Stop the Illegal Wildlife Trade: How pangolins became the ultimate luxury good

We are working with conservation charity Space for Giants to protect wildlife at risk from poachers due to the conservation funding crisis caused by Covid-19. Help is desperately needed to support wildlife rangers, local communities and law enforcement personnel to prevent wildlife crime. Donate to help Stop the Illegal Wildlife Trade here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How would you spend £340 ($450)? It’s a lot of money – enough for a haute couture purse from Yves Saint Laurent. It is also the market rate for a kilogram of scales from the world’s most trafficked animal.

The story of how the trade of pangolin scales became one of the most profitable illegal businesses in Africa is one that unfolds alongside the globalisation of crime and the increased Asian presence in Africa.

In the first part of this series, the conditions that forced destitute locals to poach pangolins were examined. But what happens afterwards? And what are the sophisticated networks behind this illegal trade that deliver these animal parts to consumers halfway across the world?

“Pangolin scales are trafficked more like drugs than ivory,” explains Steve Galster of non-governmental organisation Freeland. “[With ivory], buyers want a full tusk. You can move scales in different quantities, disguise them as fish scales, put them in canvas bags.”

“They can make their way over long distances without degrading from dampness, unlike cocaine.”

Based in Bangkok, Freeland seeks to combat international wildlife trafficking and human slavery. It is also part of the EndPandemics alliance of NGOs that are campaigning to “address the root cause of all zoonotic outbreaks – the wildlife trade and destruction of wild habitats”.

Asian demand for pangolin parts has quickly outpaced potential supply from Asian pangolin populations. The Zoological Socety of London lists the four Asian pangolin species – Chinese, Sunda, Philippine and Indian – as “critically endangered” or “endangered”.

“The African trade in pangolins has grown exponentially in recent years, pretty much because the four Asian species have been decimated,” says Professor Ray Jansen from the African Pangolin Working Group.

African pangolins now form a large proportion of the scales that reach consumer populations in China and Vietnam. Jansen believes that this change has only taken hold in the last four years. Before, pangolins were poached in Africa for their meat but the scales were largely seen as a waste product.

“You used to see piles of scales lying openly in ‘chop shops’ and bushmeat markets,” he says. Asian expat workers, who now number over 1 million in 54 African countries, came across them in markets and realised their value. “Four years ago, they went from a waste product to an expensive commodity. It was a whole new form of income for African people.

The trade has since been turned on its head, with the shimmering keratin scales now eclipsing the meat as a commodity. According to Freeland, 97 tonnes of pangolin scales were recorded to have left the African continent – the equivalent of about 150,000 pangolins. “It’s incomprehensible,” Jansen says.

As pangolin numbers dwindled in China, India and southeast Asia, criminal syndicates began to look to the African market. According to Freeland, Vietnamese organised crime leads the procurement of scales in Africa, with the implicit consent of bureaucrats and the military in those countries.

“They’re running the black-market FedEx, moving stuff from A to Z,” Galster says. And it’s not just pangolin scales that these gangs run. “They’re offering coke, drugs, anything. The Vietnamese sent their own sourcing agents to African countries, where they would set up and control the trade. The Nigerian gangs that control the cocaine trade coming out of Africa and into southeast Asia are also involved.”

Douglas Hendrie is the director of counter-wildlife-trafficking operations at the wildlife crime and investigations unit of Educating Nature Vietnam. In 2005, they created a national hotline for people to report wildlife crime in Vietnam. They now receive five new cases a day.

He tells The Independent of the last major seizure, on 31 March, that left Nigeria for Vietnam but was intercepted in Malaysia. Authorities found 6 tonnes of scales nestled between shipments – the equivalent of over 9,000 pangolins.

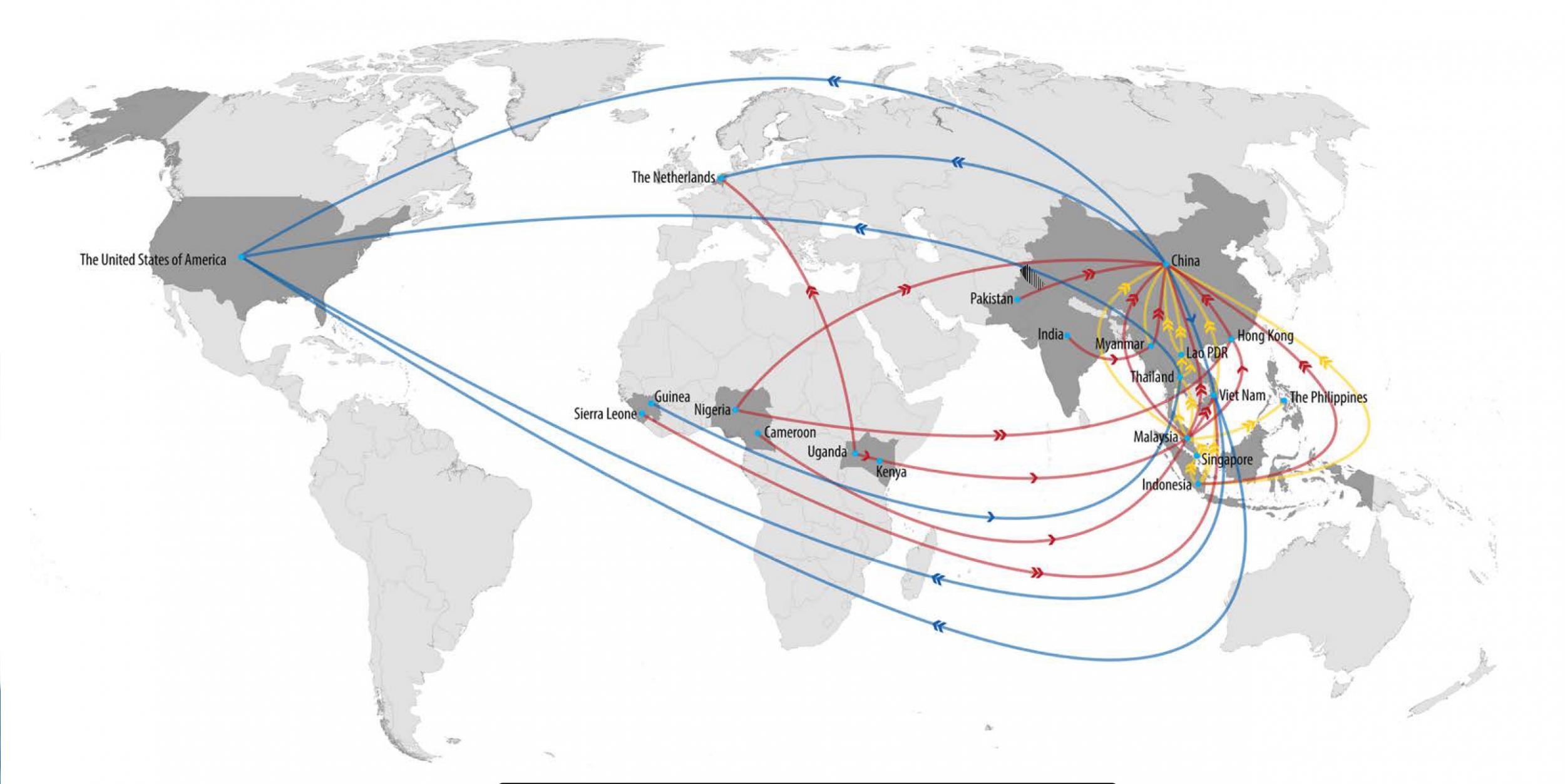

A report by the NGO Traffic from 2017 emphasises the global nature of the pangolin trade. “An average of 33 countries and territories were involved in international pangolin trafficking per year. Notably, an average of 27 new trade routes were identified each year, highlighting that wildlife trafficking occurs through a highly mobile trade network with constantly shifting trade routes.”

An unfortunate pangolin in Cameroon could find itself plucked out of a burrow by a local, who would then sell it to a middleman to pass on to an agent of a Nigerian crime syndicate in Yaounde.

Its body parts would be frozen and transported to a port in Nigeria, where a Vietnamese syndicate would organise for it to be shipped to Laos. From Laos, it would cross the "golden triangle" (the border region between Laos, Vietnam and China) into consumer markets in Vietnam and China.

“Huge, highly organised trafficking networks collect scales on the ground [in Africa],” says Professor Jansen. He says that Nigerian ports are responsible for 70 per cent of the African pangolin trade.

“It has evolved into a cat and mouse game,” explains Galster. “Phones seized from traffickers that reveal how they pick one lane or country one week.” Rival gangs are intensely competitive and often hostile. “Some seizures are just the result of one syndicate ratting on another,” he adds.

With the help of organisations such as Freeland, Asian customs forces are able to crack down on pangolin smuggling. Vietnamese and Malaysian officials have received specialised training. The Chinese and Hong Kongers have been “on the ball”, according to Galster. Syndicates have been forced to route shipments through Europe, notably Germany and the Netherlands.

Some scales end up in the United States too, where there is a persistent market for pangolin parts and other wildlife. In 2015, an investigation by the Humane Society International found “medicinal” products containing or likely to contain pangolin parts openly for sale online and on the high street.

Other shipments cross the border into China by oxen cart, but much of it goes through southeast Asia, Galster explains. “The Golden Triangle is one of many spots where smuggling occurs. In fact, the bulk of wildlife trafficking that occurs through Thailand happens in plain sight, passing through airports, seaports, and major highways, hidden under the cover of legal cargo.”

“Slowly but surely we’re starting to close routes down, but these guys find ways.”

Traffic’s report states that the top 10 countries involved with pangolin-trafficking incidents are China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia, the United States, Nigeria and Germany.

Since the start of the pandemic, global shipping has sharply declined and pangolin seizures along with it. Industry analysts expect that demand for container transport will drop by 30 per cent this year.

“This time last year we had tracked 70 tonnes of scales. Today we are only sitting on 10 tonnes”, says Jansen.

But wildlife experts do not think that poaching and wildlife crime levels have significantly changed in comparison with last year. Instead, pangolin parts are sitting in warehouses across Africa and southeast Asia.

According to Hendrie, Vietnam has only seen 10 seizures of live pangolins this year. “All our sources close to the trade are saying that Vietnam is ‘dry’ – even from ivory and tiger parts. Our African sources tell us that poaching is continuing, stockpiles are building up in Africa and waiting for the resumption of shipping.”

According to Freeland’s report, criminal syndicates will actively benefit from the continued threat of extinction to pangolins. “Organised criminal networks favour population reductions and even extinction of pangolins because it drives up the value of their stockpiled pangolin scales.”

In both China and Vietnam, pangolins are a traditional part of culture and alternative medicine. According to a 1938 edition of the British weekly scientific journal Nature, the scales have a range of applications: “Fresh scales are never used, but dried scales are roasted, ashed, cooked in oil, butter, vinegar, boy's urine, or roasted with earth or oyster shells, to cure a variety of ills. Amongst these are excessive nervousness and hysterical crying in children, women possessed by devils and ogres, malarial fever and deafness.”

Ground-up pangolin scales are also believed to promote menstruation and lactation in women. Meanwhile their meat, organs and foetuses are served as luxury dishes in Africa and southeast Asia.

Pangolins, like bats, are known to carry coronaviruses. One working theory of the outbreak of this coronavirus is that it came into the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan in a bat. The bat may then have passed it to a live pangolin at the market, which could have allowed the virus to make the jump to humans.

China made headlines in June by supposedly banning pangolin scales from use in traditional Chinese medicine, as well as increasing protections for its native pangolin populations. In February, China permanently banned consumption of wildlife, including pangolins.

Campaigners hailed these steps as a victory, but the Environmental Investigations Agency has cast doubt on whether pangolin scales have been completely removed as an ingredient in remedies. And what will happen to those tonnes of pangolin scales, waiting to enter the market?

Hendrie, who has worked in Vietnam since 1996, has seen the astronomical growth in prosperity of the country's middle classes. “Vietnam’s rise in wealth from 2000 to now is probably a repetition of what happened in China 20 years ago.”

Yet the bulk of consumers of pangolin meat, he explains, tend to be the older generations in Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi – for whom it remains a status symbol and luxury dish. “The kids who grew up now are more global citizens – internet savvy and globally valued. They grew up in a different Vietnam.”

There is hope that attitudes towards pangolins are changing across the world. Hendrie notes that “15 years ago the only exotic food readily available to wealthy Vietnamese was wildlife. Now in terms of the diversity of food available, it is no longer the only, limited choice”.

“We used to say – boy, if we could open up a franchise of Indian restaurants across Vietnam, we could end the wildlife trade in one swoop."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments