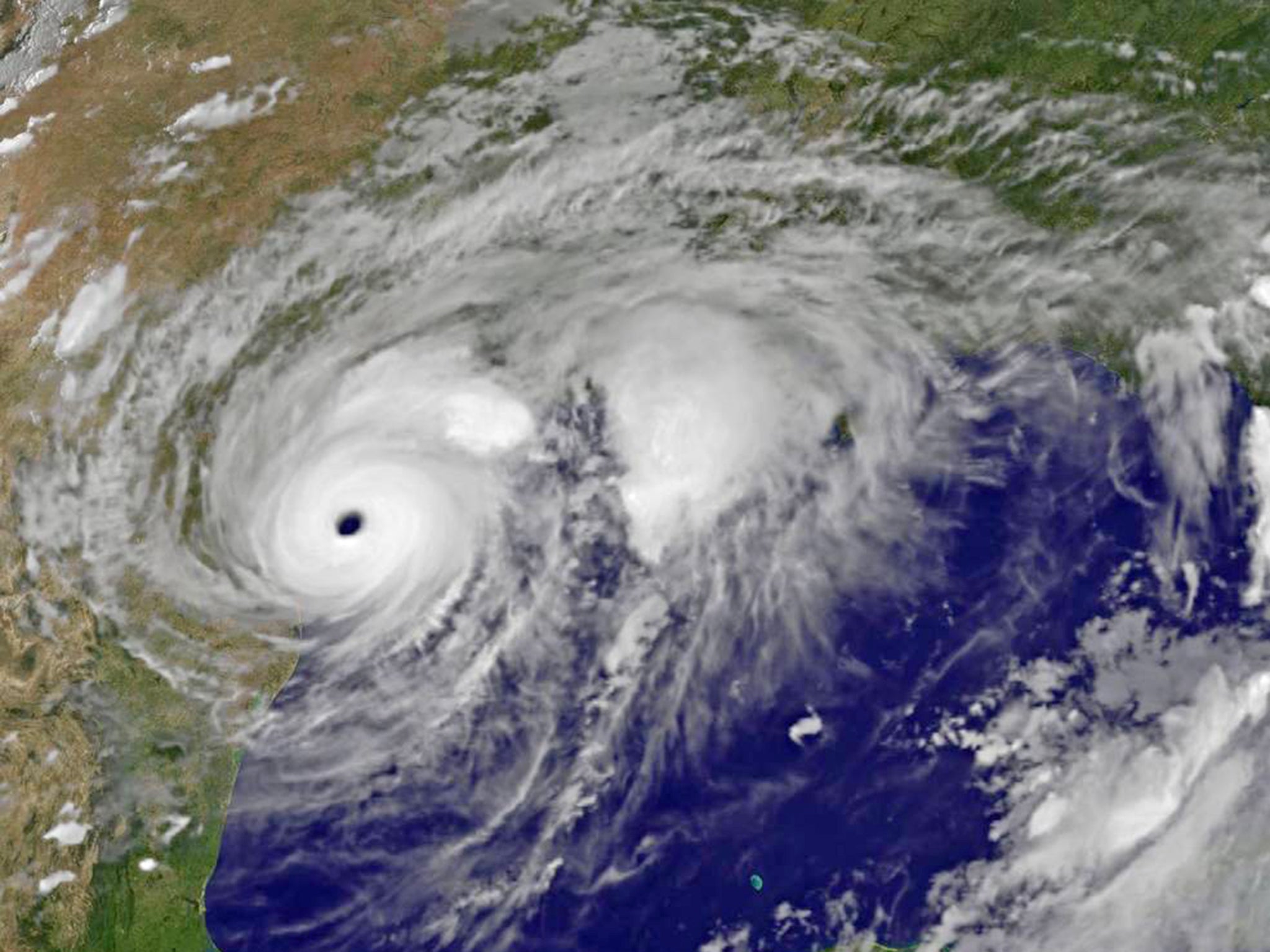

Dangerous tropical cyclones have slowed down because of global warming. Here’s why that’s a bad thing

Hurricanes are staying over given areas for longer period of time, increasing the risk of extreme rainfall and storm-induced damage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hurricanes and typhoons are slowing down due to rising global temperatures, meaning storms have more time to wreak havoc in the areas they strike.

Over the past 70 years – a period in which the planet warmed by 0.5C – the speed at which these enormous weather systems moved across the planet declined by around 10 per cent on average, according to new research.

This effect was particularly pronounced in the northern hemisphere, and is caused by the weakening of winds that drive their movement across the planet.

The “stalling” of these storms – known collectively as tropical cyclones – was on shocking display during Hurricane Harvey.

Dubbed “the hurricane that refused to leave”, the enormous storm which devastated Texas towards the end of 2017 dumped 50 inches (127cm) of rain on Houston over just five days.

Not only were 89 people killed by the cyclone, the ensuing flooding displaced 30,000 people and damaged or destroyed over 200,000 homes and businesses.

According to Dr James Kossin, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration researcher behind the study, as little as a 10 per cent slowdown in tropical cyclones could double future rainfall and flooding impacts.

These results were published in the journal Nature.

Dr Kossin described his findings, which add to existing evidence that climate change is increasing the likelihood and severity of natural disasters, as being “of great importance to society”.

Tropical cyclones already rank among the most deadly and most expensive of natural disasters.

Not only do their strong winds cause widespread destruction, the associated rainfall and storm surges add to the chaos by triggering floods and mudslides.

The longer a cyclone lingers over a particular region, the more damage it will inflict in that area.

“Tropical cyclones over land have slowed down 20 per cent in the Atlantic, 30 per cent in the northwestern Pacific, and 19 per cent in the Australian region,” said Dr Kossin.

“These trends are almost certainly increasing local rainfall totals and freshwater flooding, which is associated with very high mortality risk.”

Findings presented at the American Geophysical Union meeting in December found that global warming increased Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall by nearly 20 per cent.

Increasing temperatures boost the capacity of the atmosphere to hold water vapour, which in turn leads to higher rainfall.

Stalling storms resulting from higher temperatures disturbing the Earth’s atmospheric circulation will likely exacerbate this effect.

“The observed 10 per cent global slowdown occurred in a period when the planet warmed by 0.5C, but this does not provide a true measure of climate sensitivity, and more study is needed to determine how much more slowing will occur with continued warming,” said Dr Kossin.

“Still, it’s entirely plausible that local rainfall increases could actually be dominated by this slowdown rather than the expected rain-rate increases due to global warming,” Kossin remarks.

Until relatively recently, the link between global warming and natural disasters was not clear-cut, but better understanding and data availability has allowed scientists to make a strong case for this link.

According to Richard Black, director of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, an influx of studies from the past two years shows that “climate change is affecting heatwaves, droughts and rainfall right now”.

In a commentary on Dr Kossin’s research, Dr Christina Patricola from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory noted that “to strengthen the resilience of coastal and island communities to tropical cyclones, it is crucial to quantify and understand variability and change”.

“Kossin’s work paves the way towards developing this understanding.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments