Stability in the Middle East now depends on how serious we are about tackling climate change

Countries without regular power and sufficient water are prone to shortages, droughts and crop failures, all of which foster insurgency

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Beyond the terrible conflicts in Syria and Yemen, and the continuing threat of a nuclear Iran, the Middle East is changing, and so is the west’s security relationship with it.

In the past, our predominant interests in the region were in counterterrorism and lucrative arms deals. The recent meeting between John Kerry, the US special presidential envoy for climate, and the UK’s own Cop26 president, Alok Sharma, demonstrated that the new common interest is climate change, and especially its link to security.

In government, I held both the energy and defence briefs, and the linkage became very clear to me. Countries without regular power and sufficient water were prone to shortages, droughts and crop failures that fostered instability and insurgency: man-made climate change was itself becoming a key driver of that instability.

The UK’s 2015 strategic defence review, which I oversaw, recognised this as a new and growing threat; last month’s integrated review promised sustained international cooperation to accelerate progress towards net-zero emissions and build global climate resilience.

Richer countries are affected, too. Stable security partners such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, both heavily dependent on hydrocarbon revenues, are now moving fast to develop projects that tackle climate change and help switch to more renewable sources of energy. This isn’t selflessness: they need new skilled, high-tech industries that can provide quality jobs for their young populations. Secure jobs and new modern industries will help safeguard the security partnerships on which the west relies.

My counterparts in the Obama administration, right up to the president himself, were very alive to the impact of climate change on the stability of the Middle East. President Obama directed his security agencies to consider the effect of a warming planet on all future doctrines, plans and strategies. After the hiatus of the Trump years, the Biden administration has now picked this up again. Holding a last-minute round table of this nature, in a nation considered one of America’s strongest security partners, is a subtle nod to the enhanced role that energy and climate will play in America’s future security agenda.

John Kerry was in the United Arab Emirates earlier this month, co-chairing a climate-change round table of Gulf nations. That underlined America’s future agenda. And its partners in the region are responding proactively. The UAE already has one of the region’s most ambitious emissions reduction plans: a cut of 23 per cent by 2030. Five years ago, they might have laid on a military inspection for John Kerry. This time, Dr Sultan al Jaber, his UAE counterpart, took him around the world’s largest solar park, Noor Abu Dhabi.

Across the region, other oil-dominated economies are following suit. Investment in solar panels and in other renewables is becoming as important as in military hardware. Countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE will be leading participants in this winter’s climate change conference in Glasgow.

The US has always been committed to the stability of the Middle East. Of course, the new nuclear talks with Iran in Vienna are important. But it is striking that the first formal engagement of senior officials of the Biden administration in the Middle East wasn’t about hard power at all. It shows how, for Joe Biden and Kerry and their teams, climate change and regional security are now two sides of the same coin.

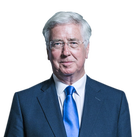

Michael Fallon is a British politician who served as secretary of state for defence from 2014 to 2017 and secretary of state for energy from 2013 to 2014

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments