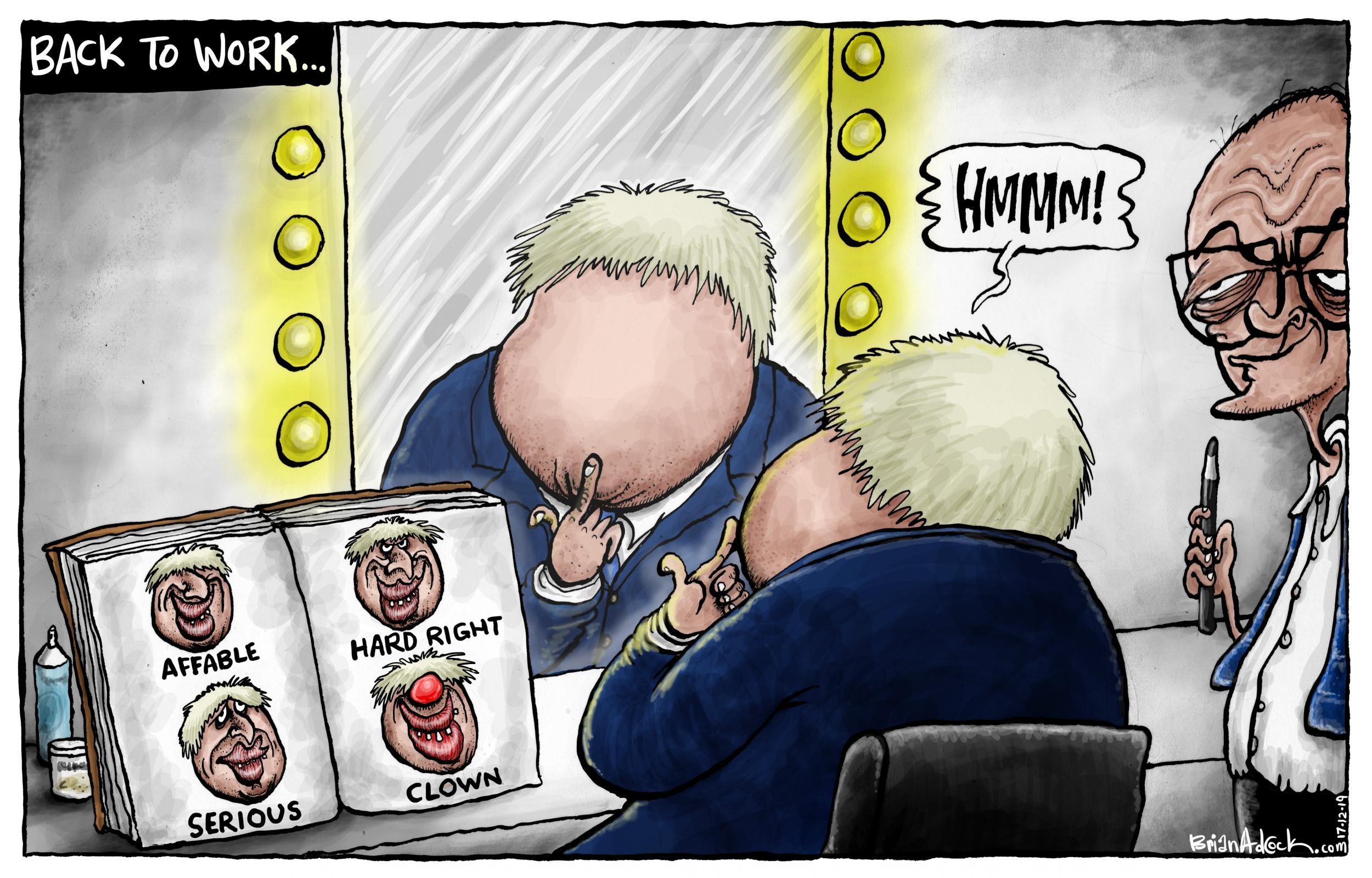

Is now really the time for Johnson and Cummings to further disrupt the workings of government?

Given the upheaval in our economic relationship with Europe, the prime minister’s adviser may come to regret his latest plan

Britain’s “Rolls-Royce” civil service has its detractors, but few are as contemptuous of the mechanics of government as Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s adviser. Now, according to reports, he will be able to test out some of his more outré theories about how government should work in a real-world experiment. For Mr Cummings is going to take personal charge of defence procurement, and the wider, and even more difficult, job of reforming Whitehall and Downing Street.

Fearsome as his reputation is, this may not be entirely bad news. The danger is politicisation, but, on the face of things at least, Mr Cummings is more interested in efficiency and professionalism than in rigging the system in the Tories’ favour. Some of his ideas are ideology-free, such as melding foreign and defence policy.

That is overdue. For decades Britain’s foreign policy aims and defence capabilities have been at best uncoordinated and, at worst, entirely at odds. Perhaps the most potent symbol of this is the commission of two extremely expensive aircraft carriers, that most traditional method of projecting naval power. We know already the embarrassing truth that they may have to operate without any aircraft to carry for a time; but the broader question – “what are they for?” – has not been answered. Post-Cold War, in the age of terror and cyberattacks, they do look a bit clumsy. If Britain wants the royal navy to help the Americans patrol the South China Sea to reassure the Japanese, that’s fine – but ministers need to take account of how such activity affects our putative trade deals with some of the world’s biggest economies.

However, the rumour that the Department for International Development (DFID) is to be abolished and rolled into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is a disquieting one. It is one of the few examples where a symbolic commitment to a given policy – devoting 0.7 per cent of GDP to development – requires the commitment of a single ministerial and official team. DFID is there to protect that commitment, and it is an important one, even surviving inside the Conservative manifesto.

Mr Cummings is not going to be given the Ministry of Defence’s £42bn budget to spend as he sees fit. What he will be charged with is giving some discipline to the process of spending taxpayers’ cash. Aligning foreign policy aims – including economic, aid and trade ones – with defence and security aims is crucial, and will be an important part of the UK-EU talks on the future economic and security partnership. And, of course, the Ministry of Defence, in common with defence departments around the world, has proved itself capable of prodigious waste and duplication, both in the UK’s own decisions and in its attempts to coordinate with Nato allies.

As for the rest of the home civil service, there is at least a case for review and reform. Ever since the Fulton inquiry half a century ago there has been concern at the “cult of the generalist”. The notion, say, that a bright spark with a first in Classics from Balliol can walk into the Department for Transport and hope to help manage complex infrastructure projects has always been a problematic one (such characters, including Boris Johnson, are better off at the retail, political end of governance).

In France there has long been a tradition of professional training for public administrators – the so-called Enarques, named after the Ecole Nationale d’Administration. The Enarques think of themselves, rightly, as a kind of elite, and of course the current mood is against such self-regarding, self-perpetuating cliques; then again, endowing the people who try to make policy with some rudiments of accountancy, public law, project management and communication and software skills may be no bad thing.

The usual fate of outsiders attempting to reform the civil service is marginalisation. The silky mandarins of Whitehall are skilled at embracing interlopers, making friends rather than engaging in hand-to-hand combat with their critics, watering down reports, shelving more tricky decisions, leaking and generally making sure as little as possible changes. In every bureaucracy, especially public ones, it is always far easier to stop something happening than to make it happen, as Mr Cummings and his patron, Michael Gove, found during their time at the Department for Education during the coalition.

Apparently the cabinet secretary and head of the civil service, Sir Mark Sedwill, is enthusiastic about Mr Cummings’ ideas, which either means he will smother them to death with love, or that the civil service really is on for some historic changes in culture and practices.

That said, they will have to do better than simply moving bunches of civil servants around the jumble of government offices of Whitehall and changing the plaques on those elegant Edwardian facades. MOG, or “machinery of government” changes are almost routine in Whitehall, with departments or responsibilities – such as business, skills, trade, training, immigration and industrial strategy – split, merged, reinvented and relocated with almost the frequency of cabinet reshuffles. The lack of political stability does not help: since the 2015 election, for example, there have been no less than seven secretaries of state for work and pensions: Iain Duncan Smith; Stephen Crabb; Damian Green; David Gauke; Esther McVey; Amber Rudd; and Therese Coffey. This may be one small factor in the failure of universal credit. (Even Mr Cummings isn’t mad enough to go near that one).

Departments come and go, but 10 Downing Street and the Treasury always stay in charge.

The exact benefit of all the mergers and demergers in government departments is far from clear. It is usually a bad sign when a prime minister creates a special department and cabinet position (or, more often, minister with a right to attend cabinet) for some pet scheme or other, as it means that there will be no funding and no political capital being expended on it.

Much energy, for example, will be devoted to merging the Department for International Trade and the current Business Department, which will leave it with more or less the same role it had when it was called the Department of Trade and Industry back in 1970, before it was reorganised a half dozen times to zero effect.

Without sounding too much like an archetypal Sir Humphrey, it might also be queried whether, at a time of such upheaval in our economic relationship with Europe, this is the best moment to further disrupt the workings of government. It might be argued, for that reason, that this is precisely the right moment – were it not for the government’s self-imposed deadline of 31 December 2020 to conclude an ambitious trade and security treaty (including ratification in about 30 European national parliaments and regional assemblies). Mr Cummings might also want to reflect on how the biggest single innovation in the public sector in the past 30 years – the private finance initiative – was implemented.

Mr Cummings is a clever and resourceful man, with a commendable work ethic that is an example to all in what he’s termed the “decrepit machine” that is 10 Downing Street. Yet even he is capable of strategic overreach.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments