I was on the Windrush, taking the biggest gamble of my life (for love)

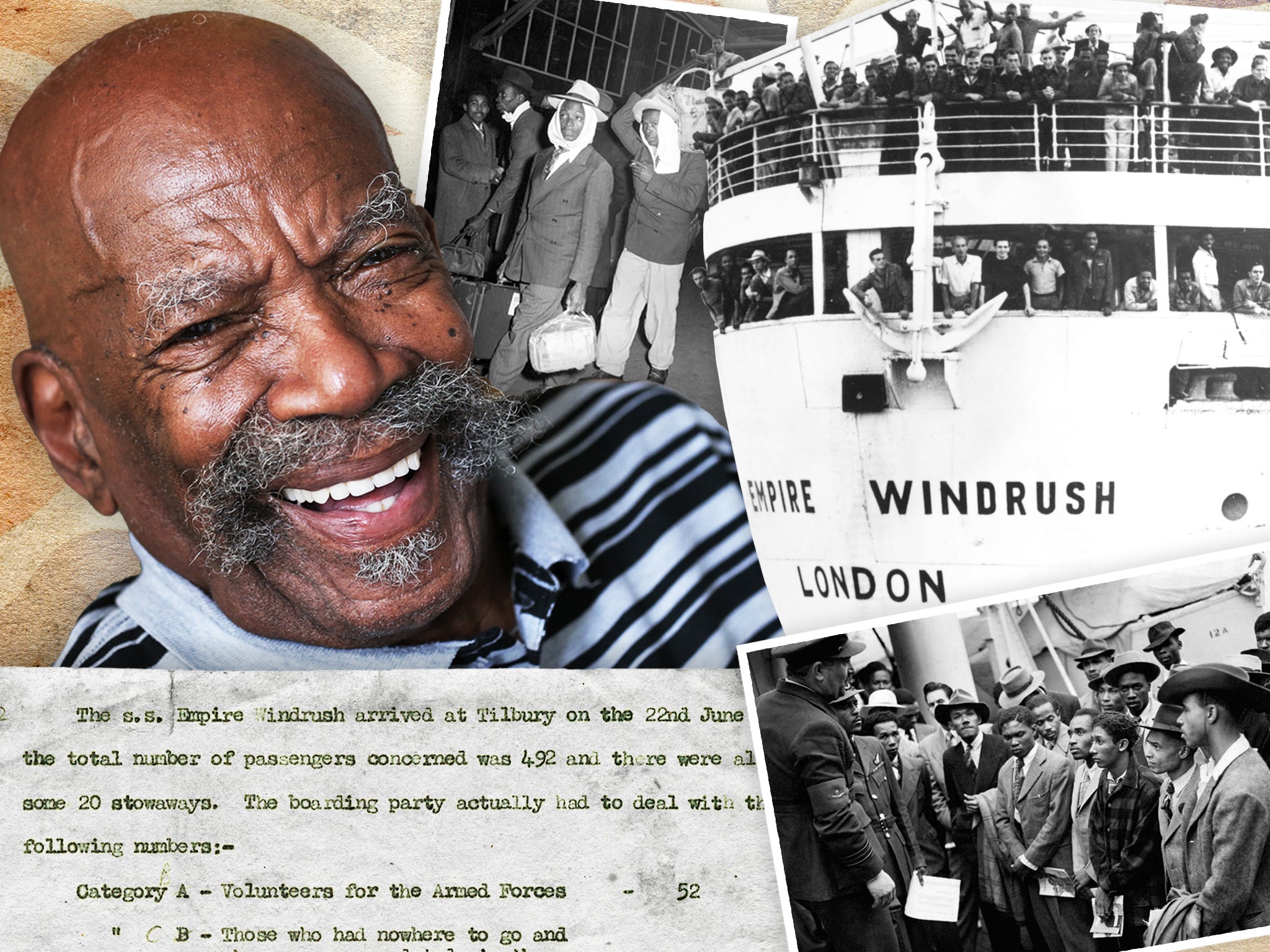

As one of only two surviving passengers from that first Windrush voyage, Alford Gardner, now 97, speaks to Nadine White ahead of the 75th anniversary of a momentous sailing that changed thousands of lives and left a huge legacy in British society

Alford Gardner has been a gambler all his long life. The 97-year-old has taken a risk, whether in cards, in love – or in his future.

And so it was in 1948 when he paid £28 and stepped on board the HMT Empire Windrush, bound for England.

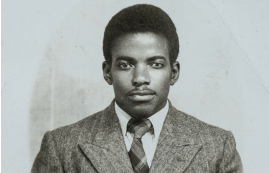

The 22-year-old from Kingston, Jamaica, embarked on the three-week trip with brother Gladstone and hundreds of other immigrants from various Caribbean countries, but mostly Jamaica.

Though some passengers experienced nerves and seasickness ahead of the ship’s arrival at Tilbury Docks in Essex on 22 June, this wasn’t the case for Alford.

For him, the expedition felt like a homecoming; after all, he’d first been to Britain in 1944 as an RAF engineer, briefly basing himself in Leeds before returning to Kingston in 1947.

This second trip was light work for him. In fact, Alford’s ease at sea was such that he often volunteered to go up onto the deck to collect meals, returning with food for his peers.

“Coming over on the ship was beautiful! I was quite accustomed to travelling by sea as I’d done it before,” he says. “We stopped at different locations, picked up people, and had a happy time.

“For me, going to England was like coming home for the second time; I had some very good friends here.”

Whether in the dimly lit cabins or out on the creaky upper decks when weather permitted, the passengers’ expedition to the “mother country” was infused with nerves and excitement, spurred along by the slapping down of dominoes, enthusiastic exchanging of stories, singing of Lord Kitchener calypso songs and, yes, some cheeky gambling.

“Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, I was gambling and playing card games like poker… even though I lost a lot. And every time that happened, my brother would take over and win,” Alford laughs,

Throughout the trip, the air was thick with jubilation among the predominantly Black Caribbean passengers.

It was in poetic contrast to the circumstances of many of their ancestors generations before; something like a subversion of history. This time around, Britain appealed to her colonial subjects for their help in rebuilding the country following the Second World War ruin – and the “unlikely” heroes answered the call in earnest.

In recent years, Windrush has come to mean different things to different people but for Alford, well, it boils down to one thing: love.

“I had different reasons for coming but one special reason brought me back: I was very much in love. I met my wife in 1946 and promised I would come back for her,” he says. He kept his promise.

Not even the grey skies, as he stepped off the vessel, bothered him, he says; not when heading back to Yorkshire made him feel warm inside.

“When we arrived, it was very cold but I wasn’t worried about that because I was looking forward to coming back to Leeds,” he says. Alford had completed a training course in the area and was familiar with it.

He founded the Caribbean Cricket Club in Leeds, which also celebrates its 75th anniversary this year. For a while, he was the team’s wicketkeeper.

At the Leeds Mecca dance hall in 1947, he had met wife-to-be Norma, a tailoress, and was captivated by her looks and dance moves.

“Ah, she was a beautiful young lady and a wonderful little dancer,” he smiles. The pair got married in 1952 at a local registry office, followed by a party at their house; he was 25 and she was 21.

Alford attempted to ask permission for marriage from Norma’s father but he made it clear he didn’t approve of his daughter marrying a Black man.

“Norma’s father didn’t want to know me at all,” Alford explains. “As soon as he came into the living room and saw me, he shouted, ‘Get him out of here!’ So I just turned and walked out but she said, ‘I’m coming with you’.

“We had a party in our house with all our friends... we had a good drink and a good dance. The father didn’t want to know me but one thing about him is he loved his grandchildren.”

After nine children (one of whom was stillborn) and 30 years of marriage, they split in 1982 – owing to his “rogue ways”, by his own account – and Norma died in 2013. “Unfortunately, things happened in life but we had some beautiful memories.”

Racism

Alford was confronted by a great deal of racism following his arrival back in Britain – from initial difficulty getting a job because he was Black and intimidation attempts when he did find work to struggles securing accommodation and people disapproving of his relationship with a white woman.

“I experienced racism throughout my life – there was no getting away from it – but I tried my best not to let that bother me,” he explains.

“I would avoid going to places where I knew I wasn’t wanted. If I went into a place and realised it wasn’t my type of place, I’d be off.”

Then there were some white people who felt the new arrivals were “stealing their jobs” – similar to the anti-migrant rhetoric we hear today.

“When we came back to England in 1948, we came to help rebuild the country and not come to steal the jobs of the people of the United Kingdom,” he says. “Lots of people didn’t understand that. There were a lot of idlers who didn’t want to work but then hated to see people coming in and finding work.

“I thought, ‘good luck to them’ and didn’t let any of that bother me; I got a job and worked hard. I’ve always worked hard. I had a family to take care of.”

Ahead of Windrush 75, which marks the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, polling by the British Future think tank has highlighted that two-thirds (67 per cent) of ethnic minority Britons feel this country has a long way to go in achieving race equality, as Black and Asian people face discrimination in their everyday lives in Britain.

Seven decades later, Alford feels that progress has been made over the years.

“The racism used to be a lot worse than it is now. Things have improved but there’s still a long way to go.

“Britain is alright; things are different these days.”

Alford who retired in 1981, speaks of his childhood years in Jamaica with immense fondness.

One of 11 children, his parents Lavinya and Edward Gardner moved from their native Kingston, residing between the St James coast and its capital, Montego Bay.

“Growing up in Jamaica, every day was memorable,” Alford says. “I lived a life of beauty; there were no problems.”

“My parents were very strict but my mum, in particular, was also very loving. Mama was a beautiful woman and always seemed to know where I was and what I was doing, whether I was near or far, and what time I was coming home.

“ln my life, I’ve had beautiful women around me from my mum and grandmother to my aunties.”

Of his many siblings, one sister and brother are alive – Pamela and Samuel – and both live in America.

As Britain gears up to mark the 75th anniversary of Windrush, many are reflecting upon the contributions those Caribbean pioneers have made.

“Times flies. It’s been 75 years already? I couldn’t tell you where the years have gone,” Alford says, musing that it feels like “yesterday”.

However, many feel that the occasion is bittersweet after the emergence in 2017 of the Windrush scandal. Many British citizens, mostly from the Caribbean, lost homes and jobs, were denied access to healthcare and benefits and were threatened with deportation despite having the right to live in the UK.

Alford is clear the Home Office wronged the victims and feels this needs to be rectified.

“People are still waiting for compensation,” he says.

At almost 100 years old, and as one of just two surviving passengers who made that first Empire Windrush journey, he is full of zest for life and looks forward to his daily trips to the bingo hall.

“It passes the day; sometimes I win and lose, but it’s fun. I’m too old to do gardening though I’ve always enjoyed it, so I go and relax at bingo for a few hours.”

With all being well, he will head to Jamaica in July, where he can have “all the ackee and saltfish, gungo peas, yam and banana” he wants.

“I’m happy with the life I’ve led over the years but only one thing is missing: money,” he says.

“There are things I’d like to do, family outside of Leeds that I’d like to spend time with, but I don’t have it [the means].”

As far as his greatest legacy is concerned, this Windrush voyager sees himself as “someone who loves his family from the oldest to the youngest”.

“I’ve raised my children to know the importance of staying true to themselves. I love my family and grew up in a big one, myself; I’m glad to see that my children have done well.

“Ever since I’ve known myself, I’ve lived by three things: family, music and sport,” he said, adding that he spent his childhood years as part of his local church choir.

“I love cricket and football; I’ve tried everything, though I’m not good at any of them. Music changes over the years but I love everything that sounds nice.

“Though, you can’t beat a good choir – my favourite is the ‘Hallelujah’ chorus. I love a good pipe organ and bagpipes playing a good tune.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments