The art of seduction

When Elaine Sciolino arrived in Paris as a 'New York' correspondent, she quickly learnt how to play the French national sport - seduction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first time my hand was kissed à la française was in the Elysée Palace. The one doing the kissing was the president of France, Jacques Chirac. It was 2002, the Bush administration was moving towards war with Iraq, and I had just become the Paris bureau chief for The New York Times. Chirac was announcing a French-led strategy to avoid war. He welcomed me with a baisemain, a kiss of the hand.

Chirac reached for my right hand and cradled it as if it were a piece of porcelain. He raised it to the level of his chest, bent over to meet it halfway, and inhaled, as if to savour its scent. Lips made contact with skin. It was not an act of passion. Still, it was unsettling. Part of me found it charming and flattering. But in an era when women work so hard to be taken seriously, I also was vaguely uncomfortable that Chirac was adding a personal dimension to a professional encounter. Catherine Colonna, who was Chirac's spokeswoman, told me later that he did not adhere to proper form. "He was a great hand kisser, but I was not satisfied that his baisemains were strictly executed according to the rules..." she said. "The kiss is supposed to hover in the air, never land on the skin." If Chirac knew this, he was not letting it get in the way of a tactic that was working for him.

The power kiss of the president was one of my first lessons in understanding the importance of seduction in France. Over time, I became aware of its force and pervasiveness. I saw it in the disconcertingly intimate eye contact of a diplomat discussing dense policy initiatives; the exaggerated, courtly politeness of my elderly neighbour; the flirtatiousness of a female friend that oozed like honey at dinner parties. Eventually, I learnt to expect it. In English, "seduce" has a negative and exclusively sexual feel; in French, the meaning is broader. The French use "seduce" where the British and Americans might use "charm" or "engage" or "entertain". Seduction in France does not always involve body contact.

A grand séducteur is not necessarily a man who seduces others into making love. (Neither is he usually a man in the mould of Dominique Strauss-Kahn.) He might be gifted at caressing with words, at drawing people close with a look, at forging alliances with flawless logic. The target of seduction – male or female – may experience the process as a shower of charm or a magnetic pull.

How to play the game

"Seduction" in France encompasses a grand mosaic of meanings. What is constant is the intent: to attract or influence, to win over, even if just in fun. To play, several weapons need to be mastered. The first is le regard, "the look", the electric charge between two people when their eyes lock and there is an immediate understanding that a bond has been created. The concept is a classic component of French seduction, rooted in antiquity. I decided to learn more about le regard. I knew in advance I would never learn how to do it properly myself, as I am hopelessly shortsighted, which means that my eyeballs get reduced to the size of peas behind my glasses. But as a journalist, I'm a trained observer. In real life a sexually tinged regard may also be used to disarm. On a visit to Strasbourg in April 2009, Carla Bruni found herself in front of a swarm of photographers calling her name. She decided to give herself to one of them. For five minutes she posed, looking only at him, ignoring all the others. He was gobsmacked. Le regard is not done with an open, wide, American-style grin but mysteriously and deeply, with the eyes. Never with a wink. "French women don't wink," one French woman told me. "It disfigures your face."

Words are the second weapon. Verbal sparring is crucial to French seduction, and conversation is often less a means of giving or receiving information than a languorous mutual caress. When words are used as a tool of sexual seduction, indirection and discretion may work best. The frontal approach can be considered brutal and vulgar. Private coaches can be hired in Paris to teach professional women how to rid their voices of chirpiness and men how to cultivate lower tones.

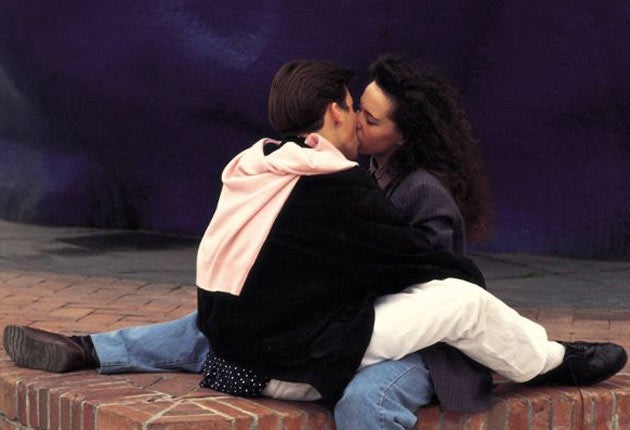

The kiss, the next natural weapon, is subject to its own rules. The most social kiss is la bise, the kiss on each cheek. I always have considered it a straightforward ritual. But Florence Coupry and Sanae Lemoine, my researchers, ganged up on me and explained how cheek-kissing could come with extraordinary power. "You can give la bise to say 'hi' to people you know, and there would be nothing special about it," said Florence. "But... let's say that one day... I also kiss someone I've been dreaming about... I'm so close to him for a second... and it will be absolutely delicious and maybe troubling. Maybe only I know what's happening... Or maybe he guesses it and then what could happen?" Sanae chimed in: "Sometimes his lips will touch your cheek, or he'll try to come as close as he can to your lips and touch your waist lightly with his hand. La bise allows you to get intimate."

Finally, the deal must be clinched. Christophe, a French man in his mid-twenties who is both clever and handsome, has a strategy. "I always play by the rule of the three Cs – climat, calembour, contact," he confessed. Climat is context. "You want to establish a specific atmosphere, which can be somehow magical," he said. "You can transform a random situation into an atmosphere where you feel you are going to kiss each other." Calembour, which literally means "pun", comes next. "You need to make her laugh," he said. "But it has to be subtle." The clincher comes with contact. "At the fateful moment, you manage to establish physical contact," he said. "Not a big slap on the back. But... you touch her arm. Or crossing the street, you take her arm. This is a very strong signal. And if she does not reject it, you can almost be sure you can at least kiss her."

Be prepared at all times

It took years before I fully understood French attitudes to public space. I found it both sexist and offensive that strange men felt entitled to comment on what I wore or how I looked. Yet in Paris, women and men are supposed to please each other on the street. You never walk alone but are in a perpetual visual conversation with others, even perfect strangers.

My own style is relaxed. Take the Saturday afternoon I was making cookies with my daughters and ran out of butter. Dusted with flour, still in my jogging clothes from a morning run, I dashed out to the shop. But this was the Rue du Bac, a chic place to see and be seen on Saturdays. I heard my name called and turned to face Gérard Araud, a senior Foreign Ministry official. He was wearing pressed jeans, a soft-as-butter leather jacket, caramel-coloured tie shoes, and an amused look. In his hand was a small shopping bag containing his purchase of the morning. Gérard invited me to take a coffee with him. We sat outdoors at a café on the corner of the Rue de Varenne. I should have known better and invited him into my kitchen. This was one of the premier people-watching intersections in all of Paris. I was inappropriately dressed.

The Swedish ambassador and his wife rode up on their bikes and stopped to say hello. Both were in tailored tweed blazers, slim pants, and expensive loafers. Then Robert M Kimmitt, the American deputy treasury secretary at the time, who happened to be visiting Paris, walked by. He accepted Gérard's invitation to join us. "I see that Paris hasn't done much for your style," Kimmitt joked. "At least I'm wearing black," I replied. When he left, Gérard made what he considered an important point with as much seriousness as if he were delivering a diplomatic démarche to a recalcitrant ally. "The Rue du Bac is not the Upper West Side," he said. "All right, all right," I conceded. I knew the rules: jogging clothes (shoes included) are to be removed as soon as one's exercise is over. Then I got a bit defensive. "This is my neighbourhood," I said. "I belong here. So I can dress however I want!" "You can," he said, with the sangfroid that makes him such a good diplomat. "But you shouldn't."

Seduction and politics

The spring of 2008 was a particularly uneasy moment in France. Nicolas Sarkozy had been president for a year, and a recent poll had determined that the French people considered him the worst president in the history of the Fifth Republic. His failure to deliver quickly on a campaign promise to revitalise the economy was perceived as a betrayal so profound that a phenomenon called "Sarkophobia" had developed. Around this time I read a new book written by a 34-year-old speechwriter at the Foreign Ministry named Pierre-Louis Colin. In it, he laid out his "high mission": to combat a "righteous" Anglo-Saxon-dominated world. The book was not about France's new projection of power in the world under Sarkozy, but dealt with a subject just as important for France. It was a guide to finding the prettiest women in Paris.

"The greatest marvels of Paris are not in the Louvre," Colin wrote. "They are in the streets and the gardens, in the cafés and in the boutiques. The greatest marvels of Paris are the hundreds of thousands of women whose smiles, whose cleavages, whose legs bring incessant happiness to those who take promenades." The book classified the neighbourhoods of Paris according to their women. Just as every region of France had a gastronomic identity, Colin said, every neighbourhood of Paris had its "feminine specialty". Ménilmontant in the north-east corner was loaded with "perfectly shameless cleavages – radiant breasts often uncluttered by a bra". The area around the Madeleine was the place to find "sublime legs". Colin put women between the ages of 40 and 60 into the "saucy maturity" category.

The book was patently sexist. It offered tips on how to observe au pairs and young mothers without their noticing and advised going out in rainstorms to catch women in wet, clingy clothing. It could never have been published in the United States. But in France it barely raised an eyebrow, and Colin obviously had fun writing it. The mild reaction to a foreign policy official's politically incorrect book tells you something about the country's priorities. The unabashed pursuit of sensual pleasure is integral to French life. Sexual interest and sexual vigour are positive values, especially for men, and flaunting them in a lighthearted way is perfectly acceptable. It's all part of enjoying the seductive game.

The sangfroid about Colin's book made for a striking juxtaposition with the hostility toward France's president. To be sure, the flabby economy was one reason Sarkozy was doing so badly at the time; another was that he hadn't yet mastered the art of political or personal seduction. But he was trying. Sarkozy's second wife, Cécilia, had dumped him after he took office. As president of France, he couldn't bear to be seen as lacking in sex appeal. In the United States, mixing sex and politics is dangerous; in France, this is inevitable.

In the weeks after Cécilia's final departure, Sarkozy had presented himself as lonely and long-suffering, but that had seemed very un-French. Then he had met the super-rich Italian supermodel-turned-pop singer, Carla Bruni, and married her three months later. On the anniversary of his first year in office, Sarkozy and Bruni posed for the cover of Paris Match as if they had been together forever. Sarkozy looked – as he wanted and needed to – both sexy and loved.

Ihad gone off to live in Paris. And it has seduced me. "Every man has two countries, his own and France," says a character in a play by the 19th-century poet and playwright Henri de Bornier. In our years living there, my family and I have tried to make the country our own, even though we know that will never entirely happen. We will never think like the French, never shed our Americanness. Nor do we want to. And like an elusive lover who clings to mystery, France will never completely reveal herself to us. Even now, when I walk around a corner, I anticipate that something pleasurable might happen – just the next act in a process of perpetual seduction. I often find myself swept away without realising how it happened. Not so the French. For them, the daily campaign to win and woo is a familiar game, instinctively played and understood.

This is an adapted extract from La Seduction: How the French Play the Game of Life by Elaine Sciolino (Beautiful Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments