The French gynaecologist who turned Casablanca into the sex change capital of the world

The work of ‘celebrity’ gender reassignment surgeon Dr Georges Burou, whose clients included the late, great Jan Morris, is still a defining debate of our age, writes Oliver Bennett

Casablanca is an anomaly in Morocco. Much of it is commercial, urban and Europeanised, with art deco parades, shopping centres and parks laid out in the early 20th century. Despite the towering Hassan II Mosque, the crashing Atlantic coast and a certain raffish appeal, it lacks the tourist-trapping atmospherics of Marrakesh and Fez.

But the “white city” set one marker in history – as a key location in the history of gender reassignment surgery, or GRS. From the 1950s to the ’70s, Casablanca became the fabled destination of people wishing to transition from male to female, courtesy of glamorous gynaecologist Dr Georges Burou – including Jan Morris, who died last week and who at 45 years old in 1972 went to see Dr Burou for GRS. Her account, in the 1974 book Conundrum, is a classic in its field, and introduced Britain to the idea of what was then known bluntly as a “sex change”.

In an admittedly small field, Dr Burou was arguably the first celebrity of GRS. “Arguably” because Burou had competition from US army veteran Stanley Biber, who from the late 1960s onwards turned Trinidad, Colorado, into the nominative “sex change capital of the world”, performing four sex reassignment surgery, or SRS (as it was then known), operations a day, while another contender was Elmer Belt, until the late 1960s was said to be the first surgeon to perform SRS in the US.

But Dr Burou had European fame and celebrity clients, and became well known in the UK in the 1960s and ’70s, with Casablanca becoming a byword for transgender individuals wishing to change gender, including Morris, model April Ashley in 1960, and singer and model Amanda Lear, whose surgery was said to have been carried out in 1964 and apocryphally paid for by her patron Salvador Dalì. It is said that Dr Burou’s fee was $1,250, which would be more or less $10,000 today – a bargain.

In recent years, the subject of GRS has become a huge and contentious part of public discourse – indeed, it’s no overstatement to say that it has become one of the primary ethical issues of the day. Because of that, it sometimes feels as if GRS is an issue that has landed in the last 10 years. But it has far deeper roots and in the modern era is thought to be about a century old. The first reports of GRS – although they are contested – are normally said to have originated in Germany in the 1920s, when male-to-female GRS was influenced by sex research pioneer Magnus Hirschfeld at Berlin’s Institute for Sexual Research during the 1920s and early 1930s.

There was also a centre in the UK where it found early fruition – the Charing Cross Hospital on Fulham Palace Road. Here, the most celebrated patient was Mary Edith Louise Weston, England’s best female shot putter between 1924 and 1930 and a leading javelin thrower in 1927. In 1936 Mary became Mark after two operations performed by South African surgeon Lennox Broster at Charing Cross and two months later married Alberta Bray in Plymouth. In a line that would hum with conflict were it on Twitter today, Broster said: “Mr Mark Weston, who was always brought up as a female, is male, and should continue life as such.”

Such liberalism was helped by a groundbreaking article in Physical Culture magazine of January 1937 by one Donald Furthman Wickets called “Can Sex in Humans be Changed”, citing both Weston and the Czechoslovakian athlete Zdenek, who won the 100 metres at the Olympics. “Sports writers called him ‘the fastest woman on legs’,” wrote Wickets, in another line that would occasion a contemporary Twitter-storm.

Controversies aside, their work paved the way for the post-war era; and Dr Burou himself. A maverick gynaecologist, the Frenchman had been bought up in Algeria where he had a medical practice but, with a touch of the renegade, was forced to leave after performing illegal abortions and was struck off by the French Order of Physicians.

Of course you can’t do an operation if it isn’t available. Let’s say it’s like wanting to fly but not being able to grow wings

A keen sailor, Burou settled on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, and landed at Parc Clinic near Avenue Hassan II in central Casablanca, where he then built up a reputation for abortions, IVF and, finally, SRS/GRS. Casablanca became the storied mothership for those who wanted to transition from male to female – then the most viable direction of travel, surgically-speaking.

Burou’s breakthrough in public consciousness occurred in 1956 when a Parisian singer at Le Carrousel club called Jacqueline Charlotte Dufresnoy, or Coccinelle, went to see him for GRS. With the door opened, news spread to the UK and April Ashley became Dr Burou’s ninth patient and the first Briton to have GRS in 1960.

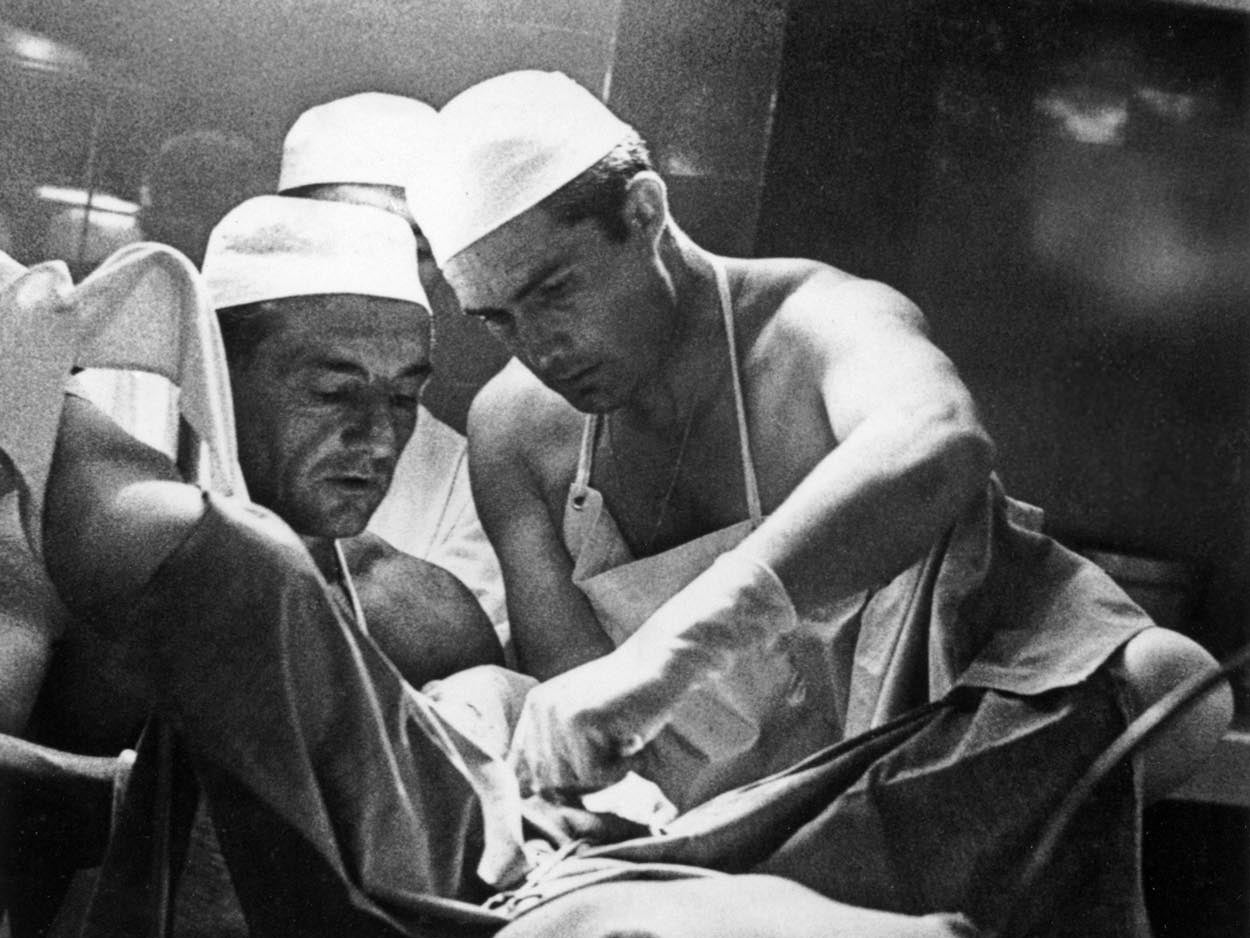

His “one-stage” GRS was known in medical gobstopper language as “anteriorly pedicled penile skin flap inversion vaginoplasty”. This became the “gold standard of skin-lined vaginoplasty” with a so-called “neovagina” created between the rectum and prostate, lined with skin tissue taken from the penis and scrotum, completed with labia and clitoris.

Dr Burou, in a 1974 interview in Paris Match, described his work in the language of the time: “I started this speciality almost by accident, because a pretty woman came to see me,” he said. “In reality, it was a man, I only knew it afterwards, a sound engineer in Casablanca, 23 years old, dressed as a woman … with a lovely chest which he had obtained thanks to hormone bites.” The patient had told Dr Burou that he felt his body was an accident, and although the surgeon had apparently been unaware of the operation’s history, he went on to undertake a three-hour GRS operation, claiming afterwards that “I made her a real woman”.

The Parc Clinic then became the go-to place for male-to-female transition. By the 1970s, Dr Burou had performed between 800 and 3,000 such operations, though the true numbers are difficult to measure in a semi-clandestine milieu. Those seeking GRS with him had to put in the groundwork, find out the location of the clinic and deal with the considerable logistics.

There was also a significant risk. As April Ashley wrote about her decision to see Dr Burou in 1960: “In Paris, I debated with myself the decision to have a sex change. I knew I would be pioneering a dangerous operation. The doctor told me there was a 50-50 chance I would not come through. However, I knew I was a woman and that I could not live in a male body. I had no choice. I flew to Casablanca and the rest, as they say, is history.”

In Paris, I debated with myself the decision to have a sex change. I knew I would be pioneering a dangerous operation … However, I knew I was a woman and that I could not live in a male body. I had no choice

Over the years the cloak-and-dagger mist started to lift and Dr Burou became a medical celebrity, helped by the spirit of sexual freedom and fluidity that infused the late 1960s and ’70s. In February 1973, for example, he presented to the Medical Congress of Transsexuality at Stanford University in the US, followed by the International Congress of Sexology in Paris in 1974. Time magazine included him in a report about “prisoners of sex”. There was even an unsubstantiated rumour that one Michael Jackson had passed his way. The world was coming around to GRS, assisted by avant-garde medics like Harry Benjamin in the US, who changed medical attitudes by creating a distinction between gender identity and homosexuality: then assumed to be the cause of gender dysphoria, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders changed so that homosexuality was not classified as a mental disorder in 1974, the same year as Morris’ Conundrum was published.

Even the puritanical UK saw powerful currents of change. The case of Corbett v Corbett in 1970, the divorce between April Ashley and her husband Arthur Corbett, saw the judge ruling that Ashley was a biological man and the marriage invalid, which caused a stir and fuelled the cause. In Conundrum, Jan Morris revealed that she had been refused GRS in the UK because of the pre-condition that she should divorce her wife, which she didn’t want to do. The academic Carol Riddell, also a British patient of Dr Burou’s in 1972, had faced a punitive waiting period in the UK. Their combined cases set a precedent that helped lead to 2004’s Gender Recognition Act, allowing people to change gender.

Now, Dr Burou’s work has found another historical moment. Dr Vincent Wong, a plastic surgeon working in the sexual dysmorphism field – particularly with feminisation and masculinisation in faces – has worked with several transitioning people including Talulah-Eve, the first transgender contestant on Britain’s Next Top Model, who said: “I knew how I felt in the inside, but I didn’t know how to project that on the outside.”

Dr Wong “dislikes the whole concept that GRS is something new”, and delivers lectures about its history, aiming to show that this transitioning is not some new fad. “The general public might see it as a hot topic but it’s evident that transgender people are not new,” he says. “The mismatch between the outer and inner person is not a trend. It’s been around since the beginning of time. But finally people are a bit more accepting.”

Prior to surgery being available, Wong believes, people would find other outlets, for example, by dressing differently. “What we call drag now has happened for a very long time,” he says. “But it has not been easy and in the past patients were seen as having serious mental health problems.” And while male-to-female reassignment was once more common, as with Dr Burou, Dr Wong says that female-to-male reassignment has now become more dominant and people “are making the decision a lot younger” – although he qualifies this with a certain “worry that the kids are truly questioning their gender or doing it because a friend has”.

Eric Plemons, a medical anthropologist at the University of Arizona and author of The Look of a Woman, has charted the growth of GRS, and notes how the way was paved by “mavericks such as Dr Burou and Biber”.

“Dr Burou was in north Africa, outside of Europe and the US, and therefore he worked in an area that was geographically as well as sociologically marginal,” says Plemons. “There was a kind of glamour there, but remember, it was highly risky. The loss of blood was immense and only in the microsurgery of the 1980s and beyond has it become safer.”

The vaginoplasty of Burou was more more easily undertaken than the phalloplasty of the female-to-male transition. Although this too has a surgical heritage dating back to pre-Second World War, it has lagged behind vaginoplasty – but again, has become easier since the 1980s. Such operations are not about demand but obtainability and viability, says Plemons: “Of course you can’t do an operation if it isn’t available. Let’s say it’s like wanting to fly but not being able to grow wings.”

The acceptance of the trans identity has been more complicated, says Plemons, himself female-to-male transgendered. “An anthropological view would be that the old ways of resource distribution have cleaved down male and female lines for so many years that without them a certain chaos ensues.” Perhaps we are witnessing that chaos at present, and in a similar spirit, Wong emphasises that transitioning isn’t itself clear-cut. “Transitioning isn’t a start and end point,” he says. “It’s a life long journey.”

Dr Burou, long keen on watersports, died in 1987 when his boat capsized in a storm off Pont Blondin, to the north of Casablanca. The maverick surgeon might have been astonished at how his operations, conceived in the absence of other opportunities, had become such a defining debate of our age. At the same time, he would sure have been pleased at how well it worked out for his most celebrated patient, the extraordinary writer Jan Morris.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments