Why is the NHS lagging so far behind in tech?

In an age where technology seems to advance in leaps and bounds almost daily, Pete Curtis knows firsthand how far behind our health service has fallen – and what it could cost

Towards the end of the 20th century, an entirely new discipline emerged in aviation. An offshoot of a field known as visual science, it led aircraft engineers to change the layout of instruments in the cockpit of a fighter plane. At the breakneck speed of an aerial dogfight, a pilot’s ability to read their control panel might just save their life, so instrument panel layout remains a very important field.

How, for example, should we rank the altimeter in comparison to airspeed? And should either of these instruments be made more obvious than the radar? With the advent of the head-up display, the speciality changed again. Engineers had to decide which information should be projected onto a pilot’s visor and which instruments left on the physical control panel in front of them.

As a doctor within the NHS, I have often wished that this same ethos could be embraced by the health service. Thus far, there has been little or no progress.

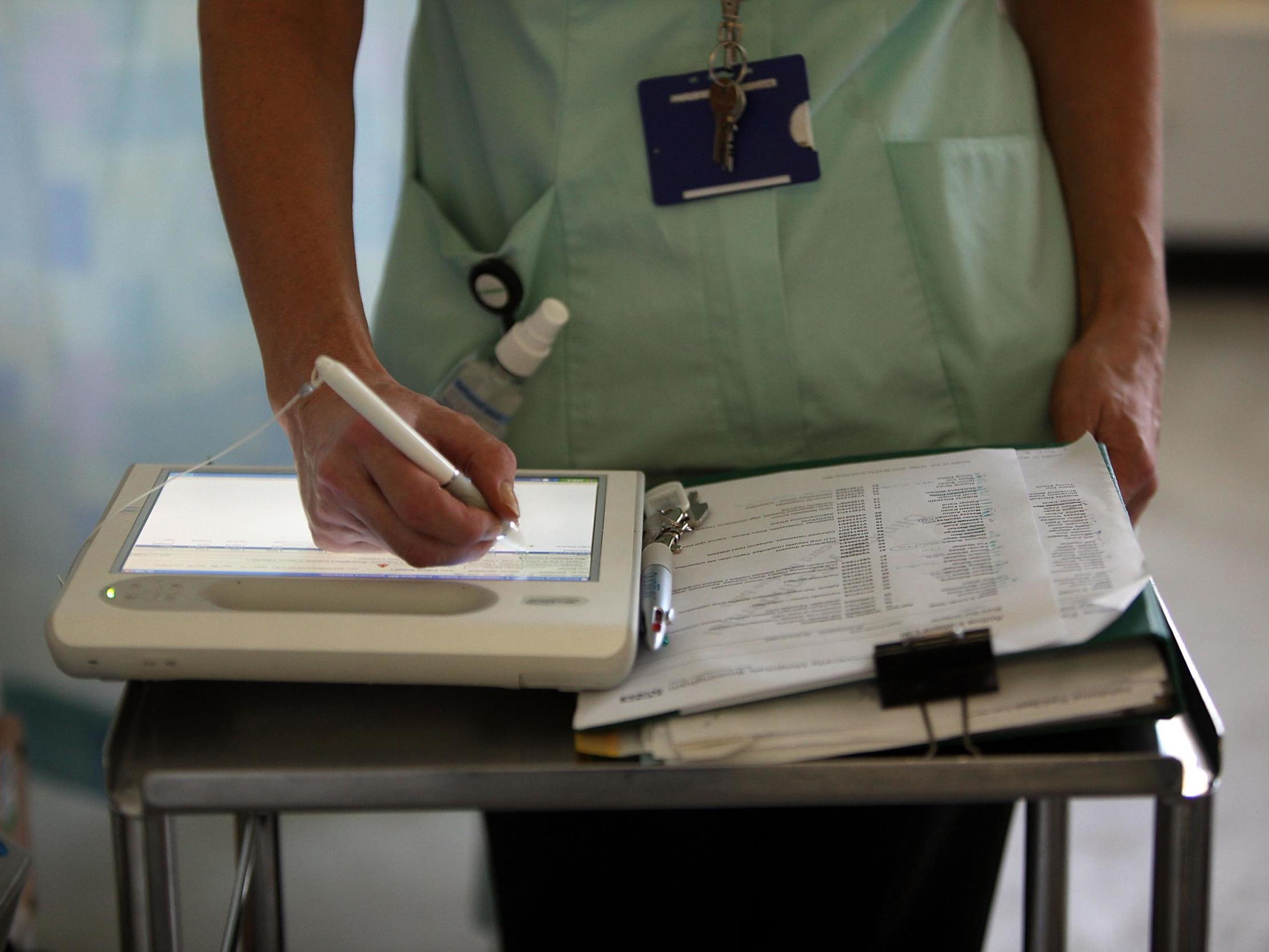

In the closed and largely unpublicised world of hospital record-keeping, little or no emphasis has ever been placed on the end-user. The gap between where we could be and where we actually are is just frightening.

Some years ago, while I was working as a surgeon in a small district general hospital I encountered a badly wounded boy on a ventilator. The thing that sticks in my mind about his initial resuscitation was the sense of haste with which the staff in A&E worked to help him. Following a conversation with the radiologist on call, we managed to obtain an MRI scan of his brain less than an hour after his original injury. I phoned the on-call neurosurgeon at the nearby university hospital and sealed the hard copy scans in a large brown paper envelope. Seconds later, we called a taxi and left the images in a wooden box for the driver to collect.

Needless to say, this kind of process can take an agonising length of time. Two or three hours later, I visited the box where the scans had been left and discovered that they were still there. Startling, but predictable. In many ways, it was just one of the rituals of the job. Eventually, a non-English speaking taxi driver pitched up outside A&E and – after a nightmarish attempt at translation – his car disappeared into the blackness of the night.

Back in the hospital, we sat around for a few more hours. The boy was stable but his condition unchanged, so I decided to go to bed. Later, in the early hours of the morning, the neurosurgeons finally rang to say they had received the scans. When you think about the millions of teenagers using social media to instantly exchange images around the world while this is all happening, you’re left wondering what’s stopping the NHS from going paperless.

That particular unit could not, and still cannot, transmit images electronically. That isn’t to say that no progress has been made. Today, they’d print the images onto a CD-ROM and send it in a different kind of envelope, perhaps smaller and white this time. The punishment for any doctor who attempts to do this via their own email system remains substantial – you can never find a teenager with a phone when you need one.

When you think about the millions of teenagers using social media to instantly exchange images around the world while this is all happening, you’re left wondering what’s stopping the NHS from going paperless

Image transmission isn’t the only area of disappointment. There’s never been a shortage of text documents we don’t know how to cope with either.

When a doctor dictates their notes in the outpatient clinic, they are recorded by an audio typist and stored on a hard drive. As a consequence and in complete contrast to the handwritten scrawl in the ward notes, clinic letters have a clear typeface and stem from the thought processes of a senior clinician. In principle, we could retrieve such letters in the outpatient clinic when we next encounter the same patient. However, the system we’re using cannot be added to the ubiquitous desktops that decorate the outpatient clinic. The material has been dictated, it has been typed and it has been stored, but it cannot be accessed in front of the patients.

Overall, paper notes are finally fading out and in the process, their disappearance has altered my practice. Slowly but surely, I have started to downgrade the attention I give to the patient records.

Notes have become something we retain to reassure other people. It’s impossible to obtain any useful information in the time scale of an outpatient clinic consultation and by implication, the disincentive to read them is quite powerful.

Even prior to the demise of hard copy, I had often been sceptical of the typical wad of A4 sheets they hand you in the outpatient clinic. Like huge Post-its, crucial slips of paper were half-glued to the back pages in predetermined rows. At any one time, at least 10 per cent of them were dangling and by the last gasp another tenth had already vanished. The only really convincing message I can ever retrieve from a patient’s notes is from their size. If you need both hands to pick up the folder, then that patient is a high risk candidate for surgery.

For one patient, we often try to look at ward notes, the previous clinic letter, X-rays and perhaps MRIs as well as pathology results such as blood tests and histology reports. But for each of these there’s a different software and separate password. Delays to the individual consultation or the running of the clinic due to software failure is just routine. The consultant sends messages back to the secretary to print out hard copies, which are then walked down the corridor so that sheet of paper can be delivered to the consultant in the clinic, who can be found making small talk in front of a computer screen.

The idea that we could type in a patient’s name and see all of their results on one screen remains an idle fantasy. If I see 30 patients in a session and I go on to waste two or three minutes on trying to access each patient’s records, I’ve wasted over an hour out of a three-to-four-hour clinic just waiting on data acquisition.

Whenever I hear about an NHS IT contract that has gone wrong for 10 billion quid, I always ask the same question: could I have written something better than that on a VIC-20 when I was 14? If the answer to this question is yes, then I start to get worried

Exactly why this state of affairs continues is difficult to say. From the perspective of the software industry, the hospitals of this world represent a rich and generous market. They have huge budgets, there are lots of them and all of the doctors in the developed world have more or less the same demands. In spite of all this, the NHS continues to live in a perpetual fugue state, unable to determine where it should go or how it should go there. There is simply no medical equivalent to the Microsoft Office system.

Said system can certainly be criticised; that it has achieved a near-monopoly on the global PC market can feel undeserved. It does, however, serve an Esperanto-like function to most of the world’s computer users and the medical world could do a lot worse than seek to emulate its success.

As far as the NHS, both the stationery and the software varies wildly between units. The practical implications of this become more obvious when one considers that the junior medical staff move units every six to 12 months in the first few years of their careers. At any one time, a junior doctor on the wards has less than 12 weeks of familiarity with the request forms and the software systems. In all the years I worked in the NHS, it never ceased to amaze me how dumb this situation was. Almost every unit in the country wastes time and energy designing its own stationery and its own request cards. Later on, they waste more money printing them out in small batches. I don’t think I ever saw two full blood count forms that were the same, although after a few years it became obvious that they were all saying the same thing, albeit in a different dialect.

The system is designed to maximise the risk of clerical error. Nobody ever talks about it and nobody ever reacts to it. I put this to someone quite senior in management, who said that no, it had not designed with the intention of achieving that result, “and I think we can both agree, that’s what really matters”.

In effect, each software house jealously guards its own package and compatibility is rarely, if ever, prioritised. The packages are purchased individually over a period of many years and function at fundamentally different speeds. For example, the pathology system in my current unit is significantly older than the junior doctors who use it. At times, it looks and feels like a non-ambulant version of Space Invaders.

Whenever I hear about an NHS IT contract that has gone wrong for 10 billion quid, I always ask the same question: could I have written something better than that on a VIC-20 when I was 14? If the answer to this question is yes, then I start to get worried.

But if you really are that fed up with what the system offers you, why not act on your own initiative and write your own? I remember seeing a theatre management system in the West Midlands that truly took my breath away. It was the kind of thing I’d been waiting for for years and put an end to the handwritten scrawl of the traditional operating surgeon’s notes. Almost uniquely, it had been conceived and written by a surgeon and it did what it said on the tin, right up until the moment when the hospital management insisted that we had to stop using it.

In the face of the rapidly expanding technology in your pocket, there has been a rebellion of sorts. I’ve worked with doctors who secretly text images to one another, usually using WhatsApp. A number of juniors have tried to contact me with images of a mangled limb on their iPhone

If you’re a doctor and you’re not so hot on computer programming languages, you can always buy a package yourself. An audio typist costs money but in the age we live in, they ought not to. A while ago now, I worked with a colleague who had a dual practice. One was here and the other was in Africa. My colleague realised that he could save $2,000 a month by buying voice recognition software. The package cost him less than $200 and it worked. Back in the UK, he broached the issue of voice recognition software. Did management mind if we bought that? It would take the NHS 18 months to set up a committee to look into it. In part at least, the delay could be explained by the difficulty in obtaining the cash required to pay for such a learned committee. Curious to test the new technology, I offered to buy it with my own money and was warned in writing that such an action would carry the risk of immediate suspension. All the software on the system must be internally approved and I had already been told that this would take 18 months.

In spite of this and in the face of the rapidly expanding technology in your pocket, there has been a rebellion of sorts. I’ve worked with doctors who secretly text images to one another, usually using WhatsApp. A number of juniors have tried to contact me with images of a mangled limb on their iPhone.

“What does it look like?” I ask them, expecting a lengthy reply.

“It looks like this.” They answer, and a few seconds later, a fantastic colour photograph leaps up on my screen.

And you know, the crazy thing is, it usually does look like that. Do images like this help with clinical care? Yes, of course, colour image transmission can help. Do they speed up the management of the patient? Clearly. It might even have saved a man his leg, but if the system had become aware of this process they would have taken legal action against each and every one of the clinicians involved.

The potential to go further is fantastic. There was a time when I might have had to lecture you – the reader – as to how digital systems might change our lives. That time has gone. Most probably you’re already using vastly superior systems on the device in your pocket.

Once upon a time, we used to be able to dial zero and telephone the operator in our hospital. In a bid to cut down on the number of telephonists, the trust installed a speech recognition system. Slowly, very slowly, the telephone handset began to ask you which extension you required. Then it stopped working. After a meaningless conversation, it would simply put you through to the operator.

There is a decent programme on my smartphone but we aren’t allowed to use it. Again, however, the NHS is struggling to keep up with the nation’s children. On our daily ward rounds, we still give verbal instructions to our juniors. True to form, our juniors write something in longhand on a piece of paper that nobody bothers to read. At home and on the move you would virtually never write anything in longhand. Only in a hospital would such a practice continue. Writing the notes is something we do to defend ourselves in court and for the sake of having been perceived to have done it. Why then, do we not dictate verbally into a tablet computer and fill in the blanks? It’s clear, it doesn’t stain or tear and whereas hospital notes only ever seem to put on weight, modern tablets are getting thinner. It’s true that speech recognition systems aren’t always accurate, but it’s true also that we can augment it with a touchpad and that it will never be any worse than a doctor’s handwriting.

The main obstacle here is confidentiality. Data must be accessible but it cannot be hackable and the more you digitalise it, the more likely it is that someone very dodgy will attempt to get their hands on it. What I’ve talked about here, will, however, happen. It is a near inevitability. Whatever legal and economic barriers exist to such a future, they will be overcome. In part, at least, hospital’s reluctance to digitalise data stems from the fear of leaking confidential information, but if the Pentagon is willing to take this kind of risk, surely the hospitals of this world will ultimately follow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks