The Human Factor exhibition review: Investigating the body politic at the Hayward Gallery

A new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery exploring the development of figurative sculpture over the past 25 years shocks, repels and amuses in equal measure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

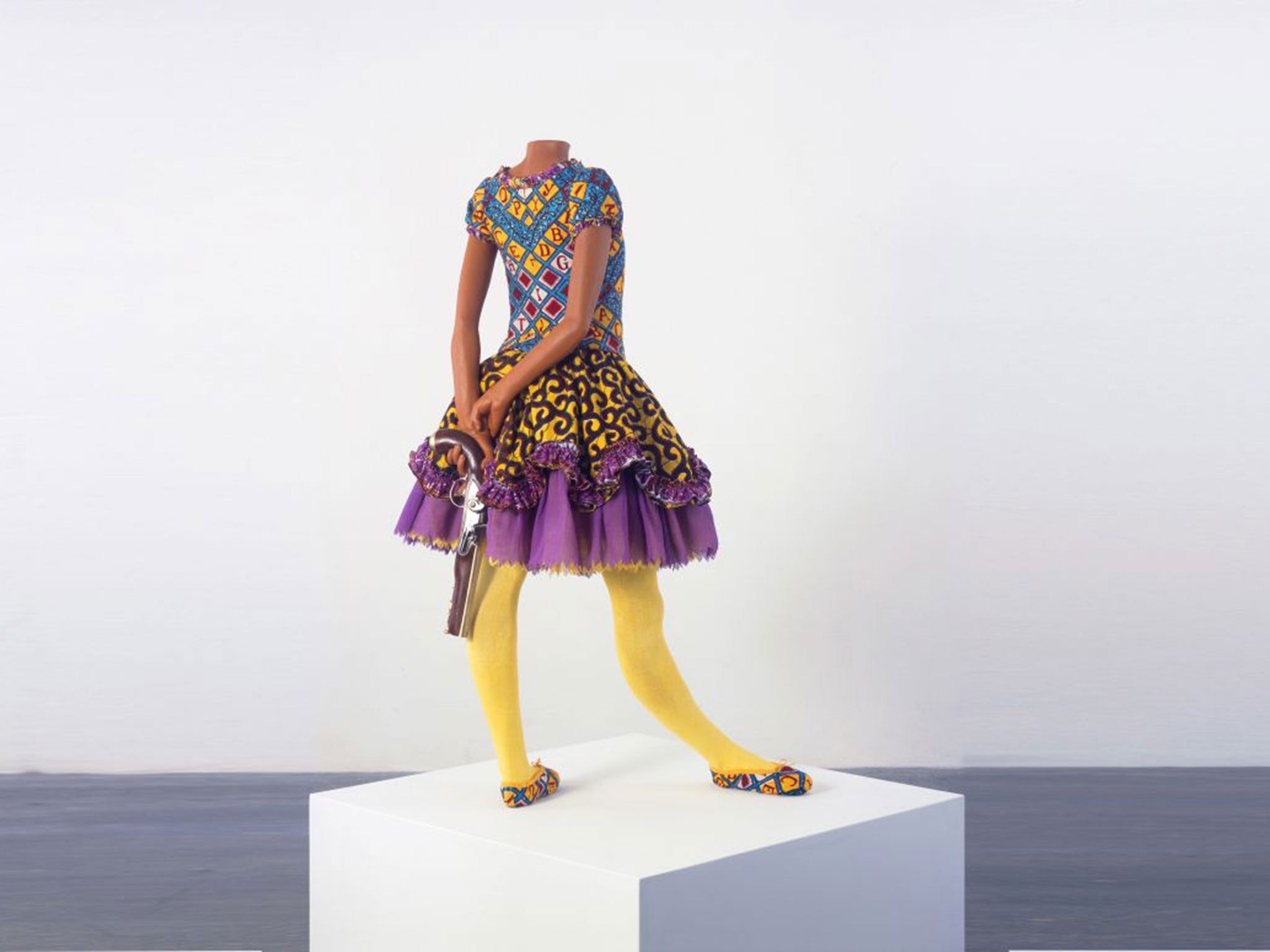

Your support makes all the difference.A young ballerina stands primly with her hands behind her back, pointing her toes. She is a headless mannequin, a sculpture by the artist Yinka Shonibare. She seems docile, but she is not. When you walk around her, you find that she is hiding a huge gun behind her back.

The work is alarming, darkly funny, mysterious – we do not know what has inspired her murderous rage. A clue lies in the bright, African-print of her tutu – one of Shonibare’s themes is colonialism and his ballerina is possibly cast as a revolutionary. Her combination of girlishness and calculated violence is compelling, and sets the tone for The Human Factor, a new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, which explores figurative sculpture over the past 25 years.

This ancient medium, which once celebrated the heroic ideal of Greek gods and athletes, is reimagined by 25 international artists. They explore both the roots of the medium and its place in the contemporary world, which inevitably means themes of alienation, consumerism and despair. Overall, the exhibition is a joy with trompe-l’oeil shocks that make you think, rather than roll your eyes. I enjoyed it a lot.

Shonibare’s work is modelled on Edgar Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1880-1), a wax sculpture of a ballerina, which the artist adorned with human hair. This was shocking at the time – it combined the viscerally real with the blatantly fake. Many of these works similarly play on our sense of the uncanny.

The curators have included another work based on Degas’ ballerina – Ryan Gander’s I don’t blame you, or When we made love you used to cry and I love you like the stars above and I’ll love you ‘till I die (2008). This is a ridiculously long-winded title; the work itself is succinct. At first glance, there appears to be nothing but an empty white plinth. Walking around it, however, you discover a small, doll-size cast bronze sculpture of a ballerina, her tutu removed, her pumps still on, leaning against the plinth and smoking a cigarette.

This made me laugh – the suggestion is that Degas’ original has spent nearly 150 years standing primly on display and deserves a well-earned fag break. She is taking some time out from being an object and enjoying a moment of private contemplation. She is hiding from the viewer – the work is absurdist though makes a point.

The solidity and grandeur of sculpture has historically been used to immortalise the values of a culture – what can sculpture immortalise now? Where once statues of Aphrodite, goddess of love, celebrated the maternal, nurturing, sumptuous qualities of female flesh, today the most common “sculpture” of the female figure that we are likely to see is the mannequin in the high-street shop window.

The female form is bound up with consumerism and desire in the contemporary world; it is most often used to sell us something that we are supposed to want. The spectre of the synthetic female nude is explored most strikingly by Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn, whose two installations are some of the most powerful works in the exhibition.

4 Women (2008) consists of four naked mannequins in a glass showcase, their long fake black hair hanging down, their faces scornful and vacant. The numbers one to four are taped to their heads, which gives the impression of a beauty pageant, albeit nightmarish.

The work is made extraordinary by two things: the first is a viscous, bubbling royal-blue substance in which the mannequins are submerged up to their knees. It appears to be made of the kind of foam found in cheap sofas. The blue stuff crawls up their bodies and seems to emanate out of each of their right nipples. This is a horrible twist on the classical ideal of the nurturing mother. It provokes disgust.

The second detail is the series of four photographs taped to the front of the showcase; each is similarly numbered one to four, which suggests a correlation to the mannequins. Each shows a bloodied corpse, seemingly the result of warfare, sourced by Hirschhorn from the internet.

While the blue substance seems to be a visual manifestation of psychosis, a kind of horror of the mind, the photographs show real violence. The link between the two is oblique, but there is a logic. The work evokes the disparate though connected parts of modern capitalism: shopping, war, pornography. It is poetic and challenging.

My main criticism of this exhibition is that it relies too heavily on the kind of critique of modernity (or post-post-modernity) that Hirschhorn does very well. Elsewhere, the theme shades into kitsch irony that just seems empty. The paralysed, alienated, hyper-real figure – often a mannequin – recurs too often.

There is John Miller’s coltish boy mannequin in a diamond-patterned playsuit, his foot – inexplicably – stuck in a pile of manure; Frank Benson’s silver spray-painted life-like nude male, as well as his female couture model in 1980s sunglasses. All of these figures look as though they belong in Studio 54; there is an ambience of nostalgic disco.

Like the ripped and coiffed poseurs of the ancient world, these sculptures often appear homoerotic. The classical ideal of beauty sought harmony in the perfect proportions of the human form, and these express our modern equivalent – the aspirational glamour of hipsterdom, wan thinness and youth. I’m not sure if they are critiquing modern consumerism, or simply celebrating it – which is no doubt the point.

The king of such wilfully lurid 1980s kitsch is Jeff Koons. His large sculpture, Bear and Policeman (1988), is displayed here: it is intended to look like a cheap trinket, but in fact was made out of polychromed wood, using a process which originated with sculptors of religious works in medieval Europe. Koons has always delighted in sacrilege.

The sculpture consists of a policeman staring up – adoringly? – into the eyes of a giant cartoon bear, who has seized the policeman’s whistle and seems about to blow it. Koons has described the work – one of his Banality series – as depicting “a man being sexually toyed with”. The work is extravagantly weird, uncomfortable, clammy. I usually hate Koons’ work, but it is strangely affecting.

Far more interesting, though, is the dialogue that the curators have staged between the works of Rebecca Warren and Paul McCarthy. A small room is filled with four of Warren’s sculptures: each is a mammoth and monstrous rendition of the female body, headless and bulging with nipples that protrude like weapons. The aggressive sexuality of these near-abstract figures is reinforced by their rough, clay-like appearance. In fact, many are cast in bronze. They seem only partly formed, bearing the rough marks of the sculptor’s hands.

If the sculptor had been a man, these works would seem misogynistic. The fact they were made by a woman determines much of their meaning and resonance for me. They become questions, rather than reiterations of the age-old dynamic between male artist and female nude subject.

By contrast, McCarthy’s three platinum silicone sculptures of the actress Elyse Popper are eerily realistic – scientific in their rigor. She is shown in slightly different poses, sitting naked on top of what may be a gynaecologist’s table; her legs are open and her flesh is delineated through special effects. The blue veins beneath her skin are visible; so too are the traces of her recently removed nail-polish, and, most strikingly, the anatomical detail of her vagina.

She appears serene, perhaps waiting. She is beautiful and somehow does not seem objectified, despite the merciless precision with which she has been made. There is grace in her stillness, which either points to the total submission of the muse under the gaze of the artist, or a frankness which is progressive. Here the human body is shown honestly – which of course is an illusion.

‘The Human Factor’, Hayward Gallery, London SE1 (020 7960 4200; southbankcentre.co.uk) 17 June to 7 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments