Russian revelation

Russia's history is long and fascinating. Former BBC Moscow Correspondent, Martin Sixsmith reveals his key locations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Novgorod

This beautiful city, 120 miles south of St Petersburg, was the first centre of the Russian lands. In the 9th century, Slavic tribes vied for supremacy but just as they were on the brink of fratricidal war, they invited a Viking prince called Rurik of Rus to rule over them and impose order. "From him did the Russian land receive its name," says the ancient Russian Chronicle.

My most recent visit came via a journey aboard the milk train from Moscow and so, while the town was sleeping, I took a cab to the far side of the Volkhov River. From here, across the water, the full moon floated above the walls of the Novgorod kremlin (the Russian name for a fortified citadel) in one of Europe's most perfect vistas – red medieval battlements planted on green river banks and, rising above them, the high golden domes of a soaring cathedral.

Walk through the gates of the kremlin and you'll find manicured lawns and a statue of Rurik. There's also a fascinating history museum with birch bark documents from the earliest days – merchants' bills, love letters and even schoolboys' crib sheets. The white-walled 11th-century Cathedral of Saint Sophia is Russia's oldest church, with splendid frescoes and a miracle-working icon.

The Golden Gate of Kiev

In 882 Rurik's heirs shifted their headquarters south to Kiev, in what is now Ukraine. Take a bus to the top of the Berestov Hill on the edge of town (you can't miss it – it's crowned by a three-storey-high Soviet statue to the Red Army) and you'll see why they chose it. The mighty Dnieper river bends its way through the gorge beneath you, at the heart of the trade route from the Viking north to the Greek Byzantine Empire in the south.

For the next four centuries, Kiev – not Moscow – was the capital of the Russian lands. When its Grand Prince, Vladimir, adopted Orthodox Christianity in 988, Kiev's Monastery of the Caves became the new state religion's highest holy place. Here, I took a wax taper and wandered through the catacombs, shivering with surprise as I stumbled across the embalmed bodies of its earliest Christian monks.

The Golden Gate of Kiev – commemorated in Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition – was part of the city's mighty walls, designed to keep out the marauding tribes of the wild eastern steppe. But in 1240, a powerful Mongol army smashed down Kiev's defences and murdered its inhabitants. Rus was plunged into the 200-year darkness of the Mongol occupation.

Kulikovo Polye (Field of Snipes)

The Mongols stifled native culture and forced the Russian princes into humiliating shows of submission. Some resisted, but it wasn't until 1380 that 29-year-old Dmitry Ivanovich from the previously minor city of Moscow persuaded his fellow princes to mount a concerted challenge to the occupiers. At Kulikovo Polye, 160 miles south of Moscow, Dmitry assembled his forces on the banks of the River Don and squared up to the Mongol cavalry. You can still visit the battlefield with its 90ft Orthodox cross, church and museum.

Mongol rule would last for another century, but in Russian folk memory Kulikovo Polye is "the place to which Russians came divided and left as a nation". The site has been adopted by Russian nationalists, and every September they re-enact the battle in period costume.

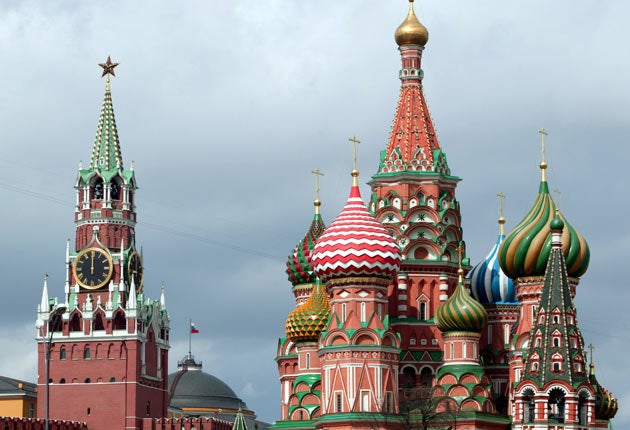

Moscow's kremlin

As Mongol power waned, Moscow's grew. Prince Ivan I, known as Kalita ("Moneybags") because of his knack for accumulating territory and wealth, laid the foundations of the Moscow kremlin in the 1320s. Today its palaces and churches are Moscow's leading tourist attraction. So long as there's no big political set-piece going on, you can tour most of them. And while you're there, pop in to see Lenin in his Mausoleum on Red Square beneath the kremlin walls.

Events from more recent days centre around the Russian White House, the imposing white marble building on the Moscow River, where Boris Yeltsin defied the hardline communist coup in 1991. But none of that would have been possible without Ivan Moneybags. His wheeling and dealing sealed Moscow's pre-eminence, replacing Kiev as the seat of the Grand Prince (the future Tsar) and of the Orthodox Church. In the kremlin's Cathedral of Archangel Michael, you'll find Ivan's tomb at the very beginning of the long rows of Moscow tsars who followed him down the centuries.

Borodino

Russia's borders are long and vulnerable; the fear of invasion has been an enduring national terror myth since the Mongol Yoke. When the French began exporting revolution after 1789, the Russians were ill-prepared.

Napoleon's armies advanced rapidly until they reached the village of Borodino, 75 miles west of Moscow. The ensuing battle, in September 1812, is the centrepiece of Tolstoy's War and Peace, and the subject of Tchaikovsky's rousing 1812 Overture.

These days there are guided tours of the battlefield – it's marked with signposts at key spots – and in a small museum you'll find the bloody uniforms of Russian and French troops. But watch out for the babushkas in charge of the place: I got a very public ticking-off for talking into a tape recorder. The museum explains that Borodino was a defeat for the Russians – their casualties were much higher than Napoleon's – but the French were fatally weakened. They rolled on to Moscow, only to find that the retreating Russians had set the city ablaze. Deprived of food and shelter, frozen by the Russian winter, the half-million French turned homewards. All but 200,000 died in two months of retreat.

Moika Canal, Saint Petersburg

When Peter the Great chose the site of his new capital in 1703, the Russian aristocracy were appalled; it was a swampy, desolate bog on the Gulf of Finland. But Peter's choice was emblematic of boldness and renewal. He was shuffling off the old, backward-looking connotations of Moscow, taking Russia on "a leap from darkness into light". The city that became Peter's "window on the West" is full of wide avenues and splendid vistas, and it has fascinated me ever since I was a student here in the 1970s.

Don't miss the tsars' Winter Palace, home to the incomparable Hermitage Museum; Palace Square where the events of Bloody Sunday unfolded in 1905; and the Battleship Aurora, still anchored at the quay where it fired the starting gun for the October Revolution of 1917.

Spare a moment, also, for the spot by the Moika Canal where Russia's hopes for democracy were blown apart. Here in March 1881, the reforming Tsar Alexander II was torn to pieces by a revolutionary's bomb. He'd freed the serfs and was planning a new liberal constitution, but his reforms died with him. The Cathedral of Spilled Blood, with its marvellous mosaics, now marks the site.

Yekaterinburg

The Siberian city of Yekaterinburg, on the eastern slopes of the Urals, has an attractive centre, set around an artificial lake – and a colourful past. Its place in history was cemented in the early hours of 17 July 1918. The Bolsheviks had imprisoned Tsar Nicholas II and his family in the commandeered house of a Yekaterinburg merchant, but when anti-revolutionary forces threatened to capture the city and free the royals, Lenin sent orders they should all be shot. The spot where the last Tsar of Russia met his fate is occupied by a newly built cathedral, the Shrine of Redemption through Blood, surrounded by billboards showing life-sized images of the dead Romanovs and asking for prayers to "the holy martyrs". The bodies of Nicholas and his family were dumped in a mine shaft and were not discovered until 1991.

Star City

The Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev was plagued by economic problems, but there were areas in which it excelled. I found the story of the Soviet space programme inspiring and horrifying by turns. You can trace its fascinating story at Star City (Zvezdny Gorodok) 50 miles north-east of Moscow.

Star City is still a military zone, but state-approved travel organisations offer guided tours and they are well worth taking. The heroism of the Soviet cosmonauts helped the USSR beat the Americans at every turn, but Khrushchev and Brezhnev became so obsessed with propaganda victories they demanded ever greater risks be taken. Tragedy ensued; cosmonauts died and the space programme went into meltdown. The Americans won the race to the moon and no Soviet would ever follow in their footsteps.

It's a fitting image for the whole communist century, which promised much but ended in failure.

Martin Sixsmith's Russia, a 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East is published by BBC Books at £25. His Radio 4 series marking the 20th anniversary of the dissolution of the USSR continues in July.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments