‘It’s like a never-ending punishment’: How the unexpected death of a teenager crushed a family

In February 2012, 15-year-old Jack Thomas settled on to the sofa with his girlfriend and a cup of tea for the second half of a rugby match. Moments later he died. Joel Day tells his story

Sunday 12 February 2012 was crisp and cold, but the low, bright sun hinted that spring would soon be arriving. For Jack Thomas, it felt like everything was coming together. The 15-year-old had just finished his mock exams and was looking forward to the half-term break. Three days earlier, he had been offered a place at Cardiff Sixth Form College, one of Wales’s best schools.

Jack was six foot three and had barely grown into himself. His brown hair was perfectly messy, worn swept across his forehead, and his eyes were a gin-clear blue that caught the gaze of countless girls.

It was around midday when he got up, sauntered across to his mother’s bedroom and collapsed onto her bed to watch a Whitney Houston tribute on TV. The singer had died the night before. “It’s funny that when someone famous dies, everyone gives condolences,” he told his younger brother Owain. “People die every day, and no one cares.”

That morning their mother, June, was taking Owain to rugby training, while Jack planned to go to his girlfriend Emily’s to watch Wales play Scotland in the Six Nations. June asked Jack if she could borrow his coat: “Yes, of course you can,” he replied. “Just as I was about to leave, I said, ‘I love you Jack. I’ll see you later,’” June tells me. “He just looked at me and said, ‘I love you too Mam.’” Those were the last words she ever heard him say.

The Thomas family lives in Oakdale, a village in South Wales wedged between the rolling hills of the Sirhowy Valley. It was a half-hour walk to Emily’s house in the neighbouring town of Newbridge. Jack would normally have cadged a lift off his dad, Grant, but this time, much to Grant’s surprise, he chose to walk. To get there, Jack made his way through tight country lanes and derelict paths, idyllic and still in the winter air.

The match had kicked off shortly before Jack arrived at Emily’s. He soon made himself at home, throwing himself onto the sofa beside her. He ruffled her hair and playfully teased her, and they laughed while watching the game.

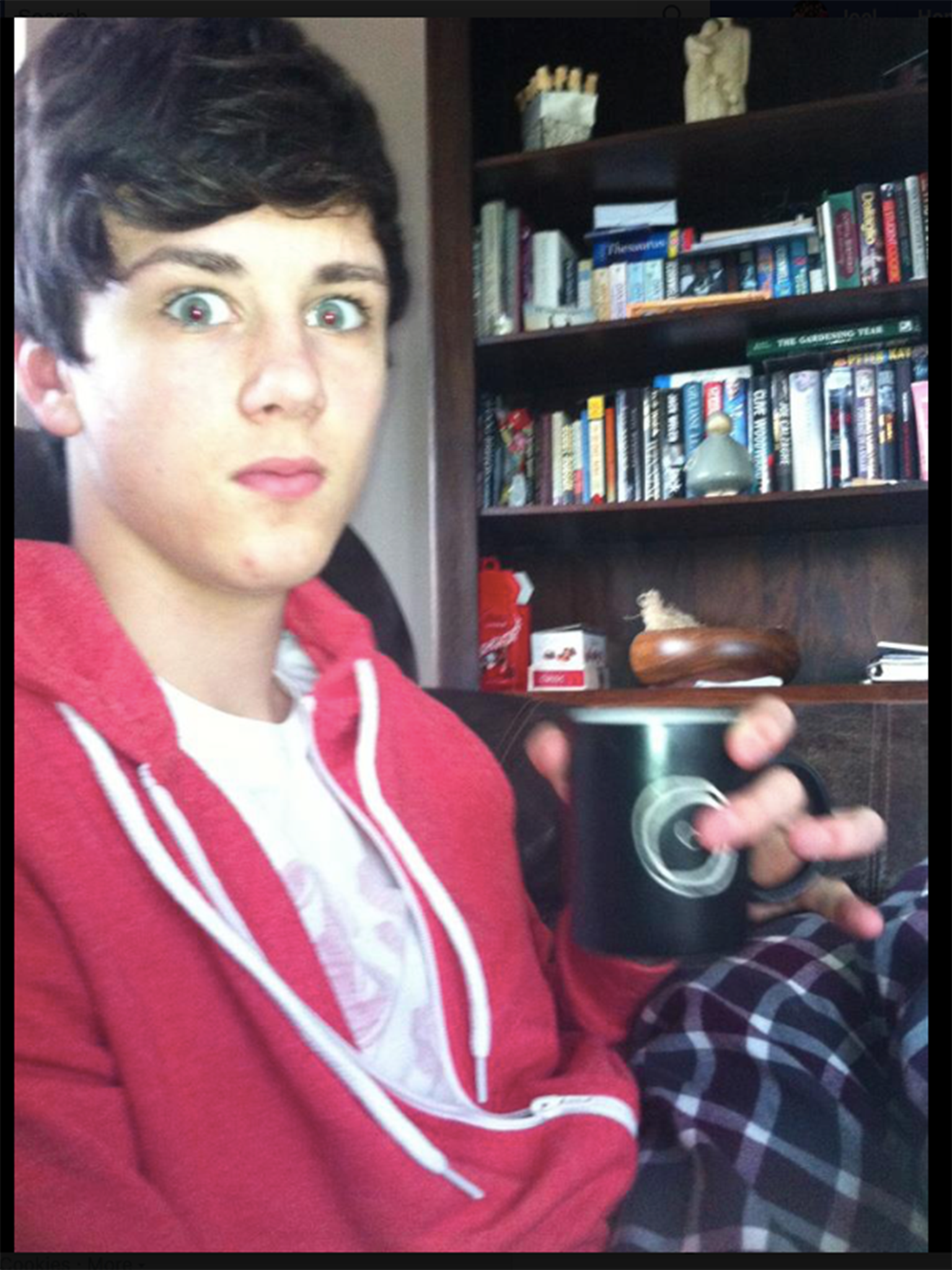

At half-time, Emily’s mum made them all a cup of tea, and Jack went to help. When he returned, Emily took his photograph on her phone. Though far from camera-shy, Jack urged her to “put the camera down”. She did as he asked and rested her legs across his thighs. “It was a perfect day,” Emily says. As Jack put his right arm around Emily’s shoulder, ready for the second half of the match, the cup of tea in his left hand dropped, falling into his lap and staining his sky blue chinos a dirty brown. Jack was dead.

A post-mortem was carried out shortly after Jack’s death. The pathologist found no abnormalities or underlying heart condition, so a specialist cardiac pathologist was called in. Still nothing. The coroner therefore declared the cause of death as “sudden arrhythmic death syndrome” (SADS), meaning simply that Jack’s heart had stopped suddenly for an unknown reason. It was the only way of describing what had happened. But, because SADS is yet to be recognised as a certifiable cause of death in the UK, Jack’s death certificate states: “Death by natural causes, possible arrhythmia.”

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) recently released its most up-to-date figures for deaths in England and Wales. It gives each recognised cause of death a code, including various cardiac conditions. According to the available data, between 2012 – the year of Jack’s death – and 2018, more than half a million people died from cardiac-related conditions. People in Jack’s age bracket, 1 to 34, made up 4,164 of these.

But because SADS isn’t a certifiable cause of death, it doesn’t have a specific ONS code. This means that the ONS has no explicit record of SADS deaths. In 2016, John Pullinger, then the chief executive of the UK Statistics Authority, said in response to a parliamentary question that SADS is instead usually recorded through other codes, such as “R96 Other sudden death, cause unknown”, “I499 Cardiac arrhythmia, unspecified” and “I461 Sudden cardiac death”.

Having to wake up every day not knowing why he died, and knowing that no one can tell us why, that’s the hardest thing. It’s like a never-ending punishment

Between 2012 and 2018, 1,550 deaths were assigned one of these three codes, and so could potentially be attributed to SADS. Of these, 416 were in Jack’s age bracket – about 60 a year. But in his 2016 statement, Pullinger noted that other conditions could potentially be responsible for deaths under these codes. Sudden cardiac death (SCD), for example, covers many different causes of fatal cardiac arrest. It’s impossible to know precisely how big a problem SADS is.

According to Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY), a charity working to improve cardiac health and policy, these figures significantly underestimate the true number of SADS deaths. CRY’s CEO, Dr Steven Cox, says this is because the UK doesn’t have a systematic national registry of deaths from undiagnosed cardiac conditions. He says the figure for SCDs is likely more than 600 annually, or 12 every week – a number much, much higher than what the ONS records. And according to a 2016 paper led by cardiologist Gherardo Finocchiaro, as many as 40 per cent of these SCDs could be caused by SADS.

“There’s no specific code for the ONS to document SADS, so their figures undoubtedly underestimate the actual number of SADS deaths,” says Cox. “This wrongly influences policy, which results in a number of young people living with undiagnosed heart conditions. Their condition will only be highlighted after death, and sometimes not at all.”

This is a problem. Multiple conditions can lead to SADS if left untreated. One, for example, is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an inherited disorder that causes the muscular wall of the heart to thicken and turn stiff. This stiffness can prevent blood being pumped around the body, resulting in an electrical malfunction of the heart that causes instant death. If the true scale of SADS were known, screening for conditions like this could be increased.

But it’s the lack of explanation that comes with SADS that has caused June and Grant the most pain. “Having to wake up every day not knowing why he died, and knowing that no one can tell us why, that’s the hardest thing. It’s like a never-ending punishment,” says June.

In December of 2011, a teacher showed Jack a video of ashes being compressed into diamonds. It captured his attention and left an impression – it was the first thing he told his mum about on bursting through the door after school. “Yeah, all right Jack,” said June. She was accustomed to his outlandish stories. This time, though, it felt different. Jack told his mum: “When I die, I want to be made into a diamond.”

“A diamond was what perfectly described him,” says June, though she admits there were times when he was less than perfect. He was once brought home by the police after being caught throwing golf balls off a bridge with friends in the early hours of the morning. When Grant asked him why he, out of a large group of boys, had owned up, Jack replied: “They only had to look at the CCTV to know straight away it was me – I was the only six-foot-three boy wearing a cow onesie.”

This ability to slip out of trouble and make fun of his wrongs only became stronger as Jack grew older. By the time he was seven “he would twist and turn an argument,” says Grant, “and in the end I was almost always apologetic or laughing.” But this charm didn’t work on everyone; for a spell Jack was bullied, and this pushed him to join a taekwondo club. A year later he became British Taekwondo Champion. He went on to win over 50 gold medals in competitions – a club record that remains unbeaten. It was just one of many examples of Jack’s inability to see barriers. “Life ain’t a dress rehearsal, make it count” was his mantra. At 15, it felt like he had it all.

It was only after months spent sitting on Jack’s bed, listening to Jack’s music and leafing through Jack’s belongings that Owain realised his brother, idol and best friend had gone

A long month passed between Jack’s death and his funeral because of the numerous autopsies. The delay left June and Grant feeling stranded. Their thoughts were trapped in a place where Jack was living, and so their present-day lives had all but stopped. An emptiness crept inside. “Part of our jigsaw was missing,” says June.

Planning the funeral was the hardest part, as June and Grant had no idea what their son wanted. She remembers Jack saying, “When you die, you die, that’s it.” But she wanted some way of him living on outside of her memory. Her biggest fear was that one day, everyone would simply forget him.

If it were not for Owain, both June and Grant admit that they wouldn’t be here. Overnight, Owain went from a 12-year-old boy to a 12-year-old man who made it his duty to comfort those around him. “My world crumbled, but the hand of a child pulled me out of the rubble,” says June.

Owain’s consoling of others was his way of coping. It took him two years to process Jack’s death. At first, it was the missing cup of tea and two biscuits on the kitchen counter after school. Then, it was not having anyone to laugh at Two and a Half Men with. The death broke a routine that Owain had grown to enjoy. But still, it was hardly as if his brother had died; things were just different. It was only after months spent sitting on Jack’s bed, listening to Jack’s music and leafing through Jack’s belongings that Owain realised his brother, idol and best friend had gone.

When Emily visited a Sainsbury’s in a town close to Oakdale several years later, large CRY banners and posters with Jack’s face greeted her at the storefront. “To everyone else, it was just a person, but to me, it was Jack,” she says. Emily is now 23 years old and studies at the Bethel School of Supernatural Ministry, a Christian institution in California. Emily grew up in a Christian household, but her commitment to her faith grew stronger in the years following Jack’s death.

When visiting her home in Wales, she sometimes finds herself scrolling through messages from Jack on her old phone and sifting through a box of his stuff that she can’t bear to throw away: a lip balm he left at her house that day, chewing gum, his T-shirt, the photograph she took minutes before his death. She doesn’t see their relationship as having ended. “It just stopped,” she says. But when she remembers what happened that day, she sees herself as separate from the situation. She thinks about the ordeal that that poor 15-year-old girl went through. She knows it happened to her, but that girl from 2012 has gone.

There are gaps in her memory, but on the Friday before his death, she and Jack spent time talking about what they wanted at their funerals. He shared with her how he wanted to be made into a diamond when he died. Everyone should be dressed in bright colours, he said, because “a death should be a celebration of life”.

The National Screening Committee (NSC) is the body that advises the government on heart-screening policy. There is currently no mandatory heart screening in the UK. This is because the NSC, using ONS figures, concludes that heart screening for people who show no symptoms of illness is needless. It also believes the unreliability of screening – false positives are fairly common in young people who are active and athletic – could render it counterproductive, making otherwise healthy young people unnecessarily anxious and deterring them from exercising.

All too often, the first sign that anything is wrong will be the last

Screening is done using electrocardiograms (ECGs), tests that measure the electrical activity of the heart. If an ECG reveals an irregularity, usually an MRI or ultrasound scan is then carried out to pinpoint any structural damage to the heart. Unexpected results, though, can be symptoms of both life-threatening and entirely benign conditions. If the later test results are normal, then the first test is classed as a false positive.

The time between initial tests and subsequent follow-ups is often long, leaving those being tested on edge. And telling a patient they have a potentially life-threatening heart abnormality, only to find that the initial result was a false positive, could have a tremendously negative effect on someone’s life. But a doctor must disclose what they find. This all adds to the NSC’s case against mandatory screening.

600

Estimated number of sudden cardiac deaths in under-35s each year

But to Cox, this stance makes no sense. Responding to the NSC’s guidance, he writes: “All young people should have the opportunity to be screened, because the majority of young sudden cardiac deaths are not in elite athletes and in 80 per cent of the tragedies there are no signs or symptoms. All too often, the first sign that anything is wrong will be the last.”

It’s true that heart conditions that cause SADS and SCD are often symptomless. And if symptoms do appear, many, such as breathlessness and blackouts, are easily dismissed by GPs. In the Veneto region of Italy, it’s compulsory for young people competing in sport to have their hearts screened; since 1982, SCDs in this group have fallen by 89 per cent. This shows what widespread screening can do and raises serious questions about the NSC’s line of reasoning.

In the meantime, CRY is taking actions into its own hands. Using money raised from donations and fundraisers held by the bereaved, it holds free screening events around the country and has diagnosed previously unknown heart conditions in thousands of young people. If an ECG suggests there’s a problem, the charity conducts all the necessary follow-up scans the same day. Its work has likely prevented a great deal of premature deaths.

Yet, it is not an ideal situation. CRY becomes “something to fill the hole left in a bereaved family’s life,” says Tony Hill, a CRY worker I met at a heart-screening event on the seventh anniversary of Jack’s death. Since 2012, June alone has raised £100,000 and provided over 1,000 people with the opportunity to be screened. The money goes on renting screening machines for the events as well as providing specialist cardiac doctors on-site for immediate procedures and advice. Although this rent-to-screen method works, yearly fundraising and passing the responsibility of saving lives to the bereaved is neither a sustainable or suitable model. “It’s like trying to reinvent the wheel,” Hill says.

When Jack dropped his tea, Emily felt a burning sensation pierce her thigh. She saw Jack’s cup pouring over him and was halfway through asking him what he was doing when she noticed his face was vacant, his mouth ajar.

Emily phoned Jack’s dad and, through sobs, asked him to come to the house. Grant left in a panic, trying not to break the speed limit in his van. When he arrived, the front door was open. Emily and her brother were stood frozen in the hallway. “He’s in there,” said Emily, pointing to the living room. Grant remembers seeing Emily’s dad desperately pumping Jack’s chest. He flopped down by the side of Jack’s head and calmly began to give him mouth-to-mouth. “It was like it was a normal thing to do,” he says.

Grant’s phone kept ringing. It was June, but he couldn’t bring himself to answer. “We were fighting to save our son’s life in that room, how was I supposed to tell her?” Grant would think about what unfolded in Emily’s house for months, looking at the clock every Sunday, recalling what he had been doing at that very second on that very day.

More than 2,000 people attended Jack’s funeral. People he had fought in taekwondo or played football, rugby or cricket with. People from London, Oxford, Cardiff

June was at Blackwood Rugby Club when she got a call from Emily’s mum. She arrived at the house to find Grant, Emily’s dad and the paramedics carrying Jack out into the ambulance. He was draped over a chair, deadweight, his mouth open and a tube down his throat.

At the hospital Jack was pumped full of adrenaline, but he was unresponsive. Grant told the doctors that if Jack was going to respond to anyone, it would be his mother. They agreed to let June into the room, and she stood by Jack’s side. “Prove them wrong Jack, you always prove people wrong,” she whispered into his ear, stroking his hair.

Jack lived and breathed Liverpool Football Club and could reel off every squad from the under-15s to the men’s first team as if they were imprinted inside his eyelids. June, quietly at first, then gradually louder, started to sing the club’s anthem, “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. “I was asking him to wake up, because I didn’t know all the words” she says. An hour passed and, with his heart persistently flat-lining, Jack was pronounced dead. The room was silent. June washed the small pools of dry blood that the tubes and needles had left all over Jack’s body. When Owain arrived, he took his cardigan off and settled it over his brother. “He just looked so cold,” he says.

The hours rolled into each other. Before long it was late evening. Friends had already gathered at the Thomas home, news having spread and sent shock waves through the community. A crowd of Jack’s close friends had gathered in the square in the centre of the village. No one spoke about the death. They talked only about the rugby, what they had been doing that day and what they had planned for half-term. Under the syrupy gold of the streetlights, they stood together and sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone”.

Friday 16 March 2012 was the day that Oakdale came to a standstill. It had been an unseasonably warm month, and the sky was light blue and seemed to go on forever. The roads were closed and the buses on diversion.

The hearse approached the Thomas house. June, Grant, Owain and Emily could see the word “Jack” spelt out in bright flowers on one side of his coffin and “Bro” on the other. Following the hearse in a car behind, they passed parts of Oakdale that had played parts in their lives. First, Jack’s primary school. Then the house he spent his first years in. They stopped. Waiting for them were 24 of Jack’s friends, young men whose lives would never be the same. They walked 12 either side of the hearse as it rolled into the village.

Over 2,000 people attended Jack’s funeral. People he had fought in taekwondo or played football, rugby or cricket with. People from London, Oxford, Cardiff. The church was full, so loudspeakers were installed outside for everyone to hear. The service ended and, as the bearers passed through the church with Jack on their shoulders, his grandfather’s choir grouped outside and began to sing. Roses adorned his coffin, thrown by those who had poured onto the streets; it was almost unrecognisable in a sea of red. Councillor Alan Pritchard, who had lived in Oakdale for 60 years, would later tell Grant that “not a single death has affected the village quite as much”.

That evening they went to Blackwood Rugby Club where, a month before, June had heard the news. There was live music, and the band left the microphone empty while they played Jack’s favourite song. June, Grant and Owain laughed and cried and joked and celebrated and, in the early hours of the morning, the three of them left for home.

An existential angst encompasses June every time she thinks about Jack. It’s an angst rooted in those young sportspeople saved by heart screening in Italy. In her eyes, Jack could and should be among them.

Eight years later, the family are still searching for the cause of their son’s death. A new kind of blood test offered a sliver of hope last year when I visited June and Grant’s home. They talked excitedly about it, their eyes lighting up at the promise of answers. Months later, they still haven’t heard anything. “We’re waiting for science to give us the answer, but not being able to do anything, not having control, it’s just unfair,” says Grant.

June remembers the day of the internment of Jack’s ashes. It was a week after the funeral. An undertaker gave Grant an oak box engraved with Jack’s name, and he placed it into the ground. They scattered soil across the box, and the weight on June pulled her into her mother’s arms. They would visit the plot every day, sitting for hours in silence.

But they kept eight ounces of his ashes in an urn that, by chance, looked just like a sports trophy: two curved handles each the shape of half a heart, with a body that started wide at the bottom, pulled inward and flared out at the top. Those eight ounces were sent to Chicago in March 2012 to be compressed. A year later, a box containing a blue diamond arrived at June and Grant’s home. That blue diamond sits as the centrepiece among several white diamonds in June’s wedding ring. “I’ve got him on my finger all the time now,” she says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments