Human-driven climate change is shrinking snowpack in US with devastating consequences, study says

Thanks to a new study, we are ‘virtually certain’ human-driven climate change is decreasing snowpack in the southwest and northeast US

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Climate change is causing the US to lose so much snowpack, a new study finds, that it could devastate water access and destroy winter-reliant industries.

Snowpack — or snow that stores water and releases it as it melts during the spring and summer — is an essential source of water for many regional systems, and fuels snow-based economics like skiing. Until now, researchers have struggled to definitively link the well-documented loss of snowpack in certain areas to human-driven climate change.

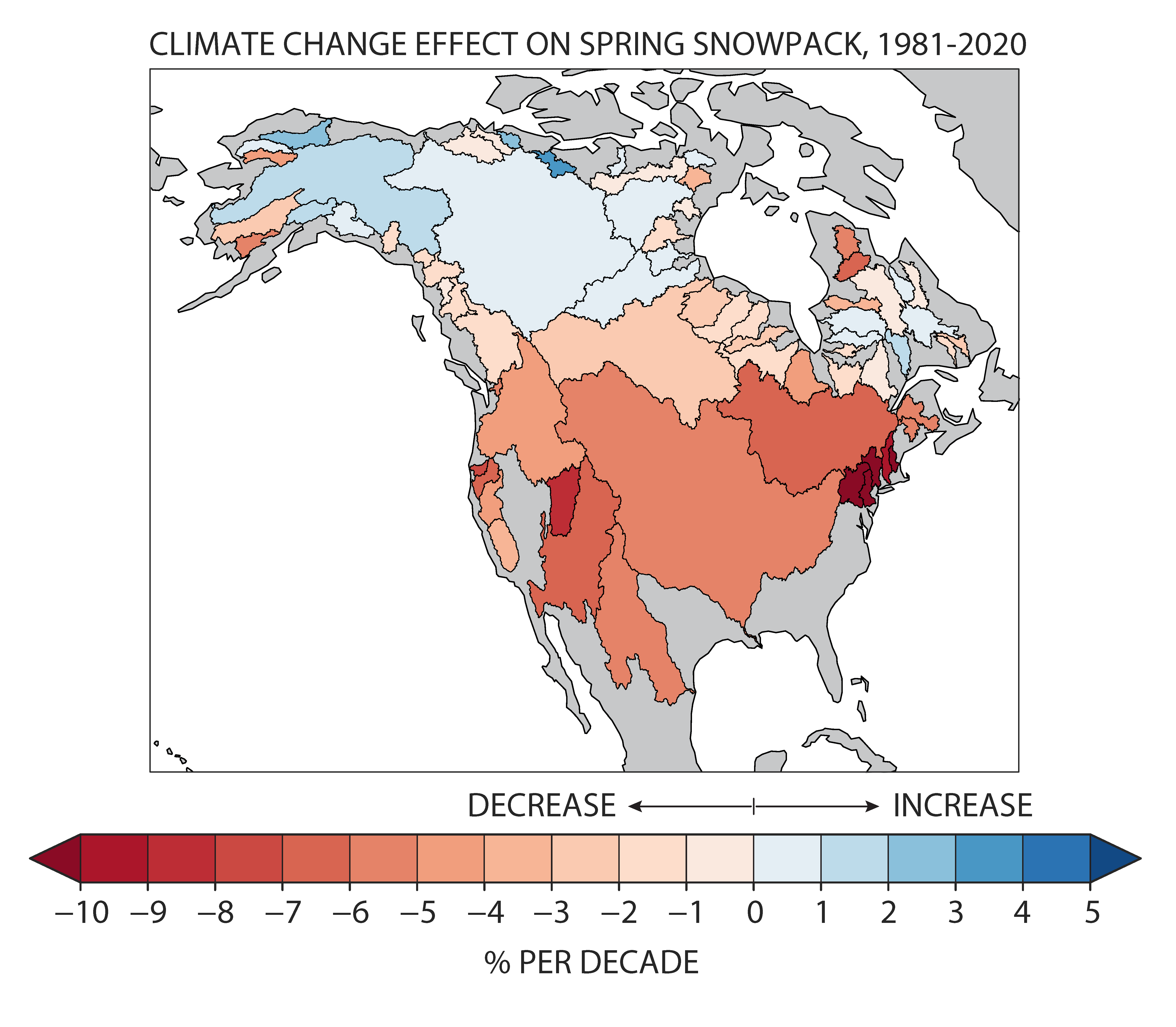

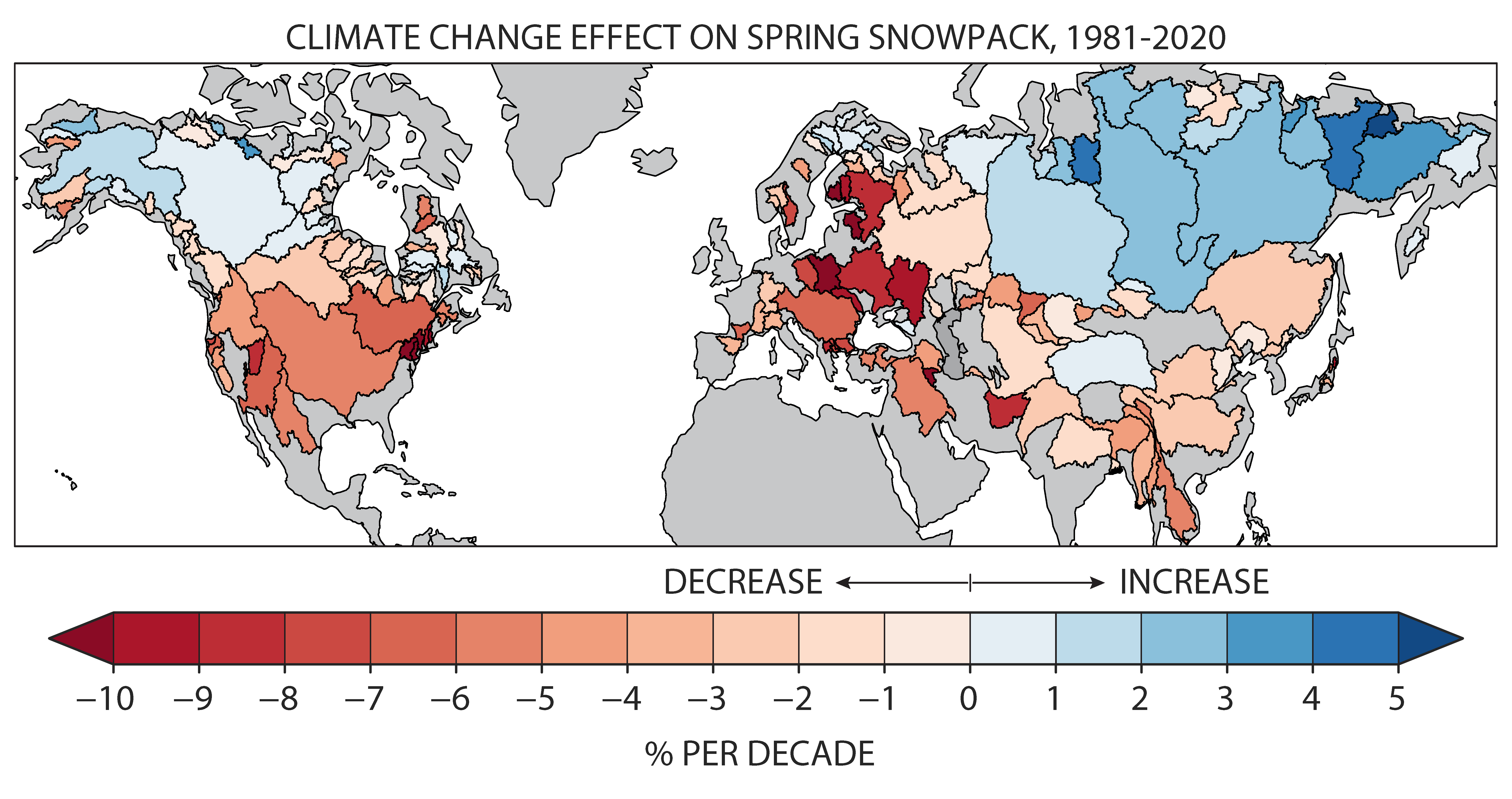

Now, it is “virtually certain” that human-driven climate change is leading to significant snowpack loss in the northeast and southwest United States, a peer-reviewed study from Alexander Gottlieb and Justin Mankin reveals.

Mr Gottlieb told The Independent they achieved this by analyzing several datasets on snowpack melt that all came with degrees of uncertainty and identifying where the datasets all agreed.

“If everything is pointing in the same direction, if no matter which data set we look at we’re getting a clear signal of anthropogenic climate change on snowbank trends, then we can be increasingly confident that what we’re identifying is a true signal and not just an artefact of any individual data set,” Mr Gottlieb said.

Their study also sounds the alarm on a potentially catastrophic problem: the devastating impact of decreased snowpack across the country.

Where is snowpack loss at its worst?

A warming climate disproportionately impacts snow in the northeast and southwest US because the average winter temperatures in these regions are just warm enough that even slight variability can cause noticeable snowmelt.

“As you get to these warmer temperatures closer to the freezing point, your snow becomes incredibly sensitive to even small changes in temperature,” Mr Gottlieb said. “A lot of the river basins in the southwest and northeast US sit in this temperature space, where their average winter temperatures make them incredibly sensitive.”

Because these areas have already proven sensitive to the temperature rise so far, Mr Gottlieb said he expects snow loss to only accelerate as the Earth continues to warm.

Why does snowpack loss matter?

Decreasing snowpacks means less melting snow will run off into the water supply, creating dire consequences in areas where snowmelt is a key component of water infrastructure.

In the southwest, where snowpack melt is among the highest in the US, snowmelt is essential to water infrastructure.

“[Melted snow] is the bridge between the supply of precipitation in the wintertime and people’s demand for that water which really ramps up during the warmer months,” he said.

California’s water system is particularly reliant on snowmelt to serve as a major water source for the state. However, as the climate continues to warm and snowpacks continue to shrink, the state may be faced with a water crisis.

“The train has left the station for regions such as the Southwestern and Northeastern United States,” Mr Gottlieb said. “By the end of the 21st century, we expect these places to be close to snow-free by the end of March. We’re on that path and not particularly well adapted when it comes to water scarcity.”

While the northeast’s water infrastructure is less dependent on snowmelt because the region sees consistent precipitation, this trend could have consequences on local industries, like skiing and forestry, that rely on consistent snow and sub-freezing temperatures.

“There are entire economies that are sort of built around this expectation of having a stable snowpack but are going to be very disrupted by these continued declines,” Mr Gottlieb said.

The skiing economy has already taken a hit from human-driven climate change, even beyond the US.

The study also indicated significant snowpack loss in central and eastern Europe — a trend that hasn’t gone unnoticed among winter-reliant industries. Last year, dozens of ski runs and entire resorts across Europe were forced to close because of record-high January temperatures, The Independent previously reported.

What do we do?

One of the first steps, Mr Gottlieb said, is for scientists and policymakers to document and understand the tangible consequences of the human-driven climate crisis.

“I think we systematically underestimate the actual costs of climate change — not just from a snow perspective, but writ large,” Mr Gottlieb said.

With 2023 being the hottest year on global record “by a large margin,” acting to mitigate the human-driven climate crisis will save not only California’s water systems and Europe’s ski resorts but also put an end to the cascade of extreme weather events bringing severe — even lethal — consequences to millions around the world.

That’s why continued discussion of this topic — and human-driven climate change at large — is essential to mitigating these consequences, Mr Gottlieb said.

“Documenting the impacts of particular changes that we see — whether that’s snow or something else — and really trying to quantify what those impacts are and what their costs to us are, is crucial because I think it highlights just how steep the costs of inaction on climate change are,” Mr Gottlieb said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments