The return of a cherished European race or a ‘Bernie Ecclestone deal’? The French Grand Prix is back and splitting opinions

After 10 years off the calendar, France hosts this weekend's Grand Prix at its new home at Paul Ricard that rekindles memories of the Eighties when it was among the real greats

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If the traffic jams around the Circuit Paul Ricard yesterday are anything to go by, the return of the French Grand Prix has been welcomed by fans. Think Brands Hatch in the Eighties, and you won’t go far wrong.

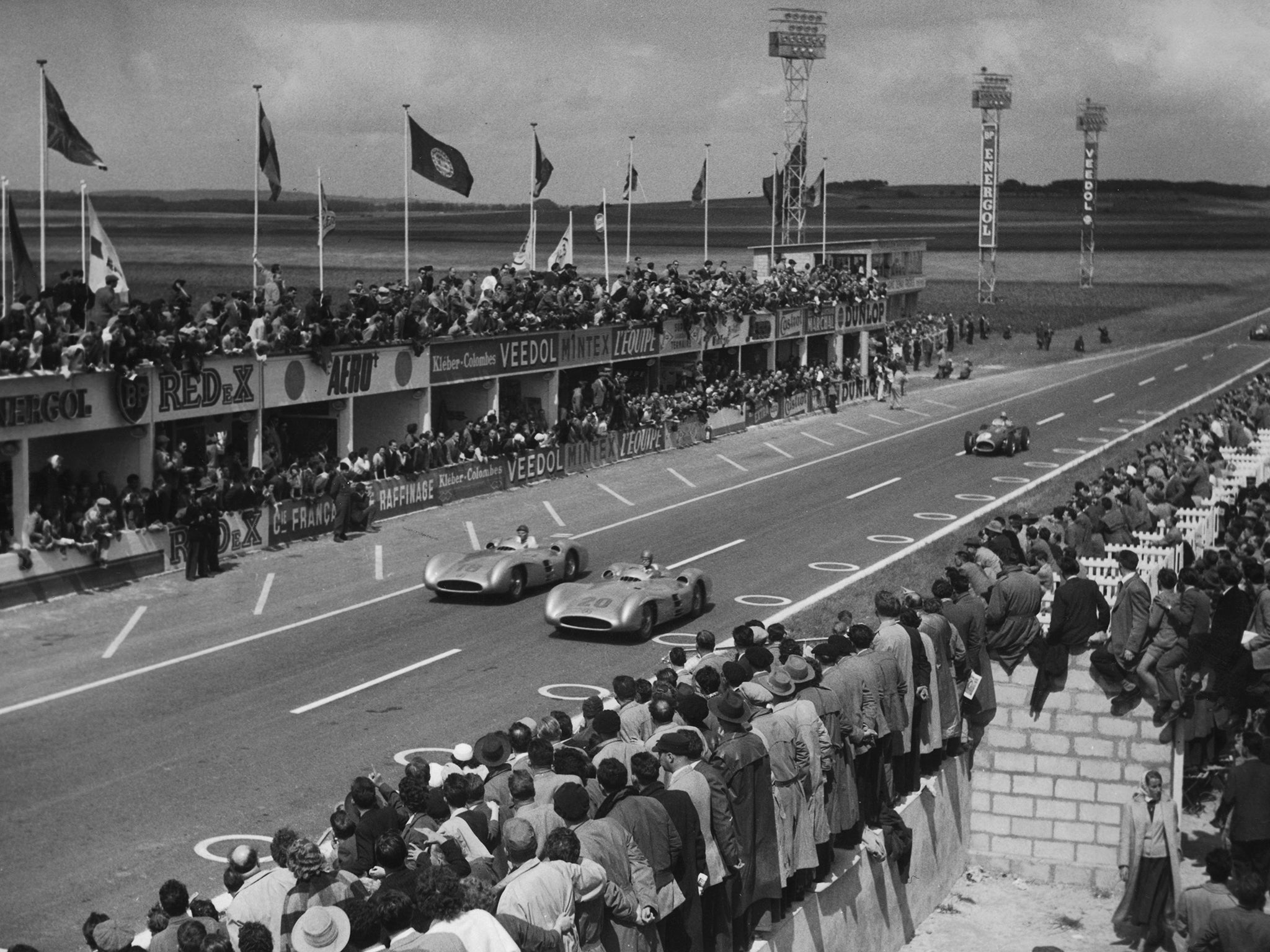

The race is a throwback. The British Grand Prix may have been the first race of the official World Championship back in 1950, but the first-ever grand prix was held in France over a road course at later-to-be-famous Le Mans in 1906, and resulted in victory for the Hungarian driver Ferenc Szisz, who appositely drove one of Marcel Renault’s new creations.

It was a regular fixture in the days when Formula 1 rarely ventured outside Europe, save for forays to north and central America, but it was a peripatetic event. Rheims, in the Champagne region, held the race in 1950 and ’51, then from 1953 to ’66; Rouen, in Normandy, took over in 1952, ’57, ’62, ’64 and ’68; for one hugely unpopular year, 1967, it was run in a car park track at Le Mans known as the Bugatti Circuit; Clermont-Ferrand in the Auvergne took over in 1965, ‘69 and ’70, before Paul Ricard Le Castellet became its home from 1971 to 1990, when it moved to its final resting place, Magny-Cours in central France.

By 2007 the race was in financial trouble before Bernie Ecclestone launched a rescue package with Prime Minister Francois Fillon that gave it the state-run track another year on life support before it disappeared from the calendar in 2009, amid much remorse. It was, after all, together with the races in Britain, Germany, Italy and Monaco, seen to be one of the heritage events that were officially protected. But times change. Plans for another major revamp of Magny-Cours foundered for economic reasons when Fillon was deposed by Jean-Marc Ayrault, and alternative proposals all came to nothing. More recently, former Nice Kawasaki dealer and 750 MotoGP rider Christian Estrosi, who raced against the likes of Giacomo Agostini, Barry Sheene and Phil Read, revived the idea of a French race after turning to politics and becoming the president of the regional authority of Provence and the Cote d'Azur.

In 2016 he agreed terms for a return to the then Ecclestone-owned Paul Ricard track for 2018, before Ecclestone was succeeded by new owner Liberty Media.

In many ways it is an apposite venue, for like Ecclestone, Paul Ricard himself was a maverick. He made his fortune brewing an eponymous absinthe-based pastis, the advertising of which was later banned by French authorities. Ricard was heavily into sponsorship in motorsports, bullfighting and petanque and for 1971 built his own track and named that after his aperitif, thereby bypassing the ban. He saw his new track as a resort, and today it includes a park, a kart track and other attractions.

“The most striking thing,” says writer Daniel Ortelli, the author of Circuit Paul Ricard: les seigneurs de la F1, “is that this is a brand new grand prix taking place on a mythical track. The mix of old and new is fascinating and evokes good memories for people who were here in their youth in the seventies and eighties, and have subsequently had their families.”

Today the track is owned by Slavica Ecclestone (Bernie’s former wife) and her sisters, and is rented to the organisers.

In many ways, the return of the French race is apposite. Renault are building up steadily to annex fourth place in the overall pecking order, as best of the rest behind Mercedes, Ferrari and Red Bull, and intend to keep going until they make it a top four and can recapture their past glories of the late Seventies, early Eighties and the mid-Noughties.

Romain Grosjean drives for the Haas team, and in Esteban Ocon, Force India have a young star who reminds many of the great Alain Prost, a six-time winner of his home race. Pierre Gasly, the Toro Rosso driver making a significant impression on his debut season in F1, hails from the northern city of Rouen.

In its heyday what used to be known as the Grand Prix de l'ACF (the Automobile Club de France) was an influential heavy hitter of an event that frequently set the trend and generated revisions in the sport’s regulations, establishing France firmly at the forefront.

Diehard fans welcome the return of a storied European race, at a time when F1 is set to venture even further afield as races in Miami and Vietnam are being mooted. But the revived French Grand Prix is seen as a ‘Bernie deal’ and therefore may have trouble fitting into Liberty Media’s new vision of races held in ‘destination’ cities. The current contract is for five years, in which €14m of public money will be invested annually based on the calculation that this will bring in €65m each year to the region while boosting employment.

But the infrastructure here, with all its ongoing problems of restricted geography, choked roads, intransigent gendarmes refusing access to those with the correct passes, and general frustration before you even arrive is a reminder of how things used to be in a bygone era.

Whether that will militate against its success remains to be seen, but there is underlying pressure for the sport’s oldest race to perform and deliver in a modern way if it is to justify a permanent fixture on an already crowded calendar.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments