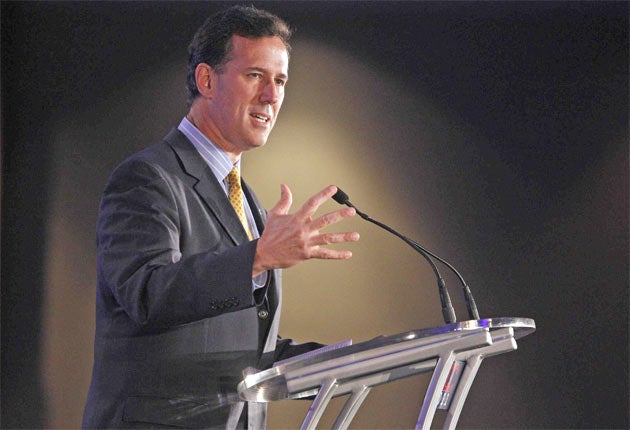

Name game: The slang system has left Senator Santorum feeling very uneasy

We know about sandwich and cardigan, but santorum? The story of how names pass into common use can be eye-opening, by Andy McSmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rick Santorum, who is running for the Republican nomination in next year's presidential contest, does not want his name to become an eponym. This is understandable, when you know what the word "eponym" means – it is a word derived from a person's name – and what the word "santorum" will mean, if a campaign launched eight years ago by a gay newspaper columnist achieves its objective.

In April 2003, Senator Santorum, as he then was, gave an interview in which he likened consensual gay sex within the home to bigamy, polygamy, incest, adultery and bestiality. In revenge, a columnist named Dan Savage ran a competition to create a new definition of the word "santorum".

The winning entry is far too graphic to be reproduced in a family newspaper, but if you search for "santorum" on the internet you will find out what it means before you learn anything else about the former senator from Pennsylvania.

If it sticks, he will not be the first American to have his name used to describe something unpleasant. When the settlers of Virginia were fighting in 1780 to free themselves from English rule, they had to find a way to deter Virginian Tories who stayed loyal to George III, so a local magistrate named Lynch assumed the authority to have suspected traitors whipped or hanged. To "lynch" was originally an honourable act of dispensing popular justice where the official law courts were out of reach – a rough, frontier version of David Cameron's Big Society. It wasn't until the 1830s that anti-slavery campaigners began applying the term to mob violence in the Deep South.

During Elbridge Gerry's final term as Governor of Massachusetts, before he moved on in 1813 to be Vice-president of the USA, he did what the Conservatives are now doing in Britain: he redrew the state's electoral boundaries to increase his party's chances of winning. One of the electoral districts he created had such a peculiar shape that his opponents mockingly claimed that it looked like a salamander. Hence "gerrymander".

There was also a New Hampshire tree surgeon named Earl Silas Tupper, who designed an airtight plastic container.

But enough of Americans. Eponyms season our language. Most refer to long-dead and often obscure Europeans whose names we casually repeat without being aware that they existed. When Bridget Jones noted in her fictional diary that she was going to "spend the evening eating doughnuts in a cardigan with egg on it", she paid an unwitting tribute to one of the worst commanders in British military history. The Earl of Cardigan was a ferocious disciplinarian – or, to use a slightly dated term, a martinet (after Jean Martinet, inspector general of the army of Louis XIV) – and a product of the system enforced by the Duke of Wellington (whose name denoted a boot long enough to cover the knee, but has come to mean a welly of any size) which allowed rich aristocrats to buy military commission. Cardigan bought the Light Brigade, which he led to slaughter at the Battle of Balaclava in 1854.

St Pantaleon, the patron saint of Venice, is usually depicted wearing flared trousers known as pantaleones. Diedrich Knickerbocker was the pseudonym under which Washington Irving wrote, in 1809, a satirical history of New York featuring Dutch settlers who dressed in loose breeches. Amelia Bloomer was an American journalist and feminist who campaigned for women to be allowed to wear something more comfortable than corsets and tight dresses, such as long, baggy pants that narrowed to a cuff at the ankles. Jules Léotard was the French circus performer who inspired the song about "The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze", who wore a tight one-piece body suit to show off his muscles.

Adolphe Sax was a 19th-century Belgian instrument designer, whose saxotromba and saxhorn never caught on, but the saxophone did. Ned Ludd was no inventor. He was a labourer from Anstey, near Leicester, who smashed up his master's machine in a fit of rage, and whose name was invoked by artisans who took direct action when their livelihoods were threatened by the introduction of machinery early in the 19th century.

The Irish contributed a word to the language when they organised a successful campaign to withhold the rent due to the Earl of Erne in protest at the behaviour of his land agent, Captain Charles Boycott.

Franz Mesmer was a German physician who developed a theory about the existence of animal magnetism, which led to the development of hypnosis.

In 1896, a German psychiatrist named Richard von Krafft-Ebing compiled a reference book that described previously little known aspects of human sexuality, including the derivation of exotic pleasure from either dealing out or receiving pain and punishment. To give these conditions names, he turned to literature, naming one after the infamous Marquis de Sade and the other after an Austrian writer, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, whose novel Venus in Furs has a hero who loves to be whipped by his mistress.

Sadism, or worse, lies behind that very unpleasant expression "Sweet Fanny Adams". People use it thinking that it is a euphemism for "f*** all". It is far more unpleasant than that.

Fanny Adams was an eight-year-old girl from Alton, in Hampshire, who was abducted, murdered and dismembered in August 1867 by a paedophile, a local clerk who was caught and hanged on Christmas Eve in front of a crowd of about 5,000. In 1869, there was a change in the diet served to the Royal Navy. The sailors did not like the tinned meat they expected to eat, and claimed that it tasted of "Sweet Fanny Adams" – an example of Victorian sick humour, by comparison with which "santorum" is mild indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments