‘I protected the most trusting and simple people from the one-armed bandit gambling mafia’

Business and finance has become second nature for Alexander Lebedev, who has seen economic corruption first-hand. Here, in the last of three extracts from his new biography, he recalls his condemnation of Russian oligarchs and his disdain for ‘financial crooks’

I hope Henry Reznik was not too upset. He defended me brilliantly during the trial, and it should be mandatory for students and experienced lawyers to attend his speeches in court. The judge listened to him attentively, although the young girl from the Prosecutor’s Office probably had no idea what he was talking about. Someone had evidently just asked her superiors what was happening and recommended a particular course of action. I had no difficulty understanding the subtext of the verdict: this guy is not about to run off abroad, and what’s the point of sending him to rot in prison? The investigation and the trial itself had already been sufficient punishment. He’s got three children, two of them minors.

For “battery” I was, nevertheless, sentenced to perform 150 hours of community service. I could easily have avoided even that penalty. We did, needless to say, appeal the sentence in the Moscow Municipal Court and there was a second trial. The last session was scheduled for Friday 12 September 2013. If on that day I had simply not turned up in court, the statute of limitation would have terminated the case automatically, because the “crime” (according to the official version in the verdict) had been committed two years previously. To do that, though, I would have had to pretend to be ill and obtain a false medical certificate, or arrange some reason why the lawyers were unable to attend.

I decided to force a definite verdict, a course of action that from the point of view of pragmatic logic was verging on imbecility. However, it was clear that I would not be receiving a more severe sentence, the most threatening outcome had been left in the past. It is not pleasant when you have a family, children, plans for the future, to be constantly recalling that you are shortly to be imprisoned for several years for a crime that you quite obviously did not commit.

At the height of the trial, when I really did face the prospect of seeing the world from behind bars, I wrote entirely seriously to Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev asking him, within the framework of the anti-smoking campaign, to ban the imprisonment of smokers in the same cell as nonsmokers. I was readying myself. The letter had no useful impact. Perhaps our sport-loving president should start a campaign against the smoking of the 750 billion cigarettes annually manufactured by America’s tobacco monsters.

The idea of working for the benefit of the village of Popovka, where my National Land Company has its headquarters, occurred to me as soon as it was clear I had managed to avoid jail. My home address was registered as being in the Basmanny district of Moscow, and in theory that was where I should serve my punishment. One more manual labourer was, however, hardly going to make much difference to the Muscovites. The capital’s housing and communal service already have plenty of guest workers prepared to clear the streets of mud and snow, and in the process hand over part of their salary to whoever expects them to do so. All they would get from me would be a lot of aggravation.

I therefore rented a house in Popovka and officially changed my place of residence: today that is a simple matter of notification. This obliged the Federal Penitentiary Service to transfer the case to their department in Chern district of Tula province. Our company had been maintaining the local children’s day care centres for the past eight years as the state could not afford to. I correctly calculated that the local branch of the FPS would never have had to deal with someone with such an untypical sentence. In 99.99 per cent of cases, those before the courts are imprisoned, and any others get acquitted. Accordingly, they were unable to find anything else for me to do than toil on our own “collective farm”.

And so in December 2013 I set to work renovating the children’s day care centre, which in any case we needed to put right. On the first day of my community service, the media turned up in force. The national television channels sent cameras and did live broadcasts. It was practically the top news story of the day. Given that previously I had never been featured on state-run television to my advantage, the coverage was fairly positive. Here was a rich oligarch redeeming his guilt through manual labour in his native land.

The greater number of journalists declined, but some still visited. Komsomolskaya Pravda’s correspondent in Tula, Alexey Tumanov, actually moved to Popovka, wrote daily reports, and helped me with the work. We set out a new playground for the kids and finished renovating the inside of the building. We made a mini-football stadium. The village authorities have no money for such “luxuries”. The entire budget revenue for Popovka was 6m rubles ($200,000). They had debts for electricity and problems with water pumping stations, and renovating a day care centre for the children was going to cost in the region of 10m rubles ($333,000). This was where A Lebedev, felon, came in useful.

There are a lot of children in Popovka now. They flock to the day care centre in new, smart clothes. Thanks to our farm, the villagers have started earning money and Popovka is no longer moribund. You can tell that from the houses. They are newly painted, sheathed in cladding, and almost all have satellite dishes.

Elvira Goryukhina is one of my favourite journalists and has been observing the evolution of Popovka for many years. Here is what she wrote: When you reflect on the phenomenon of Maxim Gorky Ltd, the main thing that strikes you is the wisdom of not destroying what is already there, not destroying village life, which is where large conglomerates often start. In Popovka they did not padlock the old farm office. Without doing away with the existing system, the “newcomers” have put money in the production process and advanced technology. Elvira Nikolaevna is right. In the countryside you can see your investments yielding a new harvest of homes, of smiles on people’s faces. That is what money is really for.

Forbes magazine was first published in 1917, a momentous year in world history. It very superficially believes that having a fortune is a great boon, and has no inclination towards moral judgement

Victor Pelevin has a story, “Friedman’s Space”, in which the intelligence agencies’ special services send money-laden “buckonauts” (by analogy with cosmonauts) beyond the “Shvartsman horizon”, where there is a corridor that alters human psychology. Alas, money remains for the majority the main criterion of both human ability and character, and also of the talent of scoundrels and swindlers.

I was reminded of this when I learned from lawyers that the latest issue of Forbes magazine had my name on its rich list with a valuation of $1.6bn. I was not a little surprised, and considerably more annoyed. That day the American lawyers themselves surprised me a lot. They suddenly became much more attentive, not to say obsequious, and also more eager to give the appearance of being very active.

Forbes magazine was first published in 1917, a momentous year in world history. It very superficially believes that having a fortune is a great boon, and has no inclination towards moral judgement. Its journalists are not interested in where money comes from, and even less in what people spend it on. I still cannot understand how they arrive at their totals. One year my fortune had grown to $3.6bn, and then suddenly disappeared. I wrote a letter to Steve Forbes, who is the chairman and editor-in-chief, asking him to explain their methodology and not to include me in this strange rating in future. How, for example, are you to measure the fortune of an oligarch, whose indebtedness to state-owned banks of the Russian Federation might be double the valuation of the capital of his companies? By what means was Forbes magazine able to include Joaquín “Shorty” Guzmán in its list of billionaires, a Mexican drug lord who has spent his entire life outside the law? This rating is another small cog in the mechanism for transferring that trillion dollars a year out of the pockets of the poor and into the pockets of rich crooks.

I took my leave of the notorious list in 2013-15, when I said goodbye to my business interests. Everything was relatively straightforward: National Reserve Bank had deposits of about a billion dollars of its clients’ money. The bank was attacked by ill-wishers, who had no scruples about their methods. Their techniques have been described in detail above. We needed to return that money to our clients in a hurry. They were not interested in discussing postponements, and you cannot instantly sell shares in Gazprom and Aeroflot, a mortgage portfolio and real estate other than at major discounts. I had to sell assets worth $1.5bn for $1bn. They included a cultural centre near Paris, A-321 planes, a Global VIP jet, an apartment in London, and buildings in Moscow and St Petersburg. However, having repaid our clients their money to the last penny, I retained my reputation. I proved that, if you do business honestly, you can repay all your depositors even in the most acute run on your bank.

Today National Reserve Bank is not a business, it is a showcase. It owes nothing to clients, does not accept prepaid liabilities, does not make loans or buy securities, and it does not take risks. It survives by placing its capital in Savings Bank of Russia on the interbank market. A more solid bank is inconceivable: it can be destroyed only by nuclear war. It stands as a mute reproach to the individuals who have filched $100bn from the 900 Russian banks they deliberately bankrupted since 2006, and who believe that in our country reputation counts for nothing. I will not deny that this very thought did often cross my mind at those times when, since I was young, I was jealously guarding my honour.

Why would I, having spent the same amount not on a yacht but on the world’s biggest potato farm, join in the jubilation of the German shipwrights? I do not like yachts, villas, private jets and similar luxury goods, whose purpose is merely to demonstrate an ostentatious superiority over the ‘suckers’. I protected the most trusting and simple people from the one-armed bandit gambling mafia by dragging a law through the State Duma. I sank €200m in Crimea rather than in the Maldives or the Côte d’Azur, and returned to my bank customers the full $1bn they had entrusted to me. I want to invest in a network of Petrushka cafes, where my compatriots will be able to eat healthy food at an affordable price. This book aims to explain some aspects of my motivation. Do I have allies? Time will tell.

My Manifesto

Oligarchs, semi-oligarchs, would-be oligarchs, corrupt officials and their numerous retinues of staff come out to graze in the south of France in the summer and disport themselves in Courchevel in the winter. Is it possible that the wily French authorities have arranged this deliberately – this whole vanity fair which is yours to command? Beneath the palm trees and the gentle sun, this fauna bears a striking resemblance to the Papuans of the Wamena tribe, among whom I lived during my trip to New Guinea. Men of this tribe wear a holim to cover their manhood, a hard cover from the shell of a tropical fruit. European tourists gaze in amazement at the diversity, configuration and, most importantly, dimensions of these holims, the size of this phallic simulacrum proclaiming the social status of the male. In fact, the women of the tribe say, it’s all just for show, like the yachts in the Monaco marina.

The indigenous French population views some of the Russian parvenues with a degree of bafflement and ill-concealed contempt. No wonder that some of these Russian crooks have been robbed in their villas, and not only once. Much of it is an ostentatious sham. Behind it is cynicism and envy, loathing and servility, and always straightforward human fear. In the subcortex of every monstrously superior movie-set alien squandering hundreds of millions, there lurks an awareness that his status symbols have been bought with someone else’s money, money embezzled from the state, from a bank’s customers, or skimmed off some loan. On their home planet some could at any time be seized by the holim and carted off to lie on a gruesome bed of nails. Alternatively, some local French wizard may tire of the sight of tsome of hem and turn these casino-crazy extra-terrestrials into cacti.

In 2003, during President Vladimir Putin’s visit to France, a major event was held at our cultural centre near Paris. Pyotr Fomenko’s company presented his take on War and Peace for the visitors. I was keen for the cultural centre to be talked about on the national channels of Russian television but, to my regret, I was not seeing eye-to-eye with Ambassador Avdeyev and things turned sour. Instead, a different building was featured on Russian TV, an exact replica of the Washington White House, which a Russian oligarch had bought in the south of France. I asked the oligarch afterwards, “Don’t you see this does nothing for the reputation of our business class? The yacht, the new villa ... Is it really not possible to come up with something a bit different: restore a historical monument, create an art and culture centre, instead of buying your twenty-fifth property for $100m? That’s downright sad! And that’s the reputation it will get you.” His response was, “You know, I don’t sleep well anywhere. With every new purchase, I hope my sleep will improve.” No doubt he was joking, but the pointless extravagance continues.

How did the pseudo-state of Monaco appear on the map of Europe? On 8 January 1297, Francesco Grimaldi, a scion of one of the ruling families of Genoa, seized a castle on a cliff on the Ligurian Riviera. It was all rather sordid. Francesco and his comrades, disguised as Franciscan monks, knocked at the gates in bad weather, and when the guards took pity and let the “poor pilgrims” in, they whipped their swords out from beneath their habits and murdered their guileless benefactors. This incident is cynically depicted on the coat of arms of the ruling dynasty. Since then, Monaco can be considered a true offshore tax haven, which owes its existence to the commercial and fiscal privileges it provides to ‘non-domiciled residents’. Its rulers have manoeuvred between the great powers of Europe, becoming at one time a protectorate of France, then of Spain, then of Sardinia. On 15 February 1793, the French Convention decided to annex Monaco, and the principality, renamed Fort-Hercule, became a canton within the French Republic. All the riches of the Grimaldis were confiscated, their paintings and works of art sold off. The palace became a barracks, then a hospital and shelter for beggars. After the collapse of Napoleon’s empire, Monaco’s sovereignty was restored.

According to my calculations, in the past 10 years over $100bn has been stolen from Russian banks. And if that is the case, then the banking system described by Adam Smith and David Ricardo has completely ceased to perform its useful functions. All these hundreds of private banks swallowed up by the waters of Lethe have not contributed anything like a benefit to the real sector of the economy that would outweigh the damage inflicted by the fraudsters. Russia does not need so many small banks. And there is no question but that we should be fighting for the return of those 100 billion stolen dollars. They add up to more than Russia’s National Wealth Fund!

The current ruler of Monaco, Albert II, loves to dress up as the best friend of the Russian people when welcoming the owners of super yachts

The main question is – how? By hiring foreign lawyers and going through foreign courts? Well, certainly we could follow the example of the Kazakh authorities in the Ablyazov case or, as in our Russian cases, spend years and pay astronomical fees to lawyers. I calculate that, for every stolen $1bn, Russia would have to find $100m-$150m from the Russian budget and, after 10 or so years of litigation, would most probably lose. The other side would lay out $200m-$300m and get better lawyers working for it.

Even if it proved possible to freeze the assets, which, as well as being expensive, is no simple matter, it is unlikely that it will prove possible to realise them for anything like their real value. The game is not worth the candle. The money will be left in the Western banks and investment funds which, in reality, created this reservoir of tainted money in the first place, welcoming into it a new trillion dirty dollars every year. They will continue to exploit this capital and make new money from it. We need a different approach.

I propose that getting the money back should be made a priority of a purposeful national policy, and that all the resources at the disposal of the state should be mobilised to that end. The entire export of arms and agricultural products from Russia in 2015 amounted to $3bn, and the profit was no more than a few billion. Getting this stolen capital back is net revenue for the treasury. We are talking here about establishing a sector whose activities will bring the state budget a sum comparable with the income from the export of hydrocarbon natural resources. Faced with Western sanctions, which primarily limit access to the capital markets, these funds could be a key factor in ensuring financial stability, investment and growth of the Russian economy. Repatriating illegally exported capital should become one of the state’s top priorities.

The measures currently being undertaken by the Prosecutor General’s Office are insufficient. Thus, in 2015 only 6bn rubles (less than $100m) were repatriated out of an officially recorded outflow of 28bn. This relates only to recovery of funds stolen as a result of corruption-related crimes. The colossal amounts taken out of the banking and financial system under fraudulent schemes, whose victims are business entities and the citizens of Russia, do not in general even come within the purview of the law enforcement agencies.

The example of Police Colonel Dmitry Zakharchenko is very illuminating, but there are other Zakharchenkos, generals at that, still around. The main problem is that prosecutors act formally, within the framework of existing international legal agreements. International experience shows that considerably better results can be achieved in this area. Take the example of the United States. Over the past 10 years, the US Attorney’s Office, making use of information from their intelligence agencies and the threat of criminal prosecution, has succeeded in persuading some of the world’s leading banks to transfer more than $350bn to the state budget in out-of-court settlements. So why can’t we? Why not produce similar incriminating evidence and get results? There are, separately, questions to be asked of the international companies that have facilitated embezzlement. Either they return that money, or they are declared persona non grata. They all have major business interests in Russia, so I am confident they will find it more expedient to return, if not all, then at least part of the money.

What could that mean in specific cases, for example, that of Bedzhamov? The High Court in London granted a £1.34bn freezing order on Bedzhamov’s assets whom Russian authorities are seeking over one of Russian’s largest-ever bank collapses. Bedzhamov has previously denied all the criminal charges against him in Russia. In the first place, it is time to throw the book at this “principality”, which belongs in an operetta and welcomes the owners of super yachts. The nouveaux riche organise a vanity fair on the sea every year.

For a start, we need to summon to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs the French Ambassador, who represents Monaco’s diplomatic interests in Russia, and hand him a note of protest. Secondly, break off all relations with Monaco and forbid Russian individuals and legal entities to conduct transactions with the principality’s financial institutions, or invest in real estate in the principality.

These techniques can be employed in all similar cases. We need a systemic struggle against the international offshore financial oligarchy. The reservoir of tainted money needs to be drained, and the money thus obtained needs to be used for the development of human potential. This should be one of the leitmotifs of Russian foreign policy, the work of the competent ministries and departments and of the media. Russia has a unique opportunity to turn the tables and shape a new global agenda by instituting its own campaign of international investigations and diplomatic efforts. If we shut down the offshore tax havens and make the financial world transparent and fair, then life for those living in Popovka will be no worse than it is in the villages of Provence.

I believe that is no more than our people deserve.

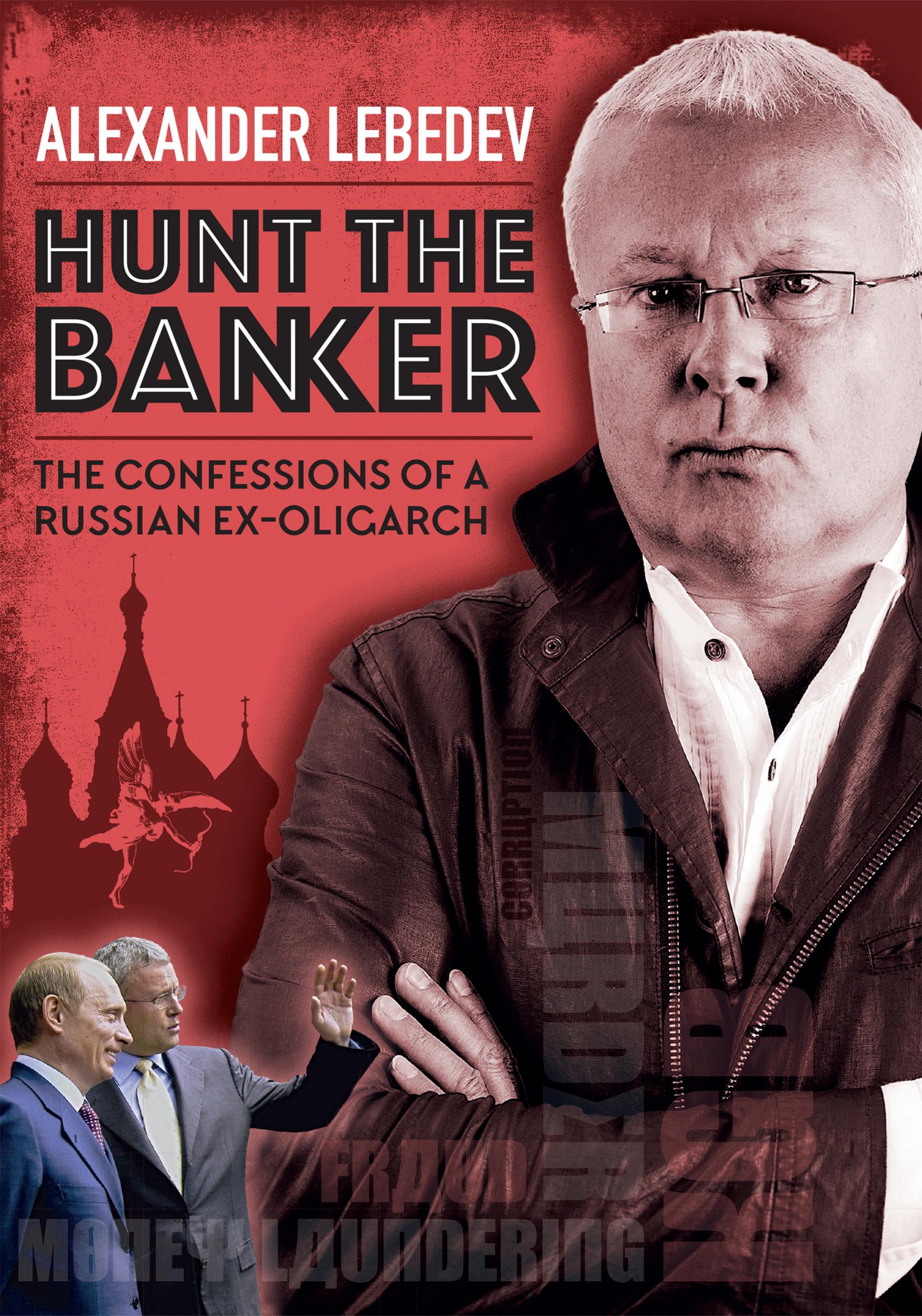

Alexander Lebedev is the father of Evgeny Lebedev, a shareholder in The Independent. His new memoir, ‘Hunt the Banker’, is published by Quiller on 12 September, priced £20. Order from bookshops or www.quillerpublishing.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments