The Light in the Darkness: Can you make a video game about the Holocaust?

When ‘The Light in the Darkness’ is launched later this year, Luc Bernard hopes it will engage hearts and minds in ways that traditional approaches to Holocaust education do not, he spoke to Stephen Applebaum

Nearly ready to cry,” tweeted Luc Bernard, on 21 January, “finally people are seeing the importance of it after a decade of being punched down.”

The “it” in question is The Light in the Darkness, a video game set in France during the Second World War, and Bernard has been fighting to convince people for years that it could make a legitimate and effective contribution to Holocaust education and Holocaust memory.

Bernard was born in France, and then lived in the UK until re-crossing the Channel aged 10. He now resides in Los Angeles and has, so far, poured $200,000 of his own money into the controversial project and weathered many attacks, both professional and personal, in his quest to bring it to fruition.

We had been in touch for several weeks when he looked through his inbox and discovered, out of the blue, an email from the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle, Washington, asking if they could include his game in their long-running Indie Game Revolution exhibition. For Bernard, it was the kind of recognition that he’d been desperate to receive.

In truth, the combination of the Holocaust and a video game, no matter how well intentioned, was never going to be an easy sell. Whether it be the depiction of the genocide on screen, in a film such as Schindler’s List, or in a graphic novel like Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking family memoir Maus (recently the subject of a baffling ban by a Tennessee school board), a debate has always raged around what is, and what is not, an appropriate way to navigate the systematic slaughter of six million Jews and other victims of Nazi persecution.

In the case of video games – which have generally avoided the Holocaust – the debate surrounds what is often a misconception about the medium, says Bernard. “Older people still don’t necessarily understand video games. They think of Super Mario when really they’re now basically interactive films.”

Though Bernard sometimes still has to work hard to overcome people’s objections and assumptions, there can be no doubt that new ways of introducing young people to the Holocaust need to be found, particularly as the survivors, around whom most education currently revolves, will all be gone soon. Why not utilise the number one form of popular entertainment? “I think Holocaust education used to work well,” says Bernard, “but now everything’s changing. The younger people are different. The way we access information is different.”

In a 2020 study of Holocaust awareness among American millennials and Gen Z adults aged between 18 and 39, commissioned by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), a staggering 23 per cent of respondents said they believed the Holocaust was a myth, or had been exaggerated, or they weren’t sure. In a survey led by the same group in the UK last year, the figure was 9 per cent, while 52 per cent of all respondents did not know that six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, with 22 per cent thinking that the figure was a million or fewer. Could video games become part of the solution by offering another way of opening the door to the subject, rather than simply being dismissed?

“As a medium they can engage with difficult histories in a sensitive, pedagogically sound manner,” says Daniel Panneton, the manager of the Online Hate Research & Education Project at the Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre in Toronto, which hosted an online discussion entitled The Holocaust & Digital Memory, on Holocaust Memorial Day, which involved Bernard and David Klevan of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. However, he cautions, “even well-meaning projects can potentially spread misinformation and distortion or reduce the gravity of the history to an easily consumed and forgotten digital experience.”

Bernard is attuned to the potential pitfalls and regards distortion as a greater, more insidious danger than Holocaust denial. “When someone denies the Holocaust you think, ‘oh, you're crazy. F*** off.’ But distortion is worse because you’re minimising it or comparing it to some things which it shouldn’t be compared to. Like: ‘hey, maybe we can make some comparisons with other genocides.’ But the Holocaust was an industrialised genocide. From the way the Nazis did the census using IBM punch cards, everything was industrialised, and done from within society. And to really understand it, you have to understand antisemitism.”

I want to break down the doors so that everyone has access and can learn about this subject and actually be passionate about it

Bernard is a secular Jew. His Jewish roots would likely have remained hidden from him, however, had his maternal grandmother – who raised him in England until he was 10 – not been tracked down by the son she was forced to give up after being divorced from her German first husband.

He knew that his grandmother and her former spouse, known as “Old Man Wolf”, had cared for children who arrived on the Kindertransport, an organised effort to rescue children from Nazi-controlled territory, but this was something new. It emerged that they had met because they were both Jewish communists, and that after their marriage had fallen apart she had gone about erasing anything Jewish about herself, says Bernard. “She basically started changing everything, like her names, and going from man to man, several different marriages. It’s a bit bonkers, but I don’t hold any prejudice towards anything she did.”

Although she never fully grasped what video games were, he says, The Light in the Darkness was, “quite motivated by her, because she knew I always had this idea and she was very encouraging of it, while everyone else thought I’d lost my mind. She thought these stories needed to continue to be told, and she hated Germans. She knew how to speak German but refused. And she refused to step foot in Germany. So one of the last things she did before she died was tell me I had to do it.”

While most of the family were indifferent to the revelation about their Jewish heritage, it fascinated Bernard. When he was 18, he started looking into the Holocaust, and became “kind of obsessed with it.”

At school, the topic had been covered with a single viewing of Schindler's List. “We were all traumatised, and it was great that we were,” he remembers, “but that was it.” This is why he now believes the way the Holocaust is taught is broken. “It’s not broken for people inside cities, where it’s like: ‘do you want to go to a museum? We’ll bring you to Auschwitz.’ But if you’re in a poor school in the countryside, like I was, it’s like: ‘here’s a film. Okay, let’s move on.’ I want to break down the doors so that everyone has access and can learn about this subject and actually be passionate about it.”

Around the same time that he started his research, Bernard got to know some neo-Nazis. He planned to report their activities to the police, but it was in a small community in France and some of his friends knew about his grandmother, and the trips he took to look at the nearby synagogue. He was exposed. People talked, and word got around. Rolling Stone reported that he was beaten and left for dead. “They kind of exaggerated,” he says. “When I read that I thought, ‘that’s a bit much.’ I just got punched up, and that was it.”

Still, it gave him a small, first-hand taste of where antisemitism can lead. Did it make him feel more marginalised? No more than usual, it seems. “When I was in England, the kids used to bully me because I was French. And when I was in France, the kids used to bully me because I was English. In high school, I would mostly hang out with the Arabs because I would just start fighting with everyone non-stop. It was kind of being among the outcasts of French society, pretty much. So, I never felt like I was part of a majority anywhere.”

Despite knowing what it felt like to be on the outside, Bernard struggled with the negative reactions to his first attempt to bring the Holocaust into a game, then called Imagination is the Only Escape, and thereby prove, among other things, that the industry can deal intelligently and responsibly with weighty subjects. While there were people who greeted the concept with enthusiasm, he says there were also organisations that tried to “shame” him.

“I wish, 10 years ago, they would have come to me and been like, ‘maybe this is the way to do it,’ and advised me rather than shamed me. And I’m [still] not happy about that.”

His problems were compounded when the New York Times ran an article headlined “No Game About Nazis for Nintendo”, in which they allegedly misrepresented the game’s content by framing it as a Nazi video game rather than one about the Holocaust in France which was then followed up in the UK by the Jewish Chronicle, who ran a report containing alarmed comments by a survivor. “I then had to call up that survivor,” says Bernard, “and say, ‘no, it’s not going to be Super Mario in a camp, it is a story.’ They were like, ‘I get it,’ hung up the phone, and everything was fine. A week later, the press goes back to him, and I’m like, ‘Oh God!’ I expected better from the media because, in a lot of cases, people didn’t talk to me and just made a lot of controversy.”

The shaming eventually got so bad that Bernard, who says he became known as the “Holocaust Guy” inside the video game industry, reluctantly shelved the project. He suggests that seeing what happened to him may have put other game designers off touching the subject. “Because if this is what could happen to a small indie director, imagine if it was a big director,” he says. “People would be out for blood.”

Even the wildly popular Call of Duty franchise is “too scared to address the Holocaust in its Second World War games,” he says, “and I think that’s a problem. They should do the liberation of a camp in a game because many people now get a bit of their Second World War history from Call of Duty. But it just completely pretends [the Holocaust] is not there and I think it’s kind of erasing it out of new generations’ heads.”

Bernard’s own contribution looked doomed to never see the light of day. Then, in 2020, he received an invitation from Haifa University to talk to students about it via Zoom, the success of which led to further opportunities to speak about digital media and Holocaust studies. Each time, he says, the professors would ask him afterwards why he had abandoned the project. “I told them it’s because I got shamed and I don’t think Holocaust organisations would ever approve of it. They told me just do it because they’re always going to be offended by something. That brought back the confidence to do it again.”

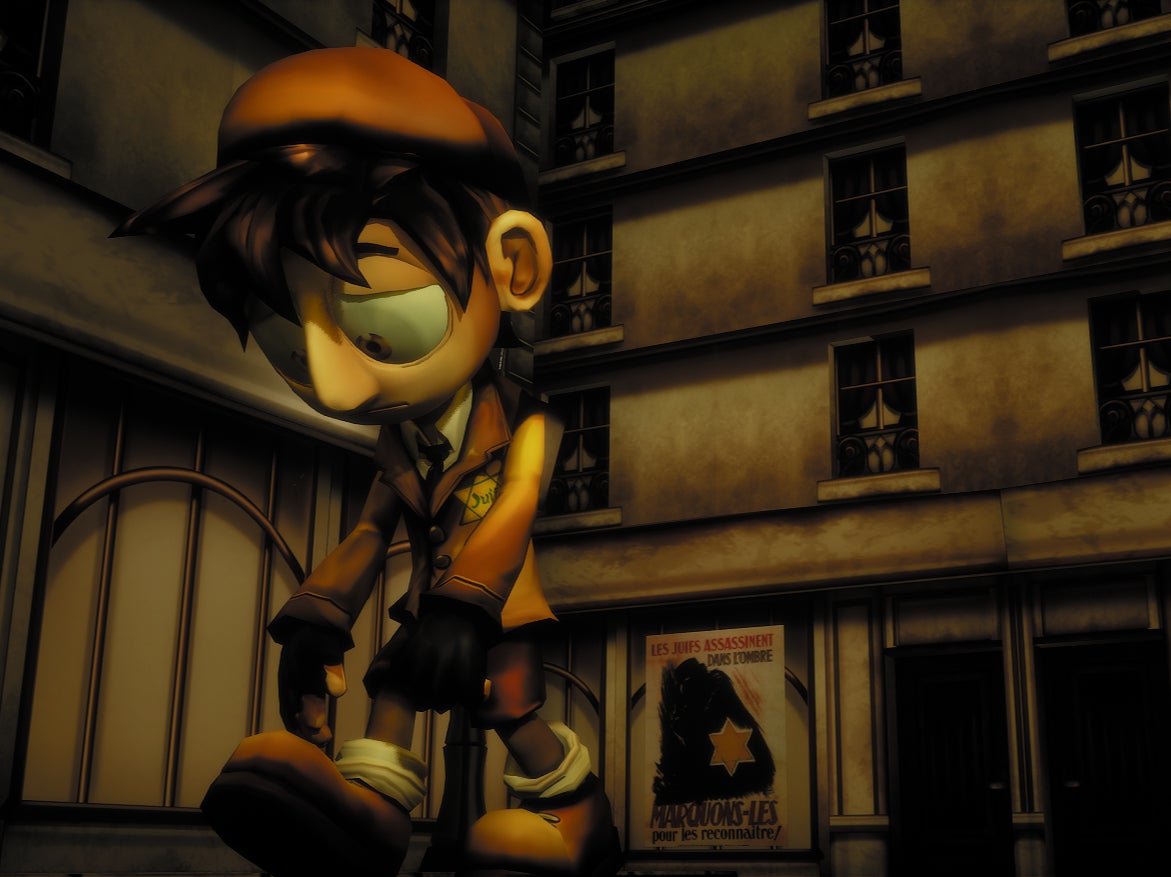

Whereas the first version was being designed to run on the Nintendo DS handheld console, the new one will initially appear on Microsoft’s Xbox. Starting virtually from scratch, Bernard deepened his research, drawing on multiple survivor testimonies, and enlisted a woman who had survived the Holocaust in France as a child to collaborate with him on the first draft of the script. The game now focuses on a working-class family of Polish Jews comprised of Bloomer, her husband Moses, and their son Samuel, and a non-Jewish friend called Maria, all of whom are playable characters.

Video games were going to tackle the Holocaust, no matter if we like it or not. So, my thing is like, no matter if I fail or succeed in this, I would have opened up the door for other video game directors

As the game progresses, we will see how their lives are impacted by the introduction of increasingly restrictive anti-Jewish laws – players, like Jews at the time, aren’t given choices, because you “can’t win the Holocaust” – and the complicity and indifference of ordinary French citizens, leading to the infamous Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup of foreign Jewish families in Paris, on 16 and 17 July 1942, by French police and gendarmes. “Most people, when they think of the Holocaust, they think Nazis,” says Bernard, “but everyday French policemen did that. I’m French, and I love France, but I think loving your country also means calling out your country when they do f***ed-up s***, because you want it to be better.”

Part of the effort of the game, he explains, is to make the player empathise with the characters, something that Schindler's List, for example, did so powerfully, and by doing so, take them on an emotional journey during which, “you will get to, in a way, experience antisemitism.” Most Jews already know what this feels like or know how to recognise it. His target audience, therefore, lies elsewhere.

“Someone who’s not Jewish or who hasn’t experienced antisemitism can’t understand it, and that’s why a lot of people don’t think it’s racism. I think playing the game allows them to understand that.” As this story was being written, Whoopi Goldberg was summarily suspended by the ABC network in America for two weeks for claiming that the Holocaust was not about race.

The contemporary relevance of this was thrown into sharp relief for Bernard in the spring of 2021, when the latest eruption of violence between Israel and Hamas resulted in an explosion of antisemitism online and in the streets. Social media became an “unhealthy place”, he says, because he saw industry peers, “start just being like, ‘F*** Zionists’.” As tensions heightened, a visibly Jewish boy living on his road was assaulted, and protesters carrying Israeli flags defaced with swastikas descended on the nearby LA Holocaust museum, chanting “Zionists are rapists”. Bernard and some friends went to see what was happening but quickly left because they felt unsafe. “We were like: ‘why are they doing this in front of the museum? Go to the Israeli embassy.’ I never thought in my lifetime that I would see anything like that.”

The rising torrent of antisemitism did not silence Bernard but made him more vocal about the Jewish part of himself, in large part, he believes, because of its erasure by his grandmother. This has not come without a cost, though. By highlighting antisemitism online and calling out lies such as Holocaust survivors went to Palestine to steal land, he opened himself up to abuse from people in the world of games media, as evidenced by tweets he sent me posted by a writer. “Some now like to call me the leading Zionist weirdo in the industry. Very nice, right?” he says wearily.

“I view the word Zionist, when a non-Jew says it, as something as bad as the N-word. I think it’s a word which needs to be kept out of some people’s mouths, because it can quickly descend into something vile. And it makes me really angry.”

The tide of hatred that was unleashed in spring 2021 caused Bernard to have a mental breakdown. “I felt very alone in the industry,” he says. On the other hand, it gave him a new perspective on the game. “Before, I was like I really need to tell this story that was important to me because it’s important to remember the Holocaust and the six million that died. But spring was when I realised that this is really important and really relevant to today.”

He is currently finessing the game, and has started filming interviews with French survivors, such as a woman who was hidden in a village, and another who recalled her family being told by a policeman that they were going to be deported. These will appear between gaming scenes as eyewitness commentary. He isn’t shooting the footage himself: “instead of putting survivors in a stressful environment around professionals outside their safe spaces, I’ve directly asked families to record them.”

When The Light in the Darkness is launched worldwide later this year, his hope is that it will engage hearts and minds in ways that traditional approaches to Holocaust education do not always achieve, and reach people who might otherwise not be interested. For this reason, he is giving it away for free, and has ambitions to offer it in different languages. “I'm even planning to translate it into Arabic and launch in places like Egypt, where antisemitism is really high.”

He has a number of ideal scenarios that he would like to see play out. One – which he admits is extreme and highly unlikely – is that a child with neo-Nazi parents will download the game and then, because it’s free, the adults won't check what they are playing, and the child will “get attached to the characters and actually start thinking differently, start thinking that the Holocaust was real, and maybe start doing their own research. Of course, that’s a dream scenario. But it’s not exactly the best pitch: ‘I want Nazis to play this game’,” he laughs.

Asked if it could be useful to an institution like the Neuberger Holocaust Centre, Panneton says often museums and education centres will provide visiting classes with survivor memoirs to take away in order to carry on learning. “I could hypothetically see a museum providing students with a download code for a digital experience like The Light in the Darkness,” he says, “if it met rigorous pedagogical standards and achieved its learning goals. It could also be a way of reaching communities that don’t have ready access to such a museum. Of course, we have to keep in mind the limitations of what technologies students may have at home to make the learning opportunity equitable and accessible.”

Bernard says he knew he was on to something 10 years ago with the project, despite all the heated opposition at the time, and it now appears that Holocaust organisations are finally catching up and listening.

“I just wish that they had come and talked to me back then,” he says, “because it was always going to happen. Video games were going to tackle the Holocaust, like it or not. So, my thing is, no matter if I fail or succeed in this, I would have opened up the door for other video game directors to finally be able to tell you stories. Just imagine if a video game company had $50m to actually make a game like this – it would be amazing!”

The Light in the Darkness will be released as a free download for the Xbox later this year

The Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre's Holocaust & Digital Memory discussion featuring Luc Bernard can be viewed here: https://virtualjcc.com/watch/holocaust-and-digital-memory-ihrd2022

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments