Mowbray happy and at home back in Boro

The Middlesbrough manager takes Martin Hardy through the details of his quiet Riverside revolution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tony Mowbray is smiling. "Look," he says. "If we've got to do a picture, I don't want one of me looking all moody. You know, where I'm all serious, and deep in thought."

Mowbray turns to our photographer, and his face drops (not literally). "Like this, when I'm talking, so I look all gloomy."

Message imparted, the manager of Middlesbrough walks from behind the reception desk at the club's Hurworth training ground. "Come here," he says, and we walk through a door to where the usual media suite has been turned into a classroom. "Have a look at that."

Twelve children in red Middlesbrough training tops are sat tapping away at computers. "It's part of the EPPP scheme, they're 11 years old."

"All right, lads?" he asks. Nervously they turn from their monitors. "Come on the Boro!" he shouts.

"Imagine that," he adds. "Coming into your club when you're 11 and effectively being a pro footballer. They train with us, they get their lessons, they put their boots back on, go out and play and then we feed them. It must be great, eh?"

Nearly two years in, Middles-brough are starting to feel like what they have always been to Tony Mowbray. His club.

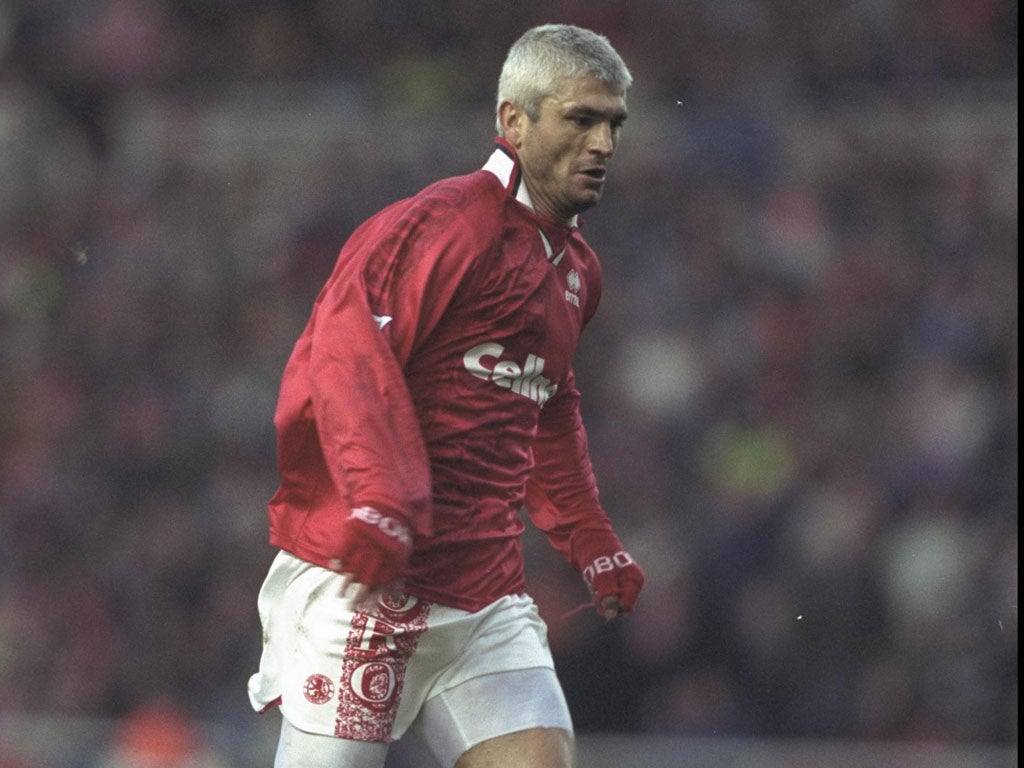

He watched them with his dad. Stood on the Holgate End with his mates. Captained the team when he was 22. Stood as its heartbeat in the middle of defence for 10 seasons and on 26 October 2010, when there was a chance they could again fall into the third tier of English football, got the call that it was time to come home. There were 500,000 (pounds in compensation from Celtic) reasons to say no. There was one to follow his heart.

"People I knew who had been here for 20 years, people who were here before I left as a player, were losing their jobs," he adds. "I found that very hard. The reality was it had to happen, as far as I can see. [The chairman] Steve Gibson has been putting money into the football club and we are still striving to balance the books."

The Prozone figures are fresh on Mowbray's desk. Passing statistics are important. Middlesbrough are top, averaging 483 in their four games (won two, lost two).

That is impressive, over 100 per game more than anyone in the division. It adds to a deep sense of optimism that Middlesbrough are back, moving in the right direction after a quietly traumatic period. (Finishing 12th in the table in Mowbray's first season and seventh last.) "It is evidence of a philosophy we are trying to bring in looking after the ball. Within that we have to keep the ball out of our net, though! And we have to have end product and win matches but I've always believed the best teams generally have the ball."

Twelve new players arrived in the summer, among them Jonathan Woodgate and Grant Leadbitter. Expectations are rising. The stadium remains half-full but Mowbray, a modest man, talks of "when" Middlesbrough are back in the Premier League, and he has a quiet confidence that this season will see them in the mix. His family have settled back home. He is 10 minutes from his mam and his sister. His children are settled in schools. It all helps. "The chairman does it for the town and so do I. It is not about egos. I do it for the town and the football club I watched as a boy with my dad on the terraces. He wants the fans to be proud when they go to the pub on a Saturday night and so do I."

He gets up and walks over towards his magnetic tactics board. "Come over here," he adds. "There you go, there's my players, on the wall, you'll get an insight into my team for Saturday here, but look, I'll study the videos, and I'll check the stats, I'll talk to my coaches, the door to their office [which links to his] is always open, we'll chat. I might move him there, or if someone's coming back from injury, like he is, I might consider him."

At that point he looks his happiest; thinking about football, his team, his players, deep in one of his million thoughts. In the corner of the room, which is fairly sparse, hidden behind a sofa is a small corner table, about a foot high. On it, crammed together, sit 15 trophies from his 10 years as a manager.

"Yeah, when we moved I was going to put them back in the loft, but then I thought I'd put them in the corner so if I've had a bad result I can come into my office and think, 'Yeah, I'm not that bad a manager.' But they're not mine. They're for every team I've managed. They're for the staff and the players."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments