Nasa data shows the world is running out of water

Scientists had long suspected humans were taxing underground water supplies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The world’s largest underground aquifers – a source of fresh water for hundreds of millions of people — are being depleted at alarming rates, according to new NASA satellite data that provides the most detailed picture yet of vital water reserves hidden under the Earth’s surface.

Twenty-one of the world’s 37 largest aquifers — in locations from India and China to the United States and France — have passed their sustainability tipping points, meaning more water was removed than replaced during the decade-long study period, researchers announced Tuesday. Thirteen aquifers declined at rates that put them into the most troubled category. The researchers said this indicated a long-term problem that’s likely to worsen as reliance on aquifers grows.

Scientists had long suspected that humans were taxing the world’s underground water supply, but the NASA data was the first detailed assessment to demonstrate that major aquifers were indeed struggling to keep pace with demands from agriculture, growing populations, and industries such as mining.

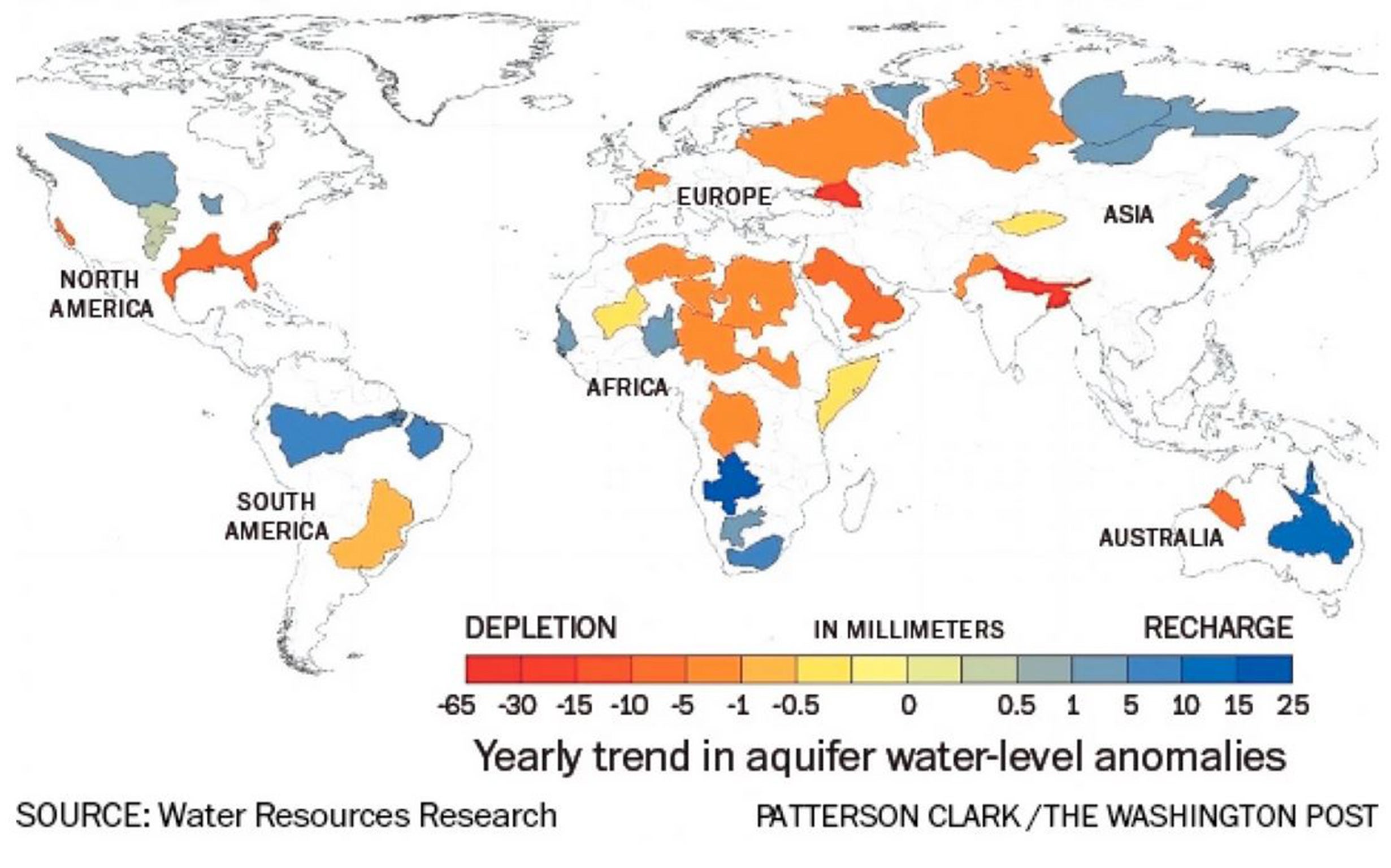

Satellite system flags stressed aquifers

More than half of Earth's 37 largest aquifers are being depleted, according to gravitational data from the GRACE satellite system.

“The situation is quite critical,” said Jay Famiglietti, senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and principal investigator of the University of California Irvine-led studies.

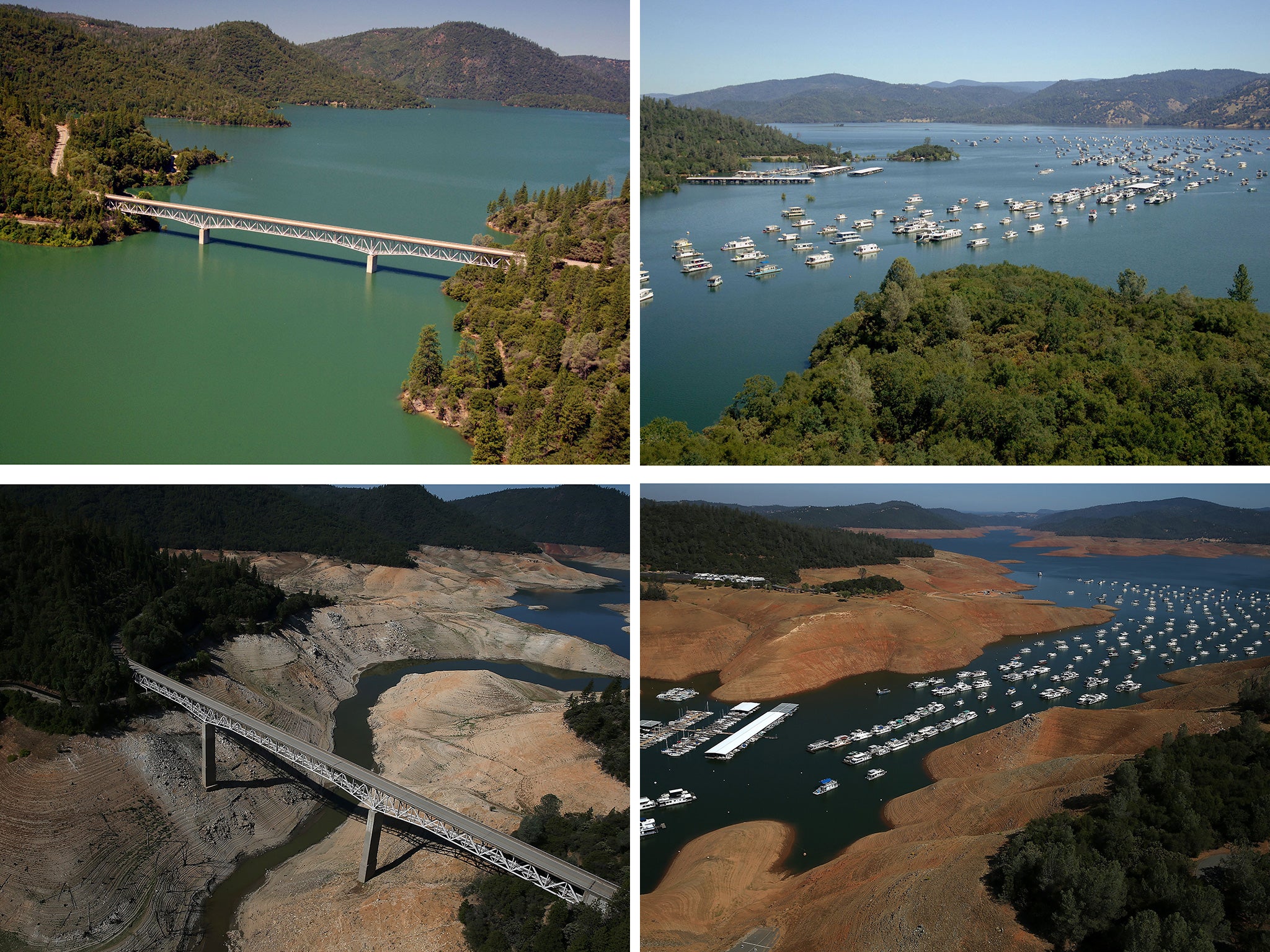

Underground aquifers supply 35 percent of the water used by humans worldwide. Demand is even greater in times of drought. Rain-starved California is currently tapping aquifers for 60 percent of its water use as its rivers and above-ground reservoirs dry up, a steep increase from the usual 40 percent. Some expect water from aquifers will account for virtually every drop of the state’s fresh water supply by year end.

The aquifers under the most stress are in poor, densely populated regions, such as northwest India, Pakistan and North Africa, where alternatives are limited and water shortages could quickly lead to instability.

The researchers used NASA’s GRACE satellites to take precise measurements of the world’s groundwater aquifers. The satellites detected subtle changes in the Earth’s gravitational pull, noting where the heavier weight of water exerted a greater pull on the orbiting spacecraft. Slight changes in aquifer water levels were charted over a decade, from 2003 to 2013.

“This has really been our first chance to see how these large reservoirs change over time,” said Gordon Grant, a research hydrologist at Oregon State University, who was not involved in the studies.

But the NASA satellites could not measure the total capacity of the aquifers. The size of these tucked-away water supplies remains something of a mystery. Still, the satellite data indicated that some aquifers may be much smaller than previously believed, and most estimates of aquifer reserves have “uncertainty ranges across orders of magnitude,” according to the research.

Aquifers can take thousands of years to fill up and only slowly recharge with water from snowmelt and rains. Now, as drilling for water has taken off across the globe, the hidden water reservoirs are being stressed.

“The water table is dropping all over the world,” Famiglietti said. “There’s not an infinite supply of water.”

The health of the world’s aquifers varied widely, mostly dependent on how they were used. In Australia, for example, the Canning Basin in the country’s western end had the third-highest rate of depletion in the world. But the Great Artesian Basin to the east was among the healthiest.

The difference, the studies found, is likely attributable to heavy gold and iron ore mining and oil and gas exploration near the Canning Basin. Those are water-intensive activities.

The world’s most stressed aquifer — defined as suffering rapid depletion with little or no sign of recharging — was the Arabian Aquifer, a water source used by more than 60 million people. That was followed by the Indus Basin in India and Pakistan, then the Murzuk-Djado Basin in Libya and Niger.

California's Central Valley Aquifer was the most troubled in the United States. It is being drained to irrigate farm fields, where drought has led to an explosion in the number of water wells being drilled. California only last year passed its first extensive groundwater regulations. But the new law could take two decades to take full effect.

©The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments