Old writer, young wife: The life and times of the fifth and final Mrs Brink

Afrikaner novelist Andre Brink married Karina Szczurek when he was 71 and she was 29. They were together for 10 years before he died on a plane, beside her, high above Africa. She has just finished writing her memoir, in which she recounts her life with South Africa's most celebrated and controversial novelist. Andy Martin went to Cape Town to talk to her about life after Andre

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am sitting at André Brink’s desk. I am using André Brink’s computer to write this. I am sitting next to André Brink’s tough yet vulnerable young widow, Karina, at the old colonial-style Brink home in a leafy part of Cape Town. It was probably pure chance that she happened to mention ‘Rule 3010’ (from a poem by Finuala Dowling), ‘Don’t sleep with married men.’

‘Good rule,’ I said. ‘I sure as hell try not to.’

Last year, she had been speaking publicly about Flame in the Snow, the love letters between André Brink and the poet Ingrid Jonker, but people said they wanted her story. Now she has just finished writing her memoir with the title, The Fifth Mrs Brink. The story is a myth that happens to be real. Or, as Jeanne-Marie Jackson, a visiting professor from Johns Hopkins University, suggested to me, ''it’s more literary than literature''.

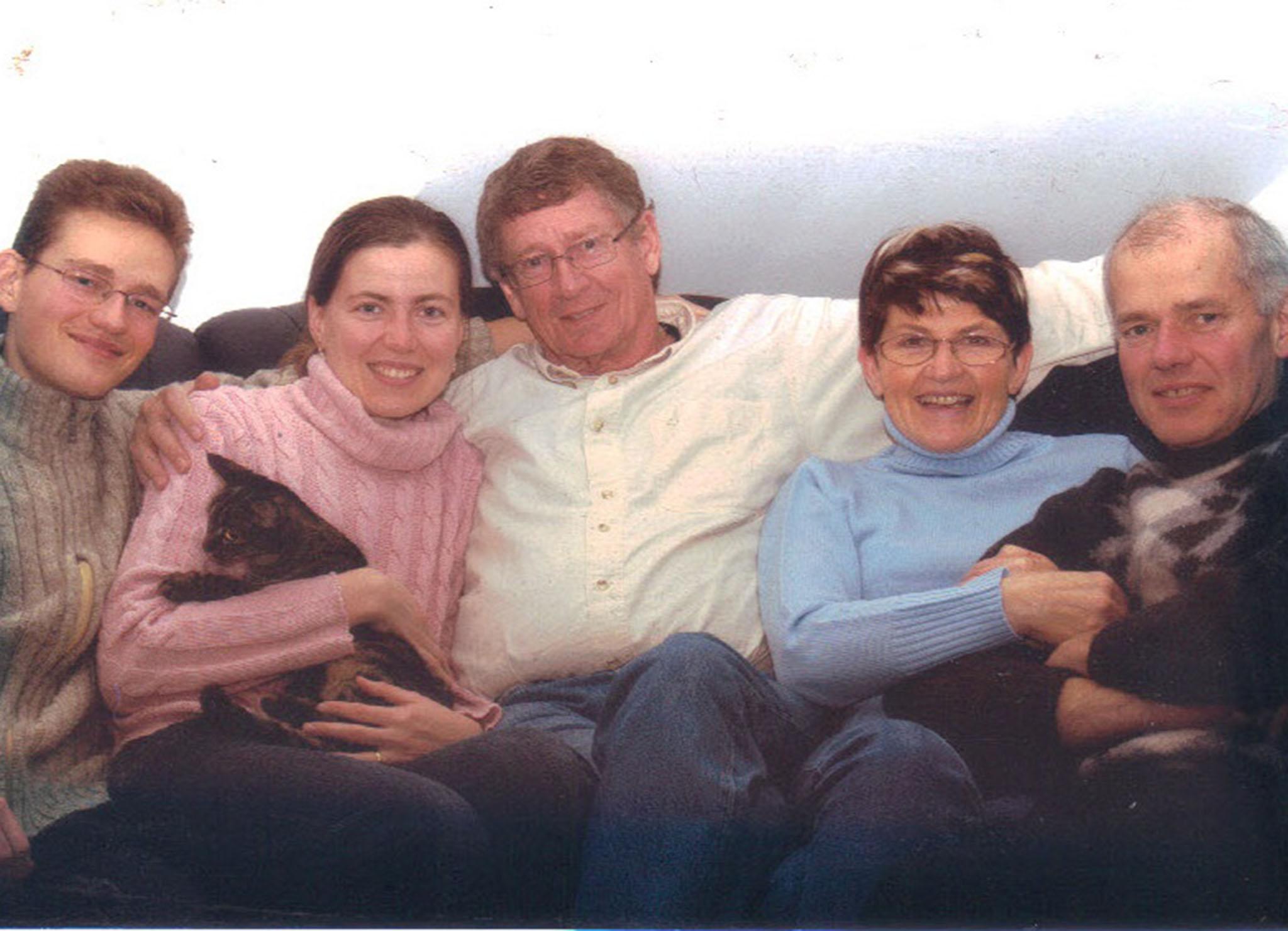

Old writer, young wife. There was a moment that dramatised the age difference. We were all sitting around a table and Leon de Kock, who is writing the authorised biography, The Love Song of André P Brink, was telling me about Brink’s adventures in Paris in 1963 and Karina chipped in, ‘'When my father was aged 6…’'

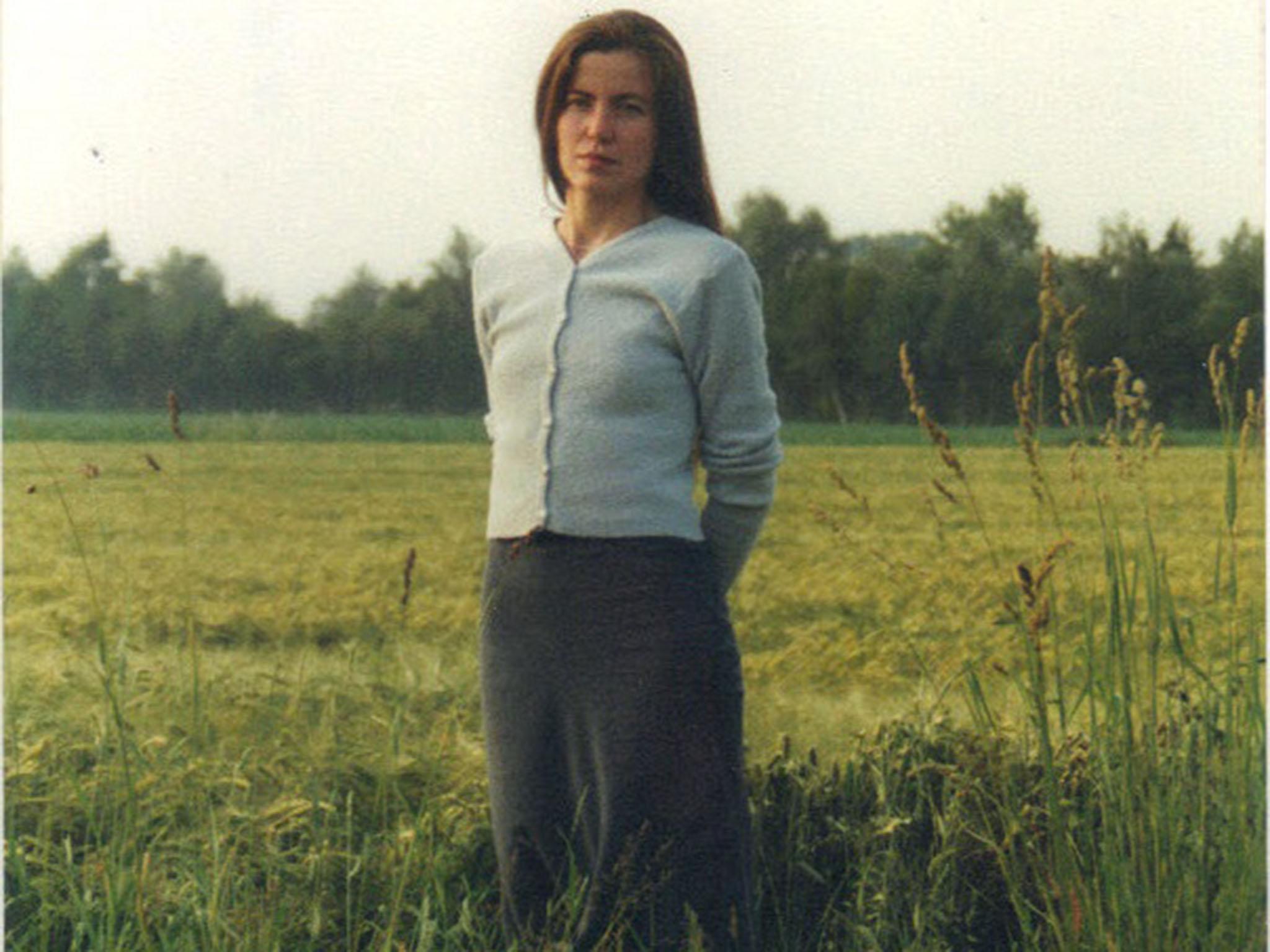

In 1977, Elvis Presley died; Star Wars came out; and Karina Magdalena Szczurek was born. Twenty-nine years later, in June 2006, Karina married André, aged 71. They had met in 2004 when the grad student went to collect the revered outlawed South African writer, author of A Dry White Season, at Vienna airport. He was wearing jeans and a leather jacket and didn’t look old. She had hair down to her waist, he had hair, short and wavy. She knew his work well and had once read his post-apartheid novel The Rights of Desire in a single sitting. Now she and the author began to fall in love on the train to Salzburg, corresponded from afar for the next nine months. He sent her Umberto Eco’s On Beauty. She wrote an essay about his An Instant in the Wind, a love story involving a runaway slave and a white woman, in which she wrote that ‘'whether something happens or not is not the issue, what is most important is the possibility and the faith in the chance of its happening''. A full-blown romance in Paris followed.

They had 10 years together, making a home in South Africa, but travelling all over the world to attend literary conferences, never apart. Then, in February 2015, on a plane high over Africa, André Brink dropped dead, aged 79. With Karina right there on the plane too, next to him. She watched him die. She was only 38. She had landed in what she called ‘'the foreign country of grief''.

Which is when I got to know her. It was not André Brink that brought us together but Jack Reacher, Lee Child’s immense fictional hero. Her husband had ceased to exist. Karina espoused Jack Reacher instead. He didn’t exist either, of course. And is therefore impossible to kill off. She wrote that '‘I reached out to Killing Floor [the first in the series] at a time in my life when everything had become difficult, including breathing. And to stay alive, I need reading as much as I need breathing.’' It turned out she and Reacher had a coffee habit in common, and a certain passion for numbers and chronology. Karina quickly started consuming Reachers the way she drank coffee. With an addictive fervour.

Her diary records that on 22 April she spent the entire morning in bed with Reacher and that ‘'I have fallen for this guy, big time''. The works of Lee Child came to fill the void her husband had left behind. Reacher was, in effect, a surrogate partner. A stand-in. One who would never die, on a plane, over Africa. Lee Child in New York got wind of his most evangelical convert in South Africa. He laughed at the idea of Reacher as a perfect husband (‘'He would keep running off and coming back home a mess. And he would never mow the lawn either.’') But in late 2015 he sent Karina a signed copy of Make Me and I threw in a copy of my book about the making of Make Me, Reacher Said Nothing.

Karina called it the ‘'Christmas miracle'’. Nine months later, I was in Cape Town for the Open Books festival and she was speaking to Lee Child in New York via video link and thanking him for saving her. There is a line in her novel, Invisible Others, where a character picks up a book ‘like a lifeboat after a shipwreck’.

Born in Poland, Karina became a refugee and a nomad, studying at different times in Salzburg and Aberystwyth, picking up languages as she went. She liked going to foreign countries. ‘'Nobody knows me here, I can do anything,'’ she thought to herself when she arrived in a new place. It was her postgraduate study of Nadine Gordimer that brought her into contact with André Brink. He had recently divorced his fourth wife. As his biographer Leon de Kock put it, ‘'he was on a life-long quest for marriageable romance''. He was also a ‘'fanatical narrativist'’.

His journals are a treasure-trove for the biographer. In 1968 alone he filled four 250-page notebooks with his neat, tight handwriting. Typing with one finger, this was the same year in which he broke two typewriters, and then ‘'he borrowed one from a woman and he broke that too''.

'‘The typewriter or the woman?'’ said Karina. She had a point. Sex, politics, and literature were intimately intertwined for Brink. ‘'Narrative was his meat and bread,'’ de Kock said. Likewise sexual love. ‘'By his own admission he had chronic sexual need.’' He would seek an outlet in the red light districts of Paris and Amsterdam. At school he was ‘'too intense, too fevered'’. Girls shied away from him and he ‘'married the first woman who would have him'’. But she was ‘'sexually withholding'’.

Then he found Ingrid Jonker. Jonker was his Brigitte Bardot, who embodied the brave new world of sexual freedom. His personal sexual revolution led him to turn his back on Grahamstown, where he taught at Rhodes University, colonial, provincial, Calvinist, racist, repressive, where even dancing was prohibited. He and his wife had to pray before sex. Then, with Jonker, ‘'everything explodes'’. Henceforth, he revolts against religion and apartheid and the whole South African system. His books are gloriously banned. ''We are dealing with a man who spent his entire life looking for romantic love in a loveless world,'’ said De Kock, and here he looked across the table at Karina. '‘And he died in its embrace.'’

The Fifth Mrs Brink gives us insights about Brink that perhaps only a partner could. The word chocolate appears three times on the first page of her manuscript by way of homage to the lifelong chocoholic that was Brink. He had a habit of ordering desserts in restaurants first. He was also a fan of jelly and custard, and something of an expert in making crème brûlée. As a kid, he once spent all his accumulated pocket money on a confectionery binge with some idea that he would thereby overcome desire. A few days later he was craving chocolate yet again. A valuable lesson about the nature of desire. Sublimation and self-repression never made any sense to him. Life was all about the fulfilment of desire, even if you might feel a little sick about it afterwards.

Another inescapable theme of the book is the twilight of the idol. The waning of Brink’s powers, physical and intellectual. He never really recovered from knee surgery and ended up in a wheelchair. Like the rest of us, he was slowly but surely losing his mind. In writing his last completed book Philida, he was struggling so much to keep track of his own plot – in two languages (Brink would always write in English and Afrikaans) – that they printed out hundreds of pages and spread it all out on the floor in the living room until it all made sense. Towards the end, he was in excruciating pain. When he died on the plane, it was like the death of the High Lama in Lost Horizon. It was ‘'semi-voluntary'’, a way of ‘'letting go'’.

''We did everything we wanted to do together,’' Karina reflects and recalls one incident which illuminates their married life. They had just returned from a trip to Switzerland. At 4am on a Sunday Karina woke up convinced that Rudolf had vanished. Rudolf is a two-inch high cuddly toy, ‘'half-dog, half-bear, half-guardian angel'’ that she carries around with her in a pouch she knitted herself. André spent the next two hours searching the house high and low without complaint before Rudolf turned up tucked into the side pocket of a case. Karina burst into tears, partly for the return of Rudolf but also because she realised, ‘'this man really loves me''.

One of the things I did in Cape Town was to go shark cage-diving. You are lowered into the water and the sharks circle around you eyeing you up. Being a young and attractive widow in Cape Town (or anywhere else), it occurred to me, is a little like that. Every now and then, if you stick a hand through the bars, you are going to get nibbled. In fact, let’s face it, this metaphor is unfair, because there are other predators a lot worse than sharks, and they pretend to be nice before coming in for the kill.

But I do not fear for Karina Szczurek. There is something of the Jack Reacher about her. She only looks fragile. Aged 12, back in Austria, she warned an older boy who was bullying her that he had better stop. He didn’t. So Karina punched him on the nose. The sight of blood '‘gave her endless satisfaction''. One of her favourite words is '‘integrity'’, which she finds exemplified in the world of André Brink, Lee Child, and George Lucas. She is wearing BB-8 ear-rings, modelled on the droid in the new Star Wars film. And she too wants to set the world to rights.

She is a great numbers freak. She is in love with 28. Conversely, she refuses to send out any article or book whose word count contains the number 17. She has to stir sugar in coffee 8 times and only 8. And she often has to wait to send an email at a particular hour. But above all she is self-confident enough to write The Fifth Mrs Brink. She doesn’t mind appearing to subordinate herself to her husband’s name, because (a) she doesn’t in fact feel the least bit subordinate and (b) she can then '‘surprise everyone by not being a Polish bimbo'’. She started a new novel, Fake Lives, on September 1.

I went back to André Brink’s desk before I left their house. There were three things on it that seemed to me to triangulate Brink’s life. One, a coaster emblazoned with a picture of Marilyn Monroe. Two, a miniature Déclaration des droits de l’homme, 1789; and, lastly, a copy of Albert Camus’ novel, The Outsider, where Brink has underlined the sentence in Camus’ own afterword, describing the book as '‘the story of a man who, without any heroic pretensions, agrees to die for the truth'’.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments