Pregnant rhino could bring related subspecies back from brink of extinction

'The confirmation of this pregnancy through artificial insemination represents an historic event for our organisation but also a critical step in our effort to save the northern white rhino'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A southern white rhino’s pregnancy has raised hopes that her northern cousins can be saved from extinction.

Sudan – the last remaining male northern white rhino – died in March after suffering “age-related complications”, making extinction for his kind seem inevitable.

But after southern white Victoria was impregnated using artificial insemination at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, scientists think she could one day act as a surrogate for a new generation of northern whites.

Researchers at the zoo will watch closely to see if she can carry her calf to term over 16 to 18 months of gestation.

If she does, it is hoped that she could one day serve as a surrogate mother for the closely related northern white rhino.

After decades of decimation by poachers, there are only two remaining members of that species, both females, but neither Najin or Fatu, are capable of bearing calves.

Najin, age 28, has achilles tendons that could rupture under the weight of a pregnancy and, though younger, Fatu is barren because of a uterine infection.

However, researchers around the world are working on artificial reproduction techniques in an attempt to bring both species of rhino back from the brink.

Victoria is one of six female southern white rhinos at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research where testing is taking place to determine whether they are fit to be surrogate mothers.

She is the first to become pregnant.

If she gives birth, it is thought that they could carry northern white rhino embryos within the next decade, as scientists work to recreate northern white rhino embryos.

“The confirmation of this pregnancy through artificial insemination represents an historic event for our organisation but also a critical step in our effort to save the northern white rhino,” said Dr Barbara Durrant, director of reproductive sciences at the institute.

San Diego Zoo has the cell lines of 12 different northern white rhinos stored in freezing temperatures at its “Frozen Zoo”.

Scientists hope to use frozen skin cells from the dead northern white rhinos to transform them into stem cells and eventually sperm and eggs.

Then the scientists can use in vitro fertilisation to create embryos that can be put in the six female rhinos.

Meanwhile another team collaborating with Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, which is home to the last remaining northern whites, is working on a completely separate project to save the species.

“The process being worked in conjunction with Ol Pejeta will harvest eggs from the two remaining northern white females,” the conservancy’s spokeswoman Elodie Sampere told The Independent.

Working with Dvur Kralove zoo in the Czech Republic, scientists intend to use an Ol Pejeta southern white rhino as a surrogate for northern white rhino eggs.

Both projects face plenty of challenges. While Victoria is a healthy female, artificial insemination of rhinos in zoos has resulted in few births.

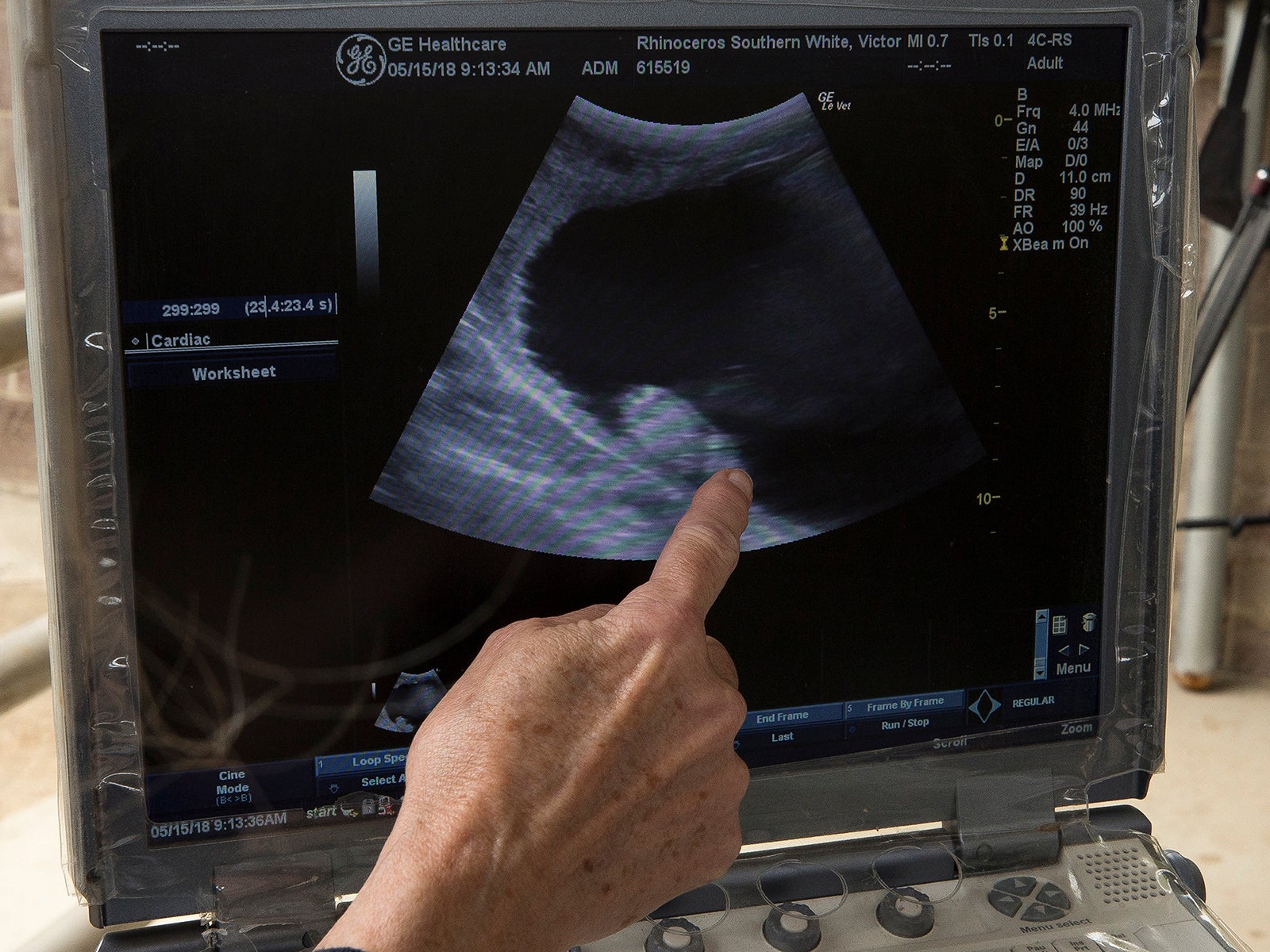

Scientists at the zoo will be perfecting artificial insemination techniques and embryo transfer techniques on her and her fellow San Diego females, which undergo weekly ultrasounds.

Dr Durrant recently spotted the beginning of tiny limbs of Victoria’s baby during her recent ultrasound. She is two months pregnant.

“We will know that they have proven themselves to be capable of carrying a foetus to term before we would risk putting a precious northern white rhino embryo into one of these southern white rhinos as a surrogate,” said Dr Durrant.

The ultimate goal – which could take decades – is to create a herd of five to 15 northern white rhinos that would be returned to their natural habitat in Africa.

Some groups have said in vitro fertilisation is being developed too late to save the northern white rhino, whose natural habitat in Chad, Sudan, Uganda, Congo and the Central African Republic has been ravaged by conflicts in the region.

They say the efforts should focus on other critically endangered species with a better chance at survival.

A recent collaborative effort between African governments and conservation organisations saw black rhinos reintroduced to Chad 50 years after poaching completely wiped them out.

Both black and white rhinos still face intense hunting pressure due to the demand for their precious horns, and that population will be guarded constantly by a special ranger unit to ensure their survival.

Upon the death of Sudan, wildlife manager at Kenya Wildlife Services Paul Masela described the sadness of watching a species go extinct in real time.

“I wouldn’t say it was a wake-up call because we saw it coming, and we should have done better,” he said.

Additional reporting by AP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments