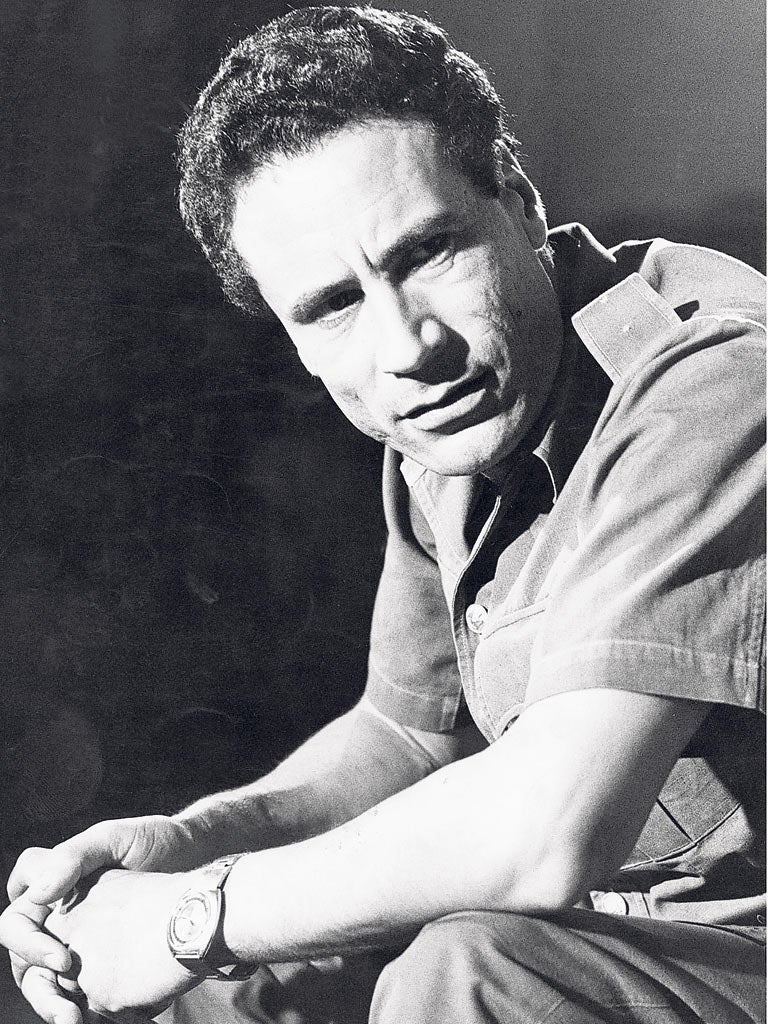

Muammar Gaddafi: Leader of Libya who made his country an international pariah

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For most of his life Muammar Gaddafi was the enfant terrible of world politics. He espoused every loony cause presented to him, was an almost open backer of terrorism and terrorists, and annoyed his neighbours either by proposing impractical unions with them, or occasionally going to war. He saw himself as a world statesman, but was generally regarded as a joke, a nuisance or a lunatic.

Gaddafi's saving grace, which allowed him to hold on to power for so long, was that he was personally ascetic, and apart from such foibles as a squad of female bodyguards or a Bedouin tent set up in his underground bunker, never went in for the trappings of power. Ruling a country of 15 million with a huge and steady oil income, he made sure the benefits went to the people, not to himself or his associates. Libyans had houses, an excellent health service, clean streets and plenty of things to buy, even when sanctions against him were in force. They also lived with an army of informers and ruthless domestic intelligence services which were swift to act against any signs of dissidence.

Gaddafi remained a joke to the international community, with a ripple of laughter greeting him whenever he rose to speak at a conference, his cape swirling about him like a caricature of a Hollywood star portraying a Middle Eastern despot. In his latter years, what he said was often sensible, but he had so squandered his reputation in his earlier years that no one took him seriously. Everyone remembered the early judgement of Mohammed Heikal, the authoritative commentator, that he was shockingly pure and amazingly naive.

They remembered, too, the abortive unions with Egypt, Syria, or Tunisia, and paid little attention to his analyses of world affairs or his recommendations for international action. In the end, he was seen as a man who had over-reached himself, humbled by the Americans. The final handing-over of the Libyan Lockerbie suspects seemed to signal that he had retired from the one sector where he had made a name for himself and might have continued to act: in fomenting terrorism.

Gaddafi burst on to the scene in 1969 as the leader of the young officers' coup against King Idris, an irresolute and usually absent ruler who was trying to go against the strain of Arab opinion by allowing America and Britain to retain bases in his country, and by failing to take a stand against Israel.

Gaddafi, it seemed, had been preparing his coup almost since he was a child, inspired by the speeches of Gamal Abdel Nasser, which he listened to on the radio in his father's family tent in the desert near Sirte. Gaddafi's family was Berber-Bedouin, and though his father eventually prospered as a merchant, in his early years they were extremely poor. He was able to go to school and to college in Benghazi, then joined the army as a way toward power. Among those training him were British officers who found him a natural leader, but also one unwilling to abide by the rules or follow orders. He spent six months on a course in England, a time he hated.

Gaddafi took the words of Nasser at face value, with no appreciation of the subtleties needed by a politician, or of the trimming, wheeling and dealing required. His policies, he proclaimed, were based on the principles of Islam, Arab nationalism, and democracy, with a nod towards African nationalism. The institutions of State were discarded, and instead, power was to be exercised through peoples' assemblies and committees, though ultimate control was kept carefully in Gaddafi's own hands – few of his early associates lasted as long as he did. The Arab Socialist Union was declared to be the only legal political party, and the Revolutionary Command Council the ultimate authority.

Soon after assuming power, Gaddafi began his drive towards the unity of the Arab nation, to begin with the amalgamation of his own country with his neighbours. In 1972 Egypt, Syria and Libya did declare a federation, which Gaddafi certainly took seriously, though to Anwar Sadat in Egypt and Hafez Assad in Syria it was no more than a palliative designed to keep their impetuous and annoying neighbour quiet while they prepared for war with Israel. The union was never implemented. Similar attempts at mergers with Egypt, Syria, Chad, Morocco and Tunisia were no more successful, which came as no surprise to anyone except Gaddafi, as he had intervened by military or clandestine means in all of those countries, occupying the Aouzou Strip of Chad in 1973, and in 1979 and 1980 supporting the Polisario Front in its war with Morocco over Spanish Sahara.

It was in this middle period of his rule that Gaddafi earned his reputation as a serious troublemaker with his support for "revolutionary" movements around the world, from the IRA to the PLO to dissident groups working against the Palestinian cause. His avowed devotion to Islam seemed strained too; it was while on a visit to Libya that the Imam Musa al-Sadr, the leading Shi'ite leader from southern Lebanon, was murdered, with efforts by the authorities to conceal the crime. The cause was a dispute over money he had been given by Gaddafi to finance opposition to the Israelis in south Lebanon, and the Imam's supposed lack of action.

Gaddafi was married shortly before seizing power in 1969 to Fathia, the daughter of a senior officer in the King's Army, but after only a year divorced to marry Safiya, with whom he had seven children. This did not stop his phil-andering; when newspapers wanted to be sure of securing an interview they sent their prettiest female correspondents, and were rarely disappointed. Reporters usually spent more time fending off Gaddafi than asking questions. He was also known for his warm relations with his female bodyguards, chosen more for looks than weapons proficiency.

None of this distracted Gaddafi from his terrorist campaigns, most aimed at his own dissidents, or Arabs from other countries, rather than the US, the constant target of his rhetoric. It was this which brought him his biggest setback, with the US bombing of targets in Benghazi and Tripoli in 1986, ostensibly in retaliation for the terrorist bombing of a Berlin nightclub in which a US serviceman was killed. Again, in 1989, US forces provoked a clash with Libya in which two Libyan jets were shot down.

From then on, Gaddafi appeared to try hard to avoid conflict with the US, though he was blamed for the sabotage of the Pan Am airliner over Scotland in 1988 and the French airliner over West Africa in 1989, with 441 people killed in the incidents. Sanctions were imposed in 1992 to try to persuade him to hand over two Libyans implicated in the bombings. It was not until 1999 that the sanctions were lifted, with the two suspects handed over to be tried by a Scottish court sitting in the Netherlands.

Throughout this period of supposed international isolation, however, Libyan oil production had continued, and ensured continued relative prosperity, with a number of major new developments. Chief of these was the "Great Man-Made River", a huge pipeline to carry water from underground sources in the Sahara to the densely populated coastal regions. This again raised tension with Egypt, who feared that the work might have an effect on the Nile. As it was, relations with the country which had once inspired Gaddafi had been bad since Libya opposed Egypt's decision to make peace with Israel.

Libya under Gaddafi was known as a "Jamahiriya", a made-up word meaning a state run by the people. In fact, Libya was a military despotism, with powerful security forces to see that the military stayed in line; there were several mutinies ruthlessly suppressed. Gaddafi also survived assassination attempts, and the US bombing of his headquarters in which his daughter was killed.

From the wild man of the Arab world, as damaging to his fellow rulers as to their enemies, he became a chastened figure, brought to heel by the ruthless application of superior force. To all but his own people, he was little more than a buffoon. And to most Libyans he was someone to be avoided, and to be watched in amazement from a distance.

But in 2000 there began a gradual rapprochement with the West, paradoxically, if indirectly, arising from the most signal act of mass murder for which Gaddafi had long been blamed – the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am jet over Lockerbie in Scotland, which killed 270 people. After negotiations with various Western secret service officials, including Sir Mark Allen of MI6, and two years after the conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the bombing, in August 2003 Libya formally accepted responsibility for the "actions of its officials" and agreed to pay compensation of up to $2.7bn. In the same year, in a move that was greeted as a direct consequence of the Iraq war, but which may rather have been a continuation of Gaddafi's earlier efforts to rebuild relations with the West, he announced that he had a weapons of mass destruction programme – including nuclear and chemical – but that he was willing to have them inspected and dismantled.

The earliest high-profile reconciliation came with the trip made by the then British Prime Minister Tony Blair in March 2004, who visited Gaddafi and extended what Mr Blair called "the hand of friendship". The image of Blair's remarkable five-second handshake with Gaddafi, symbolising the beginning of the end of the Libyan leader's pariah status, went around the world. The defence of the rapprochement was that it met a vital global need, ensuring an end to the promotion of terrorism and an unacceptable weapons programme operated by a dangerous and unpredictable regime, coupled with an opportunity for him and the oil industry to benefit from further extraction of Libya's vast reserves.

For the critics, the rapprochement reflected naked Western commercial interests – especially, but not only, those of the oil multinationals – to which long-held principles of foreign policy had been sacrificed. Either way, a complex series of quid pro quos were applied by Gaddafi and the West in the coming years. In 2007 five Bulgarian nurses eccentrically accused of infecting Libyan children with Aids were released; al-Megrahi was granted another appeal; most of the remaining 20 per cent of the compensation fund was paid; and George W Bush restored the regime's immunity from terror-related lawsuits.

These bargains would come under greater retrospective scrutiny than they did then, once the popular uprising against the regime, and in particular against Gaddafi himself, erupted in February 2011. Even at the time, however, there were grave doubts, not least in Washington, about the Scottish government's decision to release Megrahi on health grounds in 2009, only to see him return to Tripoli to a hero's welcome – doubts reinforced when the UK Foreign Office was charged with having done "all it could" to secure the convicted bomber's release.

The agonising in hindsight was all too easy to understand. For in response to the uprising, Gaddafi seemed to return to a replica of his old self: not only autocratic, but dangerous, violent and self-obsessed. He would fight "to the last drop of blood"; his loyalists would be armed to "crush the enemy" – which it was becoming clear, was a majority of the population. Helicopter gunships attacked protesters; thugs were armed and blood-curdling threats carried out. But it was not enough to save Gaddafi; finally his exercise of power over more than four decades, and along with it his own life, was at an end.

John Bulloch

John Bulloch died in November 2010; this obituary has been updated by Donald Macintyre.

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, politician: born Sirte, Libya 7 June 1942; Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution of Libya 1969-; married firstly Fathia Khaled (divorced; one son), secondly Safiya Farkas (three sons, and one son adopted, two sons deceased, one daughter, and one daughter adopted); died Sirte 20 October 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments