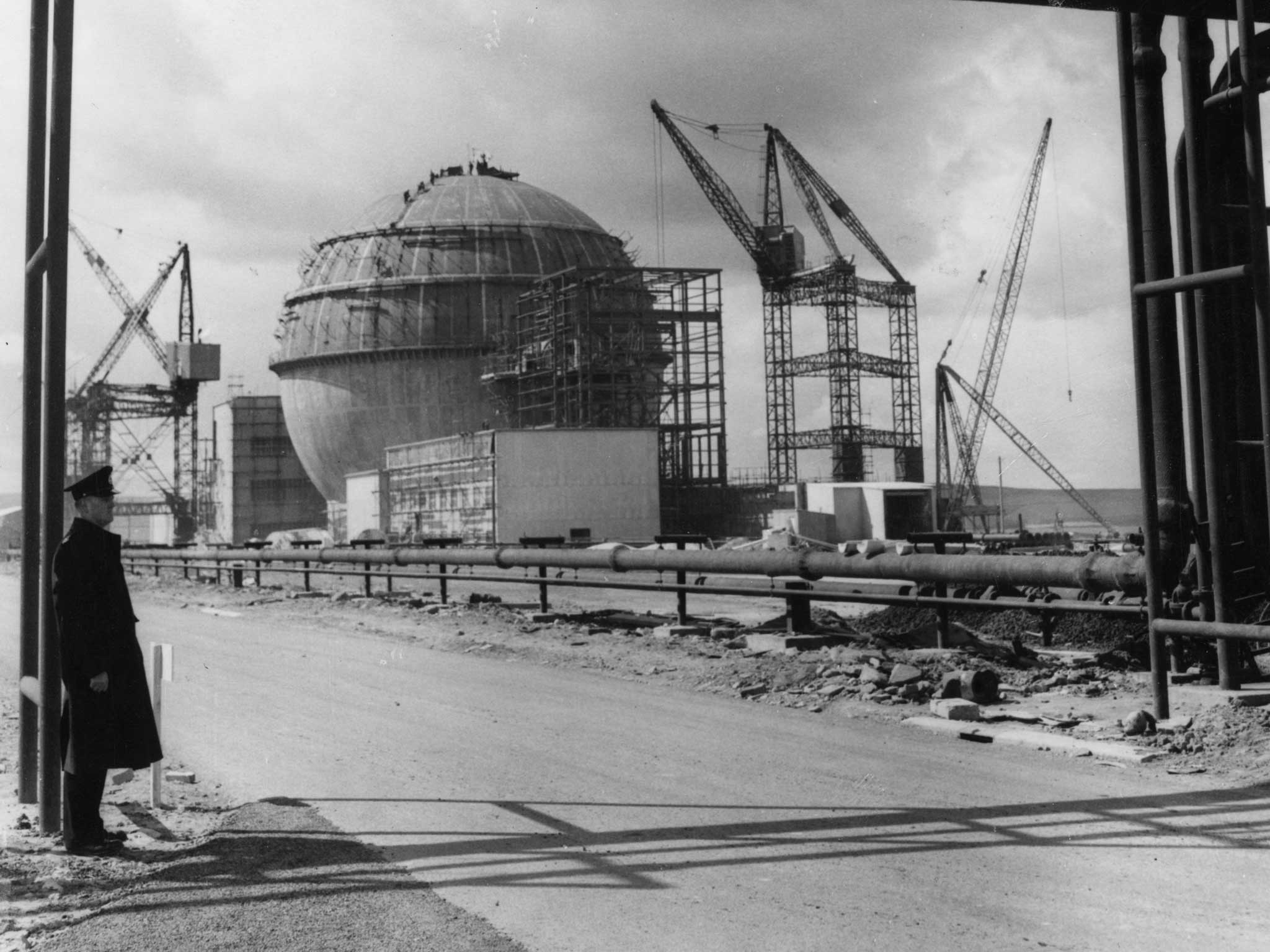

Nuclear power facility in Scotland will not be safe for other uses until the year 2333, report finds

Dounreay on Scottish north coast has been site of considerable radioactive leaks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 313 years’ time, 378 years after it first opened in 1955, and 339 years after it ceased operations in 1994, the 178-acre nuclear power facility site at Dounreay will be safe for other uses, a new report has stated.

Though the site on the north coast of Scotland was only home to functioning nuclear reactors for 39 years, the clean-up will take roughly ten times as long, with efforts already underway to clean up hazardous radioactive material.

The facility, near Thurso, was used by the government for research and testing of various types of nuclear reactors, including a "fast reactor" and those intended for use on nuclear submarines.

The first reactor at the site to provide power to the National Grid was the Dounreay Fast Reactor, which provided power between 1962 and 1977.

A second reactor also pumped power into the grid between 1975 and 1994.

A draft report from the government’s nuclear decommissioning authority states the site will only be ready for other uses after the year 2333.

Over the next two years, Dounreay Site Restoration Limited has said it will undertake assessments of “installations, current and future disposals, areas of land contamination, sub-surface structures and other discrete site conditions” to determine “credible options for the site end state”.

But the report’s “Roadmap for Mission Delivery”, charts an endpoint of 2333 for Scottish sites.

A process of demolition of buildings and waste removal is already underway at the site, which has previously been used to store dangerous radioactive material.

Part of the demolition process has involved the use of a remote controlled robot nicknamed the “Reactosaurus”, a 75-tonne device with radiation-proof cameras, and robotic arms which are able to reach 12 metres into the reactors where they can operate an array of size-reduction and handling tools, including diamond wire and disks and hydraulic shears.

One of the areas targeted for waste removal is a highly contaminated area called the Shaft.

In 1977, a catastrophic leak allowed seawater to flood a 65-metre-deep shaft which was packed full of radioactive waste as well as more than 2kg or sodium and potassium.

The water reacted violently with the sodium and potassium, throwing off the massive steel and concrete lids of the shaft, and littered the area with radioactive particles.

All radioactive waste is due to be removed from the Shaft by 2029, the report states.

The site also leaked radioactive fuel fragments into the sea in the local area for decades, between 1963 and 1984.

The dangerous pollution affected local beaches, the coastline and the seabed. Fishing has been banned within a two-kilometre radius of the plant since 1997.

Milled shards from the processing of irradiated plutonium and uranium, are roughly the size of grains of grains of sand. The most radioactive of the particles are believed to be potentially lethal if ingested. These small fragments are known to contain caesium-137, which has a half-life of 30 years, but they can also incorporate traces of plutonium-239, which has a half-life of over 24,000 years.

The Independent has contacted the NDA and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy for comment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments