Soaring sea lion cancer linked to ocean dumping ground of 27,000 barrels of DDT off California

The exact location and extent of the toxic dumping ground close to Los Angeles was only discovered this week

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sea lions in California are dying from cancer at an unprecedented rate, potentially linked to thousands of toxic chemical barrels dumped in the Pacific Ocean decades ago.

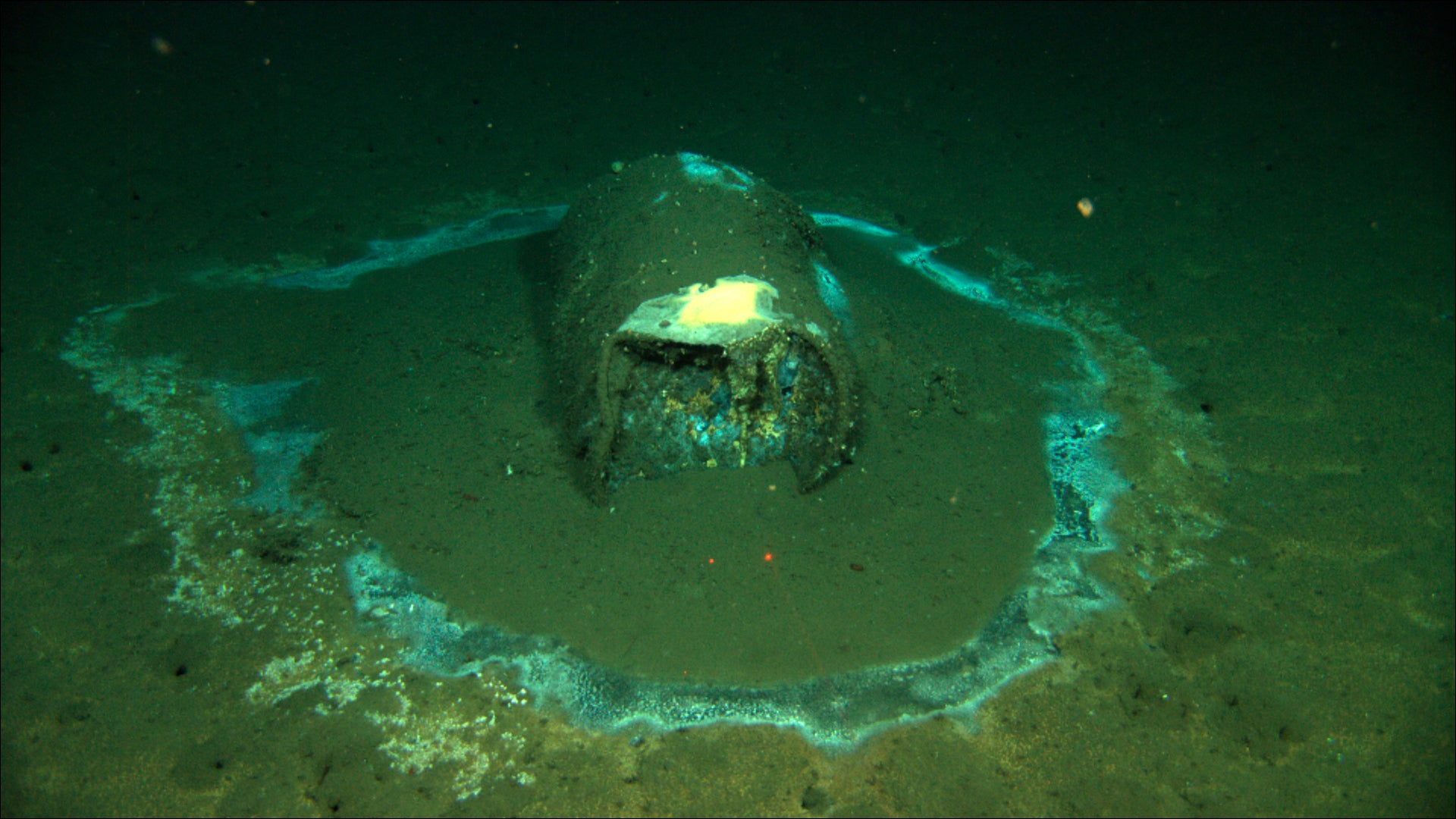

On Monday marine scientists revealed they had discovered what appears to be those barrels, possibly containing the toxic substance dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, known as DDT, off Southern California.

Some 27,345 “barrel-like” images were captured from a research vessel by a team from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California San Diego, who mapped more than 36,000 acres of seafloor between Santa Catalina Island and the Los Angeles coast.

It has long been suspected that a massive toxic dump was lurking beneath the surface and wreaking havoc on the health of marine life.

A recent study by the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito found that approximately one in five California adult sea lions have died from cancer. It develops from a herpes virus in sea lions, however not all animals who contracted herpes later died from cancer.

Dr Frances Gulland, senior scientist at the center and the paper’s lead author, told The Independent: “What the study showed is that animals with higher levels of contaminants develop cancer. The genetic markers we looked at were not significant in predisposing animals to cancer. It seems that early life exposure to contaminants makes them susceptible to the herpes-causing cancer, as distinct from being carrier animals.”

It is thought that the sea lions come into contact with DDT when they migrate to breeding sites on islands off Southern California. DDT travels through the food chain from microscopic creatures into fish which sea lions feed on. Over time, the toxin can build up in their blubber.

Sea lions with cancer either have to be euthanized or die from the aggressive disease which spreads around their spines and causes paralysis.

Studies have also linked DDT’s metabolized version, DDE, to egg-shell thinning in birds, including in brown pelicans and bald eagles. A 2015 study noted high amounts of DDT and other man-made chemicals in the blubber of bottlenose dolphins that died of natural causes.

Certain types of fish are so contaminated from the toxin that California authorities have warned fishermen not to consume their catches.

Dr Gulland said it had been assumed that little could be done to prevent sea lions from developing cancer because toxic waste had seeped into ocean sediment.

“But now with the barrels being discovered, you could prevent something from being a problem for hundreds of years,” she said. “Removing the barrels will be challenging but it's certainly possible.”

Resting deep in the ocean, the exact location and extent of the dumping ground was not known until now. Underwater drones using sonar technology captured high-resolution images of barrels resting 3,000 feet (900m) below the surface all along the steep seafloor that was surveyed.

“Unfortunately, the basin offshore Los Angeles had been a dumping ground for industrial waste for several decades, beginning in the 1930s. We found an extensive debris field in the wide area survey,” Eric Terrill, chief scientist of the expedition and director of the Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told AP.

The survey, conducted the survey from March 10-24 , provides “a wide-area map” of the barrels, though it will be up to others to confirm through sediment sampling that the containers hold DDT, Dr Terrill said.

It has been estimated between 350 and 700 tons of DDT were dumped in the area some 12 miles (20 km) from Los Angeles. The Palos Verdes Shelf off the coast is designated a “Superfund” - a toxic site on the US government list scheduled for clean-up - due to the DDT and PCB contamination.

DDT had been invented as a pesticide on the cusp of the Second World War, and was used to protect soldiers from malaria, typhus, and the other insect-borne human diseases. It was later widely used to spray agricultural crops and livestock, and even on beaches to prevent mosquitoes.

In 1972, DDT was banned by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) after it was classed as a possible human carcinogen, and linked to adverse impacts on wildlife and the environment.

The largest manufacturer of DDT in the US was Montrose Chemical Corporation, whose plant was located in Torrance, just outside of LA. From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, millions of pounds of the pesticide were discharged from the plant into the ocean.

Scientists conducted the survey following a Los Angeles Times report last year about evidence that DDT was dumped into the ocean. The Times reviewed shipping logs from a disposal company supporting Montrose, which showed 2,000 barrels of DDT-laced sludge were dumped in the deep ocean each month from 1947 to 1961 off Catalina, and other companies also dumped there until 1972.

Scientists started the search where University of California Santa Barbara professor David Valentine had discovered concentrated accumulations of DDT in the sediments and spotted 60 barrels about a decade ago.

While some of Montrose's hazardous waste flowed out to sea through the sewer system, the rest was poured into barrels and sailed ten to 15 miles offshore before being tossed overboard, a practice which was legal at the time.

Prof. Valentine earlier told CBS that while the company was supposed to dump the barrels in deep water, this wasn’t always the case. Some barrels were thrown into the water closer to shore while others were punctured to help them sink, allowing the toxic waste to seep out.

In 1990 the government sued over the toxic dump. After a decade-long battle the companies involved, including Montrose, paid out $140 million to be used in the clean-up of the Superfund site.

AP contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments