The Big Question: Does nuclear power now provide the answer to Britain’s energy needs?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Because as The Independent reported yesterday four of the country’s leading green activists have overcome a lifetime’s opposition to warn of the dire consequences of not building more nuclear power stations.

Scientific evidence about the environmental impact of burning coal, gas and oil has overcome concerns about safety issues, the build-up of radioactive waste and the proliferation of nuclear weapons. So Stephen Tindale, a former director of Greenpace; Lord Chris Smith of Finsbury, the chairman of the Environment Agency; Mark Lynas, author of the Royal Society’s science book of the year; and Chris Goodall, a Green Party activist and prospective parliamentary candidate, are now all lobbying in favour of their erstwhile bete noir.

What nuclear capacity do we have at the moment?

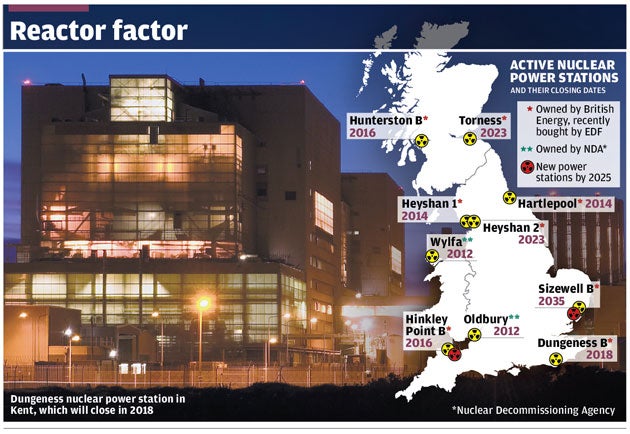

Nuclear power currently accounts for about a fifth of the UK’s electricity, compared with the 35 per cent from coal and 35 per cent from gas. There are 19 reactors in 10 different power stations across the country. But the fleet is ageing. The last two Magnox power stations, now under the control of the Nuclear Decommissioning Agency (NDA), have already had their lives extended once and will both be turned off by 2012 at the latest. Of the remaining eight nuclear plants – owned by British Energy (BE) – all except the one reactor at Sizewell in Suffolk are due to be shut down by 2023. BE is working on plans to extend lifespans, but at least two have already been extended once.

Why do we need more?

Partly to replace the obsolete nuclear capacity. Left to itself, the proportion of UK electricity provided by the nuclear sector will be down to single digits by 2018, and in 15 years only one reactor will remain in operation. But nuclear is not the only dwindling supply. Some eight gigawatts – equivalent to about six power stations – of coal-fired generating capacity will be out of action by 2015 as Europe’s clean-air directive bites and older facilities prove uneconomic to upgrade. Taken together, the UK needs to replace a third of its electricity generating capacity in the next 15 years. Even plans for seven gigawatts of new gas-fired capacity, expected by 2015, and another five gigawatts recently given the go-ahead by the Government, will not be enough as estimates put energy demand ballooning by anything up to 20 per cent in the coming decade.

How does nuclear fit in with the UK’s overall energy strategy?

Very well. Not only is it able to produce massive amounts of power with no carbon emissions. It is also entirely secure, increasingly important as North Sea oil and gas reserves decline. With the vast majority of the world’s gas held by Russia, Qatar and Iran, we may be left dangerously exposed to the vicissitudes of geopolitics – as the flare-up between Russia and Ukraine last month amply proved.

A private sector-led “nuclear renaissance” is only part of the solution. Targets for renewable energy are being ramped up. Investments in fossil fuels are also continuing. As-yet-unproven carbon capture and storage systems will be central to meeting green criticisms such as those levelled at the controversial coal-fired plant proposed for Kingsnorth in Kent.

What are the plans for nuclear?

So far, EDF is making the running. The French energy giant spent £12.5bn buying British Energy, giving it eight nuclear power stations and one coal-fired facility. It is also committed to building four new nuclear reactors by 2025, two at Hinkley Point in Somerset and two at Sizewell in Suffolk. The first, at Hinkley, could be up and running as early as 2017. The other company with specific plans is E.ON, the German utility. Last month, the company announced it was teaming up with RWE, another German group, to spend £10bn building five reactors, or at least two new power stations, over the next 15 years. The plan is for the first to be online by 2020, the other soon after.

What is it worth?

Lots. Both in terms of the local economy, and in terms of the global market, nuclear is a big prize. Potential suppliers from all over the world are lining up for a piece of the action. GDF Suez and Iberdrola, from France and Spain respectively, are making moves to take on E.ON and EDF. Rolls-Royce, Balfour Beatty, the builder, and Areva, the French reactor maker, say they expect to create up 15,000 jobs in the sector between them. But the UK is just the start.

Nuclear power is finding favour across the world, and as the havoc wrought by the financial crisis spreads ever wider, the energy sector is a rare case of relative stability. The global civil nuclear industry is currently worth about £30bn a year. But it is expected to swell to £50bn in 15 years’ time. Any company which can prove itself in one place will have the potential to sell its expertise across the world – with much to gain for its home economy.

Is it a big deal that the Green have changed?

Yes and no. Symbolically it is hugely important. Plans for new reactors are still expected to raise hackles but the Green movement’s acknowledgement of nuclear as the lesser of two evils will take away some of the sting. Ironically, it is the environmental agenda that made the economics of commercial nuclear expansion work. Regardless of moral reservations, the cost of nuclear power stations compared with their gas and coal-fired cousins has always been a major factor. But the introduction of a carbon emissions trading mechanism has forced fossil fuel plants to pay for their environmental impact, and the predictable income for nuclear plants provides much-needed clarity for private sector investors.

Are the Greens’ concerns now all answered?

No. There are two main environmental complaints about nuclear, and only one has changed. On the question of safety, accidents such as that at Chernobyl in 1986 caused massive image problems. But accidents are increasingly rare thanks to technical improvements and tight regulations.

The other big issue is waste. While the processing of spent fuel has also come a long way from the early days of the industry, critics emphasise that the basic process is still the same. No way to neutralise defunct fuel rods has yet been found, and the only solution is still to bury them. There are concerns that global expansion will not only boosting uranium mining to destructive levels, but that safe storage locations will also be exhausted.

What happens now?

Before anything can actually be built, the Health and Safety Executive must complete its investigation of the two next-generation reactor technologies that will go into any new plants. The planning process is the other big potential cause of delay. Even the reform of the system and creation of a central Planning Inspectorate to speed through national infrastructure schemes may not help.

But things are moving. EDF already has its plans in hand, and the NDA is in the process of auctioning off sites adjacent to three existing facilities – at Wylfa in Anglesey, Bradwell in Essex and Oldbury in Gloucestershire – for the purposes of new nuclear. The finally auction itself is due in April, with all the big names expected to be involved in the bidding. Once those three sites are sold, the NDA will start the process for another piece of land at Sellafield.

So is nuclear expansion an unalloyed good?

Yes

*In an increasingly power-hungry world, the generation capacity of nuclear is potentially enormous

*Nuclear reactors are the best way to produce lots of electricity, reliably, with no carbon emissions

*Except for the purchase of uranium, nuclear power stations offer absolute security of supply

No

*Safety records may be far better than they were in the early days, but accidents can always happen

*Despite technical advances, digging a hole is still the only way to get rid of spent fuel rods

*More countries, buying more uranium, means more mining and more chance of nuclear proliferation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments