I’m a man who has worn make-up since I was seven – not because of vanity, I was hiding something much deeper

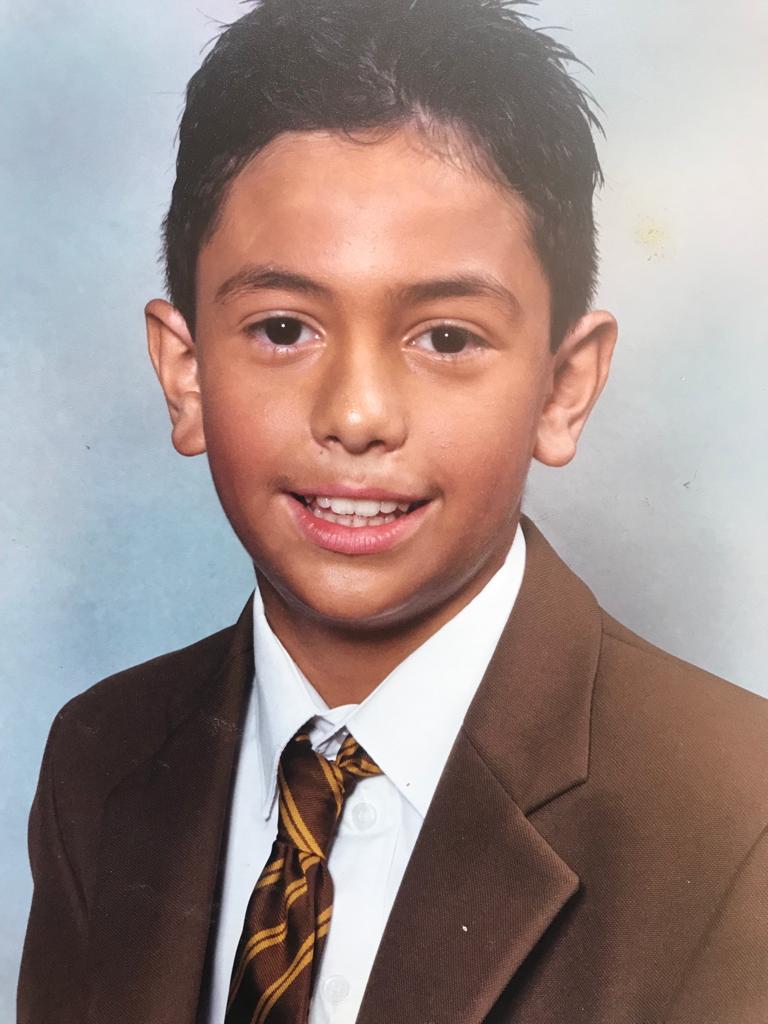

Since he was a teenager, Elj Abid had gone to great lengths to hide his vitiligo, a rare skin condition . Finding the courage to be himself was a day he will never forget

When I was seven years old, a small white patch appeared on the olive skin of my forehead. By the time I was 11, the patches were dotted all over my body, particularly in areas without much flesh, such as my hands, feets, kneecaps and elbows, in an uncannily symmetrical pattern: if you cut me in half, each side would show the same splashes of white.

It was the start of my ongoing journey with vitiligo, an autoimmune disorder that occurs when your melatonin is attacked and destroyed, causing patches of the skin to lose its colour. Nobody knows what causes it, although it is believed there is a genetic component, and it affects one in 100 people in Britain.

For me, its appearance seemed to have been triggered by the emotional trauma of losing my grandad. Since that first white spot 27 years ago, there have been times when the patches have covered huge swathes of my body – my legs turning white from knee to ankle and my face a patchwork of pale and brown. It’s less severe now, although my hands and feet are still predominantly white, but it’s never gone away.

This Morning’s chef Dean Edwards has spoken movingly about his experiences with the disorder, describing how he’d get comments on social media accusing him of vanity, assuming the white patches on his hands were where his fake tan had washed off. The model Winnie Harlow, who also lives with vitiligo, has increased awareness – as well as acceptance – of it, too. But, as I know all too well, the majority of people know very little about it.

Growing up, my Turkish Cypriot family never fully got to grips with what was happening to me. It wasn’t part of my parents’ culture to ask questions of doctors, and my mum, who moved here at 21, wasn’t confident enough in her English to delve deeper. They saw my vitiligo as a purely cosmetic condition, one they needed to help me solve, or at least conceal. When my lovely mum was given steroid creams to apply to my skin and make-up to cover the patches, she assumed following doctors’ orders was for the best.

For 20 years, I wore thick make-up all over my face and the other parts of my body you could see, including my hands. The perceived need to hide my condition dictated everything I could and couldn’t do during my school years: there were no school trips, swimming excursions or sleepovers. I couldn’t even spend time in the sun in case it made the vitiligo worse.

As a teenager, I got into playing football and when I sweated, some of the camouflage would come off, exposing the patches. Kids commented, of course, but I wouldn’t say I was bullied. I was always good at appearing confident externally. The problem was more an internal one. The older I became, the more troubled I felt about hiding who I was – and about the message that, if it was so important to conceal my condition, there must be something truly terrible about it; about me. It made me hate the way I looked.

I realised that my efforts to conceal my condition were actually doing the opposite: drawing attention to me

As well as covering my skin, I was also subjecting it to various treatments in a bid to get rid of the vitiligo, some of which were barbaric. Constantly slathering steroid creams all over myself thinned my skin and caused itching and peeling. I drank a concoction made from tree roots every day for two months after someone told my parents it would help – obviously, it didn’t. I had UV light therapy, after which I had to wear sunglasses for days to try to prevent damage to my eyes.

The worst treatment I received was when I was 14. A doctor based in Turkey gave my parents an ointment to put on my skin which turned out to be a form of acid. Luckily, they didn’t put it on my face, but my leg blistered so badly I had to go to A&E and have a month off school because I couldn’t walk.

Getting together with my now-wife Amy when I was 15 was the start of a gradual awakening for me. The fact that she cared about me increased my confidence exponentially, and her family are much more relaxed than mine – they don’t care what people think of them, and that attitude gradually rubbed off on me.

We went to Jamaica together when I was 21 and still wearing make-up, as well as yet another treatment cream. I spent the entire time feeling hot and uncomfortable, so when we decided to get married there six years later, I realised I didn’t want to repeat that experience. I didn’t want to look back on our wedding photos and see myself sweating under heavy make-up.

The only time anyone ever directly addressed the make-up was during that period. Unlike the chef Dean Edwards, nobody had accused me of vanity for wearing it; it was more of an elephant in the room, never to be mentioned although everyone noticed it. But Amy’s friend said: “Does Elj realise people are staring at him more because of his make-up than because of his vitiligo?” Suddenly, I realised that my efforts to conceal my condition were actually doing the opposite: drawing attention to me.

One day a few weeks before the wedding, I got up for work in the morning as usual, looked in the mirror and thought, I don’t want to do this any more. On the spur of the moment, I found myself throwing my make-up in the bin, walking out of the door and getting on the bus. I texted Amy to tell her I was going make-up-free, and she was so supportive. When the lifts opened at work, the first person I saw was one of my best mates, who took one look at me and threw his arms around me in a huge hug.

That was seven years ago and I haven’t worn make-up since.

That day, and many afterwards, I felt vulnerable, without the armour I’d been so used to hiding behind, but gradually, that faded. I still sporadically use a special cream formulated by a doctor in Germany, which helps keep the vitiligo patches under control, and I have to have my thyroid checked and take folic acid and other supplements. I’m vitamin B deficient, which can make me feel tired. And, at times, I still feel self-conscious, as though people are staring at me. Perhaps they are, but often, I think it’s in my head.

I don’t blame my parents for instilling in me the sense that my vitiligo was something to be kept secret: they were handling it the best way they knew how. But if either of my two children ever show signs of inheriting it, my biggest fear is that they would feel that shame I felt, too. That’s why I’m talking about my experiences, so others suffering like I did might take confidence from me. If I can find peace in my own skin, they can, too.

As told to Polly Dunbar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments