Hero of Copts; jailed by Swiss secret service; locked in exile

The travails of ex-Egyptian Interior Minister Mohamed el-Ghanem. By Robert Fisk in Geneva

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He is 54 but looks 70 – "like an Indian yogi with a long white beard," as ex-Colonel Mohamed el-Ghanem's Swiss lawyer puts it. "I entered his cell – I had a Swiss official next to me who introduced me. Colonel Ghanem was sitting on his bed. Then he lay on the bed and pulled the blanket up to his chin. He did not say a word – not a single word. For much of the time, he shut his eyes."

Pierre Bayenet specialises in human rights cases but admits that ex-President Mubarak's former Interior Ministry colonel – locked up for six years without trial in a Swiss prison after accusing the Swiss security services of blackmailing him – is one of the strangest cases he has even seen.

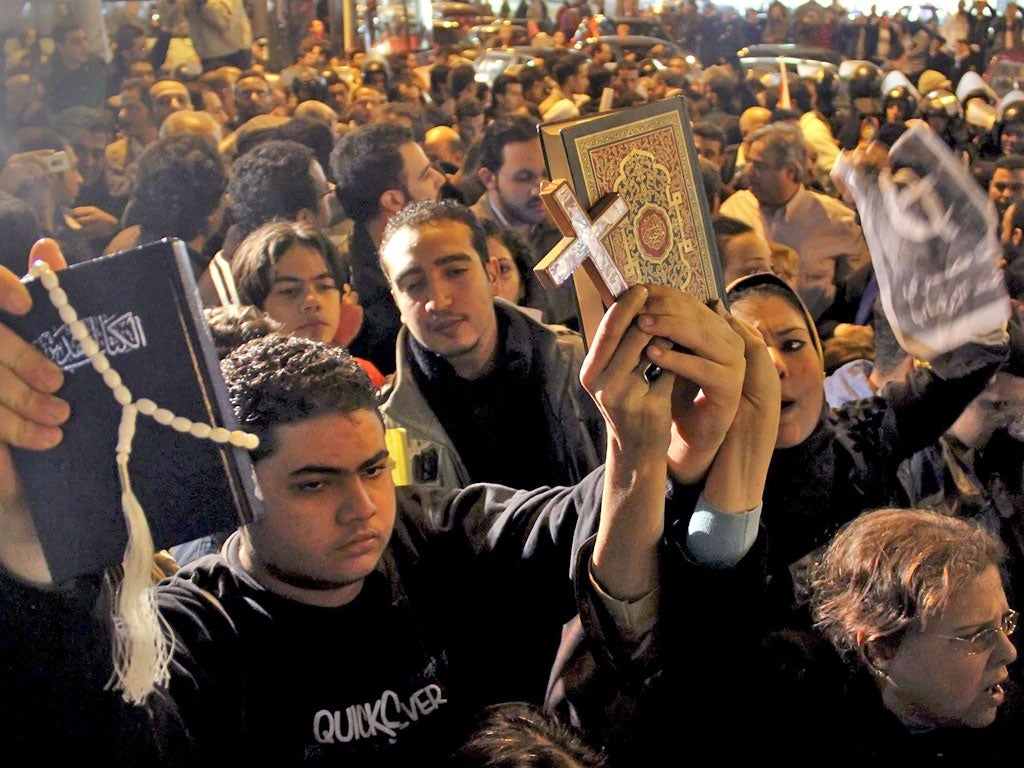

I met Colonel Ghanem in Cairo 12 years ago, a tough, English-speaking military man who opposed Mubarak for his bias against Egypt's Christian Copts, the Egyptian government's corruption, nepotism, torture and human rights abuses. His interview with me provoked a blaze of harassment from the Egyptian security police, until he was given temporary political asylum in Switzerland. In any other world, he would now be a hero of the Egyptian revolution. Instead, he has been fingered by the Swiss security service as a dangerous Islamist subversive.

"He has lots of papers in his cell which appear to have been written by him about his case," Mr Bayenet says. "He lay there with his eyes shut. I told him about his brother Ali's attempt to see him, I said that I was meeting you, Robert. These were the only times he reacted. He opened his eyes and closed them again. He was listening to every word. I told him Ali thought he might be dead. I told him you were following his case. I was in the end rather positive – at least he didn't tell me to go!" Doctors told Mr Ghanem about the revolution. He did not respond.

When I met Colonel Ghanem in the garden coffee shop of the Cairo Marriott Gezira hotel in 2000, he was well-shaven, fit, bespectacled and passionate, a trifle on the plump side but looking no more than his 42 years, raging against Mubarak's refusal to permit Christians in Egypt to build more churches. When he tried to leave his country, members of his own police force turned him back at Cairo airport.

A year later, Colonel Ghanem called me from Geneva to say the Swiss had granted him asylum. He was going back to study at university. But when he called me again in 2003, something had gone wrong. The Swiss secret police were trying to force him to penetrate local al-Qa'ida cells and the Arab community. He had refused to co-operate, he said, and now they were threatening him.

I thought no more of this weird claim until, in 2008, his brother Ali, who lives in Washington, contacted me.

He had been refused permission to see Mohamed el-Ghanem, who since 2007 had been imprisoned without trial – and had been told by the Swiss authorities that Mohamed "did not want to see him".

There is clear evidence that the Swiss secret service has been deeply involved in Mr Ghanem's case and has indeed been seeking to penetrate Muslim groups. In January 2005, Mr Ghanem complained he had been requested to spy on Hani Ramadan, an Egyptian member of the Muslim Brotherhood – now dominating the new Egyptian parliament – who ran an Islamic Centre in Geneva. In July 2004, three years after he arrived in Switzerland, Mr Ghanem filed a complaint about a man who supposedly "bumped into him" in a Geneva street, a black African who allegedly broke his glasses.

Just over a year later, he complained to the police that his phone was tapped and that he was being followed by Egyptian government agents.

Then in February 2005, Mr Ghanem was accused of assaulting a Somali on the campus of Geneva University. According to Mr Ghanem, the man was aggressive and he confronted him with a bread knife. The man supposedly hit Mohamed. After several months of incarceration, Mr Ghanem was released. But then the Swiss security services stepped in. Mr Urs von Daeniken of the Federal Police "service d'analyse et de prévention", the Swiss intelligence service, wrote on 6 October 2005 to the judge who had heard Mr Ghanem's case, quoting from the internet article supposedly written by Mr Ghanem. The letter – a copy of which is in the possession of this newspaper – claimed that Mr Ghanem had also threatened leading Swiss personalities with unspecified "consequences". He was a "violent" man who was threatening the "internal and external security of Switzerland".

Mr Ghanem insists that although he was prepared to defend himself against his alleged assailant in February, 2005, he never attacked the man with his knife. The alleged victim also says that he was never touched by Mr Ghanem, although he says the Egyptian was holding a knife.

But then on 25 October, just 19 days after Mr Von Daeniken's letter, a Geneva police officer wrote to the judge to say that Mr Ghanem had "seriously wounded" an African at Geneva university and had "stabbed him with a kitchen knife in the abdomen".

The police officer – whose name is known to this newspaper – was "obviously lying", according to lawyer Pierre Bayenet, since even the alleged victim said that he had not been touched.

The police officer's letter repeated the internet quotations, adding that these were "alarmist and hateful, repeated over a period of several months... and provoked the kind of reactions you can imagine". The letter made no reference to what these "reactions" were. In any event, Mr Ghanem – who all along had alleged that the Swiss security authorities were trying to coerce him to spy on his fellow Muslims – had now attracted the public interest of the very secret service and police force who were now writing letters to a trial judge.

Colonel Ghanem has undergone psychiatric examination; his lawyer believes he almost died before Christmas. Mr Bayenet also says that – having failed to recruit Mr Ghanem and having then harassed him and made a false claim of assault against him – the Swiss authorities would now like to deport the Egyptian. "But after their claims against him, who would give him asylum now?" Mr Bayenet asks.

"Would he be safe in Egypt? Could they send him back there?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments