My parents disowned me for being gay, but they have just weeks to live – can I forgive them?

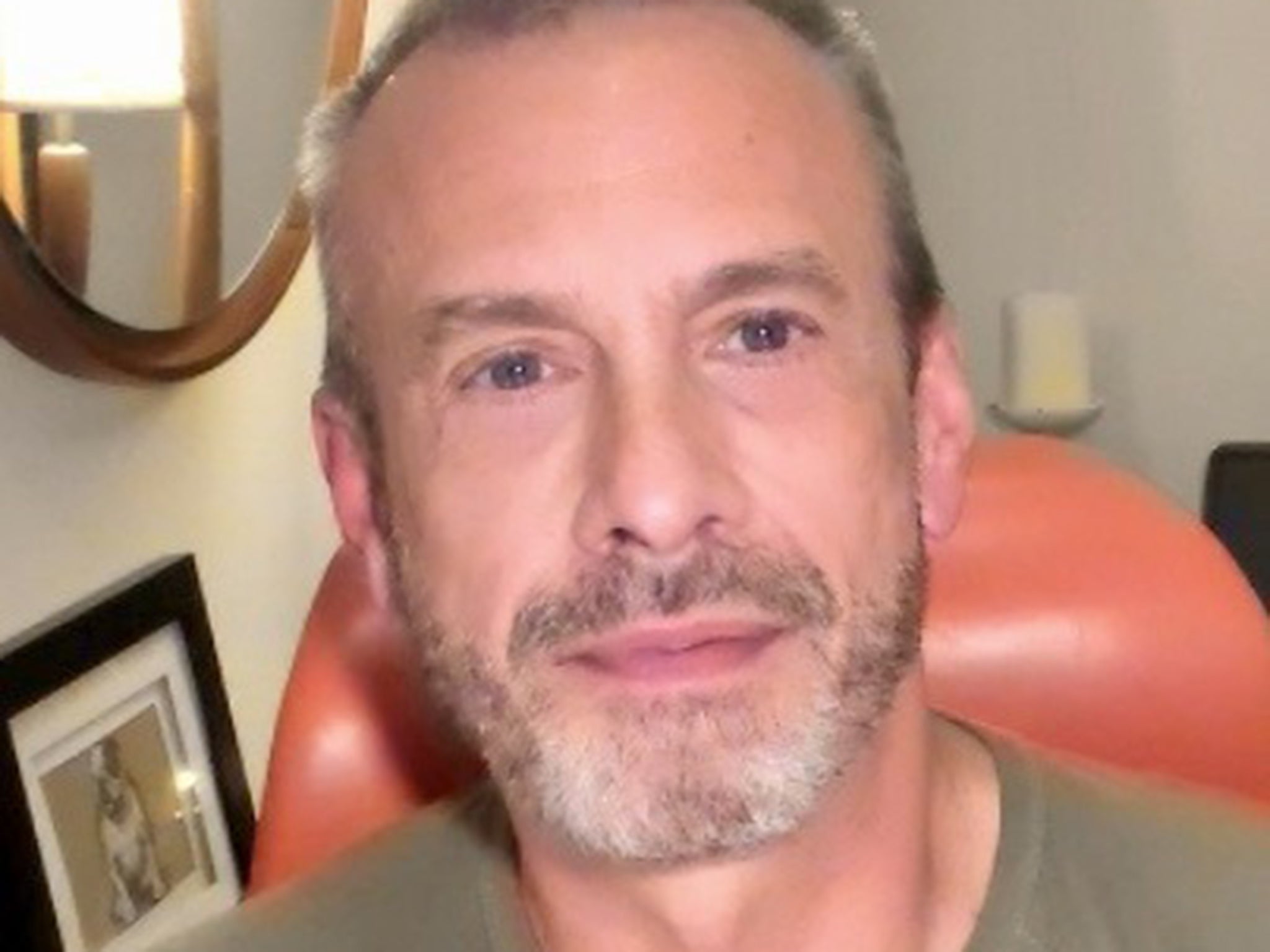

His parents are close to death, and just this week he almost died himself. It has left Alan Downs, celebrated psychologist of the modern gay psyche, in a reflective mood. He speaks exclusively to Gary Nunn

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear to me,” Alan Downs says, “I’m sharing more with you than I ever have anyone else.” Downs is far more accustomed to being in my position: listening intently to clients sat opposite him on the couch. He’s a clinical psychologist. This time, I’m listening intently as he shares something that, for most people, would be extremely painful: both his parents are critically ill. It’s likely they’ll die any day now.

But for Downs, the grief comes with an element of resignation. “It’s a sadness I’ve come to realise I have to accept in life,” he says with the gentlest of sighs. But that acceptance, that resignation, isn’t about them dying. It’s about the fact they haven’t seen or spoken to him in more than 11 years. “I’ve never had accepting parents,” he says. “It’s a loss and a hunger that’ll never be satiated.”

Downs’ parents have never wavered in their opposition to his sexual orientation. “I grew up in a family that’s even more conservative than the Jehovah’s Witnesses,” he says. “If that’s possible.” Once they knew he was gay, his Pentecostal parents were definitive. “My mother said: ‘We will never discuss this again.’ And we never did.” That was 34 years ago.

Today, both his parents are in their nineties and very frail. His dad was recently taken into hospital; he has fallen so often he has internal bleeding and isn’t able to walk. His mum can’t stand for longer than a couple of minutes. “My parents will likely die before reconciling this,” he concedes. “In this life, I didn’t get parents who were loving.”

This is a story about life imitating art: Downs is personally experiencing some of the painfully raw scenarios he discusses in The Velvet Rage, his seminal book about overcoming the pain of growing up gay in a straight man’s world. The book focuses squarely on gay men – which form Downs’ niche client base as a psychologist.

For many gay men who know about it, The Velvet Rage has become something of a handbook to understanding themselves and the world around them in classic psychological terms – from their childhood, through their parents’ eyes, and into their resulting behaviours today. In some gay circles, “velvet rage” has even entered into the colloquial lexicon: “Don’t mind me. I’m just addressing my velvet rage.”

When the people who love us shame us, we don’t stop loving them. We stop loving ourselves. And start looking for ways to fit in and survive

Downs drew upon his clients’ stories when writing his book, and many involved the very thing he now faces: the complex and layered grief that comes from being disowned by one’s parents. “Even before we knew it was sexual, we [gay men] learnt at a young age we were different and that we potentially would be unloved,” he says, summarising the book’s premise. “As a kid, being unloved is akin to death.”

That difference, Downs argues, no matter how minor, and even if it isn’t attributed to sexual orientation, is also perceived by those around the young boy who’ll turn out to be gay – and it causes them to “other” him, to treat him in subtly different ways. Neither side may be consciously aware of it. But it happens.

“When the people who love us shame us, we don’t stop loving them,” he says. “We stop loving ourselves. And start looking for ways to fit in and survive.”

This causes gay men to “alter” themselves. It’s a process Downs calls “splitting” – part of which people may recognise in the metaphor of being in the closet: men concealing their sexual orientation altogether. But splitting also occurs after coming out: the desire to fit in, to appear muscular and attractive, to have the fabulous life many expect gay men to lead.

This impacts both the gay man and his parents: “There’s a process where we contribute to our own invalidation – by this altering of who we are. We don’t give our parents the chance to accept us as gay young boys,” he says. “In time, we don’t even know who we are – we’ve been so busy altering ourselves to be acceptable. So in our young adult years we become adolescents again to learn who we are – and that can happen into our twenties, thirties, forties…” Downs adds that this can lead to problems such as addiction – to sex, drugs or alcohol.

Initially, his parents didn’t accept him being gay, but they continued to have a relationship with him. It was a relationship that became ever more strained. Even as he distanced himself from them, they continued to write, sending him dozens of cards. But inside those cards was always the same message: “We’re praying for you. Jesus loves you. And he wants you back.”

That was, until Oprah came along. Downs was a guest on her show when promoting The Velvet Rage: “I became estranged with my parents when I went on Oprah,” he says. “They said: ‘It’s bad enough you wrote the book. Then you went on TV and told everyone.’”

He’d held off writing The Velvet Rage for many years. “I planned on waiting till they looked like they were going to pass away,” he says. The man who made him change his mind was Ernest Hemingway; specifically, it was one of his celebrated aphorisms: “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

After coming out, I remember feeling this strong need to be authentic and honest from that day forward. As long as I was holding back, I couldn’t write one true sentence. It was either full honesty – or nothing at all

Then another, then another. Before he knew it, The Velvet Rage – which he’d written “already, many times over in my head” – was complete. It was full of nothing but true sentences. And ready for the world.

“After coming out, I remember feeling this strong need to be authentic and honest from that day forward,” he says. “As long as I was holding back, I couldn’t write one true sentence. It was either full honesty – or nothing at all.” This is something he sees a lot as a psychologist specialising in gay men, and it has formed a personal mantra of his own, inspired by Hemingway’s: “Our personal power – mine included – lies in our authenticity,” he says.

With that in mind, he reneged on his promise to himself that he’d wait until his parents were critically ill to publish the book. “I realised: this is my life, this is me. And it turned out as expected.”

He was fully disowned. “The cost of writing my book was losing my parents,” he says of the publication of The Velvet Rage in 2005. His parents fully cut off contact with him, telling him he’d become “the mouthpiece of the devil”. And that they’d continue to pray for him.

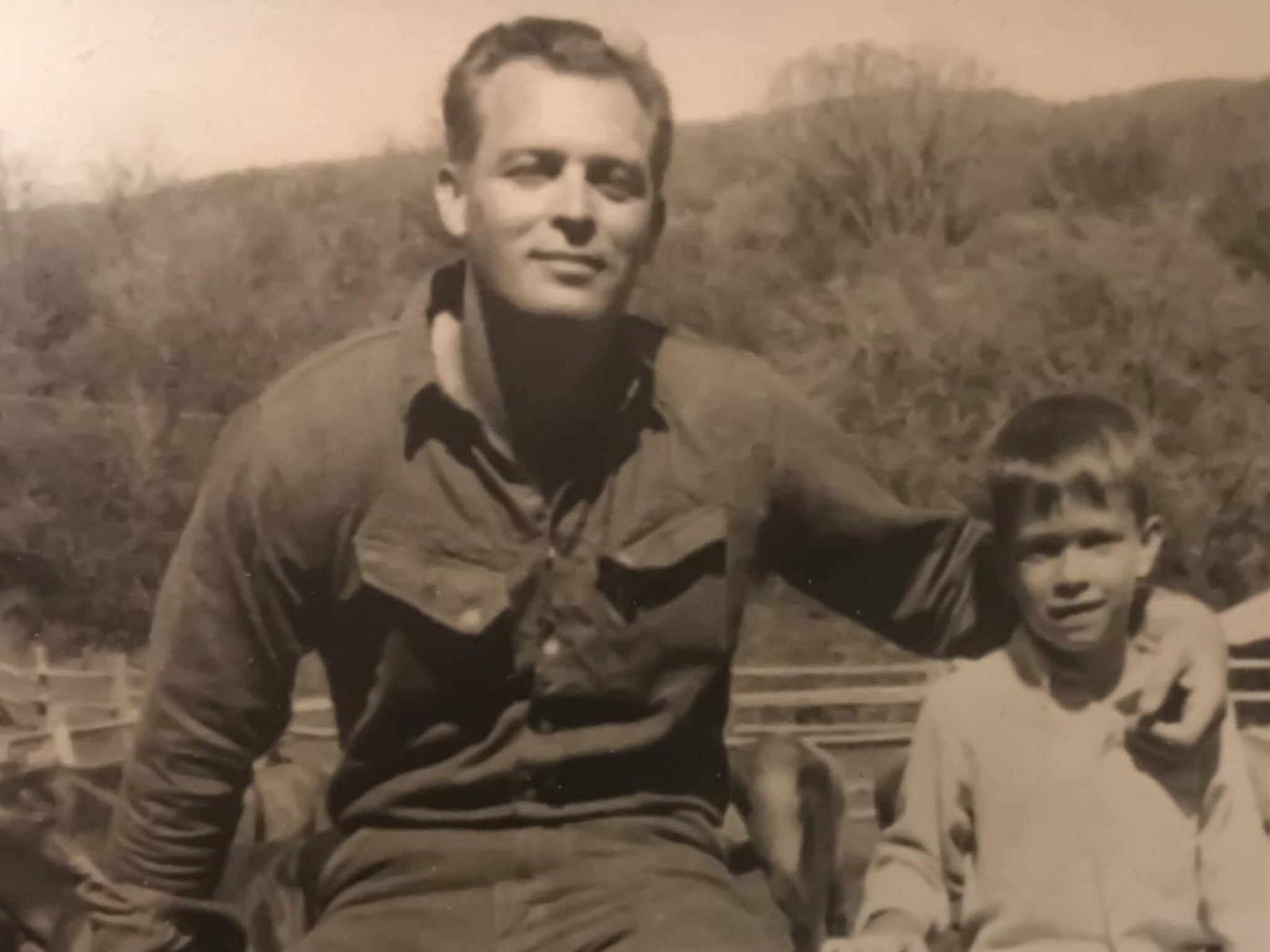

Things had been so different growing up. He’d been very close to his dad, who’d bought him a horse when he was six. But, he says, the first indication he revealed to his parents that he was different was when he named the horse: Nelly. They’d go to rodeos together, but all Downs really wanted to do was braid Nelly’s mane and tail: “I refused to allow her wavy mane to be cut. I played piano. I was involved in almost every activity that macho boys weren’t involved in, I hated sports – clearly I was different. I now know they knew I was different,” he says.

When Downs reached puberty, his dad began distancing himself from his son. Today, he questions whether his dad might have had gay tendencies himself: “He regularly worked out at the gym yet said he’d never met a gay man in his life. I struggle to believe that,” Downs says. “It’s almost as though he was hiding something. But who can say? He wouldn’t talk to me.”

Family is about love. It’s not about blood. My family is and always will be those closest to me that love me

Still, the filial expectations loomed heavily. From the age of 20 until he was 24, Downs was married to a woman. It was when his mum asked why they were divorcing that he came out of the closet with a blunt, rhetorical question: “Isn’t it obvious?”

Whenever he discusses his parents, I notice he always uses the formal “my mother/my father”. Not once does he call them mum or dad. “Family,” he says, “is about love. It’s not about blood. My family is and always will be those closest to me that love me.”

At this point we discuss the TV show Pose, which depicts New York’s Vogue ballroom scene in the 1980s and 90s. Although it focuses on the black and Hispanic LGBT+ experience, Downs relates to the fact that these people chose their own families, having been ostracised by their own communities. “Houses” were led by “mothers” – mostly trans women – whose responsibility it was to champion their “children” – adolescent and young adult LGBT+ people who’d been kicked out of their family homes.

As the show aired, its creator, the prolific Ryan Murphy, was profiled in The New Yorker as “the most powerful man in TV”. In the piece, Murphy cites his biggest influence as Downs’ seminal work. Today, the two have connected as friends – after some mutual fan-girling.

“His biggest strength,” New Yorker journalist Emily Nussbaum writes of Murphy, “is his strangeness, his allergy to the dully inspiring and his native attraction to the angriest characters – a quality he traces to ‘the Velvet Rage’.”

Like the characters on Pose, Downs had a surrogate mum – or as he calls her, “my adopted mum, Catherine” (she is not, I note, an adopted “mother”). He remembers the first time he saw her, in Key West, where he used to live. It was at a dinner party, and the first thing he remembers noticing was her “heavy Southern accent”, which reminded him of home. “She was larger than life, but had this endearing vulnerable side, which drew me to her,” Downs says. She became somewhat of a Key West icon: “She wore Chanel pantsuits and smoked and loved life like I’d never known.”

Whenever a gay man in Key West “overdid it”, Catherine was the first person to “throw them in the back of her car and drive them to rehab and help them recover,” Downs says. The love in his voice is clear. He has become animated and his pace has quickened. Catherine herself had an interesting life – her husband had been Bill Clinton’s personal physician. Downs’ pace slows again as he discusses her death. “I’m looking at her framed picture as I speak to you now,” he says. “When she passed away, I entered into a period of very deep grief. I’m still grieving to this day.” Ultimately, though, the feeling that wins out – in true psychologist form – is gratitude: “I’m at peace now. She made all the difference. I got the gift of being loved by a parent I might not otherwise have had.”

The book made me understand what gay culture seemed to have denied before: that there was a disproportionate problem with our mental health, addiction, depression and so on

Losing his biological parents may have been the cost of The Velvet Rage. But what Downs has gained from the book is also worth reflecting upon.

First, there’s the recognition that he’s helping new generations of gay men better understand themselves and their behaviours as they grow up and live in a straight world. A revised 2012 edition of The Velvet Rage reignited interest in the book, which remains high to this day; last year RuPaul tweeted it to her 1.4 million followers as a “must-read”.

One person the book influenced was Matthew Todd, former editor of Attitude magazine. “I was recommended The Velvet Rage by my therapist, David Smallwood, in 2009,” Todd says. “Both David and the book made me understand what gay culture seemed to have denied before: that there was a disproportionate problem with our mental health, addiction, depression and so on. We’d shied away from facing it because it seemed to suggest being gay was the cause, when The Velvet Rage explained that it was because of how society had boxed us in growing up.”

The book has moved on thinking about the modern gay male psyche. “It seems obvious now,” Todd says. “But it wasn’t then.”

Todd has gone on to become an author himself, with a tract on how to be gay and happy, Straight Jacket, that explores overcoming society’s legacy of gay shame. “I really hope I have added to the conversation with Straight Jacket,” he says. “I think we’re still in the early days of our recovery and understanding of the issues as a community – but we all owe a great deal to Alan Downs.”

Beyond the fanfare and influencing, Downs gained personally from the book too: this was his chance to finally live that authentic life. The Velvet Rage was his seventh book. “At that point I’d had a book in the New York Times bestseller list. I’d been on every talk show. I’d had a double-page spread in Fortune magazine. Never had said I was gay,” he says. There’s a pause as the magnitude of that statement beds down. Years of living a partial truth. Those chasms expanding, contracting. Then finally, release. Full authenticity.

The week we chat has turned out – somewhat unexpectedly – to be a landmark week in Downs’ life. It was his 58th birthday. And he came very close to dying.

A bee stung him; he’s allergic to them and went into anaphylactic shock. He was in hospital for two days while medical professionals irrigated the site of the sting: his face. “I looked like the Elephant Man,” he says of his swollen head. So much so that when he was in the pharmacy to get his prescription, the woman in front of him jumped back, telling him to go before her. It could have been serious; Downs’ uncle died from a bee sting.

This wasn’t his first near-death experience. In 2012, Downs disclosed that he was HIV positive, a decision he says was “almost harder” than coming out, because it was almost as if the warnings of his parents had been vindicated.

By this point, he’d been living with HIV for many years; his was one of the first positive test results in the US. “It was 10 years before any meds did anything,” Downs says. “So I took an irresponsible decision – and I wouldn’t recommend it – I decided I wouldn’t go to a doctor. Not at all. Until I was dying.” This decision – leaving him on what he was convinced was “borrowed time” – was taken because he “didn’t want to spend the time I had left in waiting rooms with dying men”.

At the time, he was living in San Francisco. Death was everywhere. It was devastating: “I’d fought so much to be a gay man. Now if I have sex with another gay man, I could possibly kill him.”

Downs remembers sitting at the bedside of countless men who died. He once picked up the Bay Area Reporter when there were 23 pages of obituaries, all of young gay men. “Twenty. Three,” he repeats slowly. “In one edition. And this was a weekly newspaper.”

Scenes of “beautiful young men who were blinded, walking with canes on the street” after contracting the disease spurred him and his then partner to do what they wanted more urgently. So they both left their jobs. Downs to write; his partner to paint. Then they got the news they’d been dreading: Kevin, his long-term boyfriend, also HIV positive, was unlikely to live to the next day. “The doctor said – and this is something I’ll never, ever forget – there’s this new medication that has just come out. It’s our only hope, and we have no idea if it’ll work.” It did. “It was like Lazarus rising from the dead,” Downs says. And it persuaded him to go on that same medication. This was in 1995.

Today he lives with survivor guilt. “I’d been pretty irresponsible. I danced at circuit parties. There wasn’t a drug I hadn’t taken,” he says. But this second chance at life had a poignant impact on him; it’s when he heard his calling to help others through the therapy he does today. He’s so dedicated to it, he doesn’t travel as extensively as he’d like, say to places like London and Australia; he worries about cancelling appointments with his face-to-face clients who rely on him to get through each week.

Nearly dying before his frail parents this week has forced him to address some difficult questions. “I’m 58; I thought I’d die at 40,” he says. “That was my life expectancy with HIV. Now I have a future I never expected to have. Who’s going be there to walk with me through those years?” His four siblings have a dozen children, but “I’m not permitted to be around them,” Downs says. “I suppose out of the fear I’d molest them or they’d turn out to be gay.” Some do see him now, but as a result of the way they were brought up to be suspicious of him, they’re not close. “Certainly not close enough for them to be the people who’d care for me in my old age,” he says.

One sister doesn’t speak to him; one brother hasn’t reached out in 20 years. “My first books were dedicated to his children,” Downs says. “I never heard anything back from them.”

Fitting in allowed us to survive. We have to be thankful for it – and let go of it. The thing that helped us in adolescence hurts us as adults

But his youngest sister has surprised him. After surviving the Oklahoma City bombing, and despite remaining part of the Pentecostal church, she changed profoundly and began letting Downs in. It culminated in a very special and surprising moment: “She’s the CEO of a credit union with many employees,” he says. “One Christmas, I discovered she’d gift-wrapped a present for each of her gay staff members. It was a copy of The Velvet Rage.” Finally, a blood relative was proud of him and what he’d achieved. “It may have created personal conflicts for her in her life,” he says, “but she has never let me see that.” It’s her he’ll inevitably lean on when the worst happens with his parents, he says.

Now, he’s writing a new book. This time, it’ll be on the main challenge facing LGBT+ people in the next, post-equality, post-HIV decade: intimacy. “It’s the number one issue we’ll struggle with,” he says. With the technology of dating apps and the phenomenon of chemsex (using illicit drugs to enhance sexual pleasure and lose inhibitions), he believes shame is still a juggernaut in the LGBT+ community. “When I hold the belief I’m unlovable, when I’m intimate with another man, eventually he discovers my weakness,” Downs says. “Suddenly he becomes the enemy. He’s seen me at my most vulnerable, the part of me I hide from the world.”

As gay men stop splitting, the final phase they can move into – and this can take decades because it involves addressing and battling their feelings of shame – is “stopping pursuing validation and starting to instead pursue joy,” Downs says. But some gay men get trapped in a Peter Pan cycle, never wanting to fully leave that second phase of discovering who they really are, after concealing it for so long and during such a formative life period. When they do evolve from this stage, he says, the magic can happen: “Fitting in allowed us to survive. We have to be thankful for it – and let go of it. The thing that helped us in adolescence hurts us as adults,” he says. Without shame and with complete authenticity, joy can finally be pursued.

Philosophically, it’s the same authenticity that Downs’ dying parents have chosen: “They’re living their authentic truth as I’m living mine,” he reasons. “This is who they are, and for me to demand they be different only keeps them in distress.”

Ultimately, then, his parents do not accept him and never will. But he has done something remarkable. He has accepted them. “The thing we all pray for so desperately is to be seen,” Downs says. “And that’s the antidote to shame. Shame pushes us to hide.” It’s an aphorism that’s informing the way an entire generation of gay men now live their lives. Openly. Proudly. Freely. Even, sometimes, nonchalantly.

“If I can give that gift – to my clients or to readers of my book – to make them feel seen, it heals my childhood and it heals me,” he says. “I honestly never truly believed I’d make it this far.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments