Sam Mendes’s 1917 has been praised for its technique and poetic depiction of the horrors of trench warfare – but is his film original?

The epic war film, which won Best Motion Picture – Drama and Best Director at the Golden Globes earlier this week, has striking similarities to other First World War films, says Geoffrey Macnab

An exhausted German soldier peers out into No Man’s Land. Just a few yards away, he sees a butterfly fluttering in front of a discarded tin. He wriggles forward and stretches out to grab it. As he does so, he breaks cover. A French sniper has spotted him. We are shown the soldier’s hand and the butterfly in big close up. A shot rings out. The hand twitches and then falls still. The soldier is dead. These are the final images of Lewis Milestone’s classic anti-war movie, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930).

It’s striking how similar the reviews of Milestone’s film, adapted from Erich Maria Remarque’s novel, are to those being written now, 90 years later, about Sam Mendes’s 1917 (which won Best Motion Picture – Drama and Best Director at the Golden Globes earlier this week).

“Compelling in its realism, bigness and repulsiveness … the best war picture ever filmed” was Variety’s verdict on All Quiet on the Western Front in 1930.

“Depicting WWI as we’ve never seen it: simultaneously horrific and beautiful, immersive and detached, immediate and impossibly far removed from our own experience” is how Variety’s critic wrote about 1917 a few weeks ago. You could take paragraphs from one of the reviews and slip it into the other without readers noticing the difference.

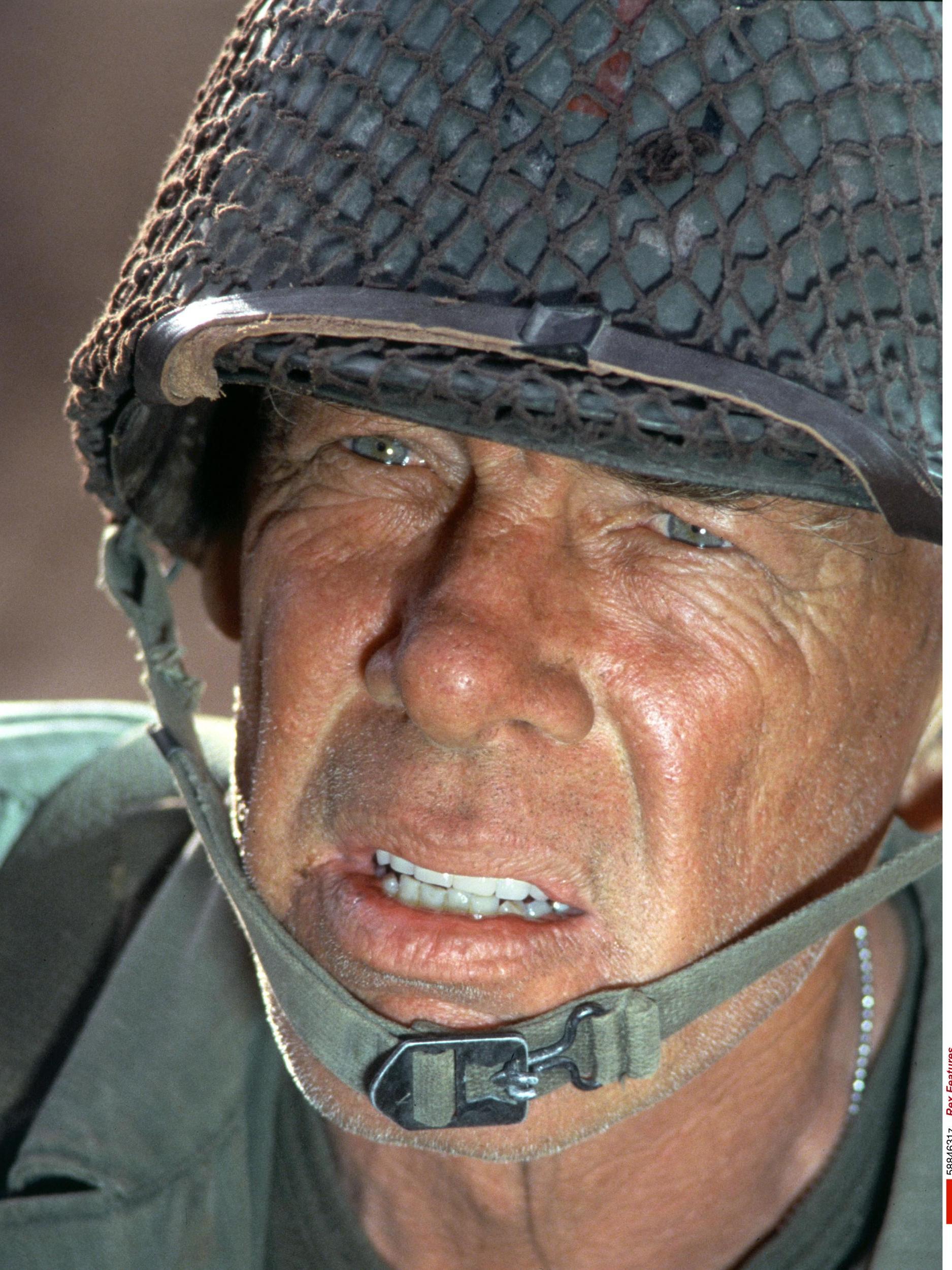

Mendes, like Milestone, has been praised for his formidable technique and poetic depiction of the horrors of trench warfare. 1917 is a formal tour de force for the director and his cinematographer, Roger Deakins, in which we travel through the maze-like trenches and bunkers and across muddy fields with Lance Corporal William Schofield (George MacKay) as he races against the clock to deliver a message that will save the lives of 1,600 fellow soldiers. The filmmakers give us the illusion that the film is unfolding in a single shot and in real time.

Milestone was likewise applauded for his fluid shooting style – considered especially remarkable because he was making his film at the start of the talkie era, using cumbersome, heavy equipment.

1917 is full of flourishes similar to the scene of the dying soldier and the butterfly in Milestone’s movie: moments set in poppy-filled fields or violent chases and fights that take place under incongruously beautiful skies.

The lead actors in the two films are also very similar. Mendes deliberately cast MacKay, an excellent but unsung young actor with a reserved and ingenuous quality, in the leading role. Back in 1930, Milestone, on the advice of his dialogue coach George Cukor, used the then little-known Lew Ayres to star in All Quiet because he was impressed by Ayres’ “self-possessed dignity”.

1917 is a fine film that may add Oscars to its Golden Globes but, for all the boldness of its storytelling style, it suffers from a wearisome sense of deja vu. The First World War has inspired so many films, artworks, memoirs, plays, poems, novels and even sitcoms and video games that it defies original treatment. Anyone making a film set in the trenches now has over a century of material to draw on – and that’s largely the problem.

Even the rodents in 1917 seem familiar. At one point, Schofield and his companion, Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) roam through the quarters which the German army (the dreaded “Hun”) have abandoned hours before. They see an enormous rat. In his book, The Great War and Modern Memory, historian Paul Fussell wrote about how frequently rats have turned up in wartime stories and anecdotes, “big and black, with wet, muddy hair”, feeding on both human corpses and those of dead horses. The rats were so fierce and with such a voracious appetite that they would eat the cats brought in to the trenches to exterminate them. No self-respecting First World War movie is complete without at least a fleeting glimpse of one of these creatures.

That eerie atmosphere, evoked so expertly by Mendes in the scenes of the two NCOs wandering behind enemy lines, is strangely reminiscent of scenes early on in Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One (1980) in which a horse runs across a misty battlefield and an American soldier (played by Lee Marvin) kills a German after the Armistice has been signed. (An act of war thus becomes a murder.)

Thanks to their craftsmanship, attention to detail and the help provided by digital VFX, contemporary filmmakers can achieve astonishing feats when depicting the horror of the trenches. Subjective and immersive camerawork will make audiences feel that they are there, in the midst of the chaos and carnage, seeing it from their own point of view. Giving their films an emotional authenticity is often far more of a struggle for these filmmakers. You can research war exhaustively and you can draw on stories and information given to you by those who were on the front lines (Mendes drew inspiration from tales told to him by his grandfather Alfie), but that doesn’t mean you know what it was really like.

The distinguished military historian John Keegan put it nicely in the introduction to his 1976 book, The Face of Battle. “I have seen a good deal of other, earlier battles of this century on newsreel, some of it convincingly authentic, as well as much dramatised feature films and countless static images of battle,” Keegan wrote. “But I have never been in a battle. And I grow increasingly convinced that I have very little idea of what a battle can be like.”

Showing what battle is really like is what most war movies aspire to do, but it is almost always beyond them.

One secret that filmmakers are wary to disclose is that what purport to be anti-war movies are also often boys’ own adventures. It’s striking how many reviewers have likened 1917 to fairground rides or first-person shooter games.

“Amazingly audacious … a ghost train ride into a day-lit house of horror”, enthused The Guardian about 1917. Others likened it to a “ghoulish video game” while The Independent talked in its review about contemporary directors’ obsession with turning war films into a “pseudo-virtual-reality experience”.

Mendes’s grandfather observed how the stories of his “hair-raising” adventures at the front “enthralled” his relatives, while Mendes talked to Screen International of his desire to make “a non-franchise event movie” that could play on the very biggest screens. In other words, his intention is to entertain audiences, not to shock them.

Celebrated American B-movie director Fuller once observed that the only way filmmakers could convey the reality of war to their audience would be for someone to take occasional potshots at spectators from behind the screen during the battle scenes.

Fuller was a former soldier who had seen war at first hand. His own war films were made on relatively small budgets, without armies of extras or sophisticated special effects, but he tried to convey how war traumatised those who experienced it. He also acknowledged the impossibility of his own task.

“One of the cruxes of the war, of course, is the collision between events and the language available – or thought appropriate to describe them,” Fussell wrote in The Great War and Modern Memory.

The idea that language is inadequate to describe the horrors of the First World War is itself a cliche. Painters, writers and filmmakers have queued up to describe the war as “indescribable”, but that hasn’t stopped them from trying to represent it in their work. The basic formula in First World War movies has remained pretty much the same from the era of Lewis Milestone to the present day. Directors want to show the squalor and destruction. There will generally be barbed wire, mud, skulls and vermin. However, in the grimmest moments, we will see flickers of humanity and decency. The Scots will play their bagpipes, the Germans might sing opera arias (as in 2005’s Joyeux Noel). During truces, soldiers will shake hands across enemy lines and even play football together.

Filmmakers relish the chance to let the camera loose in the trenches. Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) is full of travelling shots in which we see officers prowling through the maze-like encampments where soldiers are either preparing for battle or recovering from it. Individual trenches are given the names of famous British streets. There is always a tension between the formal, exaggeratedly civilised behaviour of officers and their soldiers in the trenches, and the death and suffering awaiting them the moment they go “over the top”.

Some filmmakers have tried to take the perspective of the victims. Dalton Trumbo’s experimental Johnny Got His Gun (1971), adapted from his own 1939 novel, features a protagonist (played by Timothy Bottoms) who has lost his arms, legs, ears and mouth in the First World War and who describes himself as “a piece of meat that keeps on living”. The film received very hostile reviews and wasn’t a box-office success. François Dupeyron’s The Officers’ Ward (2002), about French soldiers disfigured by injuries sustained in the First World War, rejected by their wives and treated as pariahs, was respectfully received but did only modest business. Like Johnny Got His Gun, it was considered too downbeat and depressing

In 1917, Mendes isn’t (just) trying to rub his audiences’ faces in the suffering and squalor of the war. This is a rousing, brilliantly made epic about a soldier’s attempts to save the lives of his comrades. It combines brutality and lyricism. The caveat, though, is that we have seen and heard it all before. There is little in it that hasn’t already been touched on in the countless other stories about the war to end all wars that have been told on screen since Lew Ayres reached for the butterfly all those years ago.

‘1917’ is out today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments