Climate change comes for European skiing: After deadly conditions and closed runs, is this the beginning of the end?

Spring-like temperatures and rain smudged out snowy playgrounds across the Alps from Innsbruck, Austria to Chamonix in France, writes senior climate correspondent Louise Boyle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Europe rang in the year 2023, a blanket of heat silently draped itself over much of the continent.

At least eight countries experienced their highest-ever January temperatures on New Year’s Day. Polish capital Warsaw saw 18.9 degrees Celsius (66 degrees Fahrenheit) -- breaking the previous record by more than 5C. In the town of Delemont, Switzerland, the daily average hit 18.1C (nearly 65F) on 1st January -- more than 2C above the previous record.

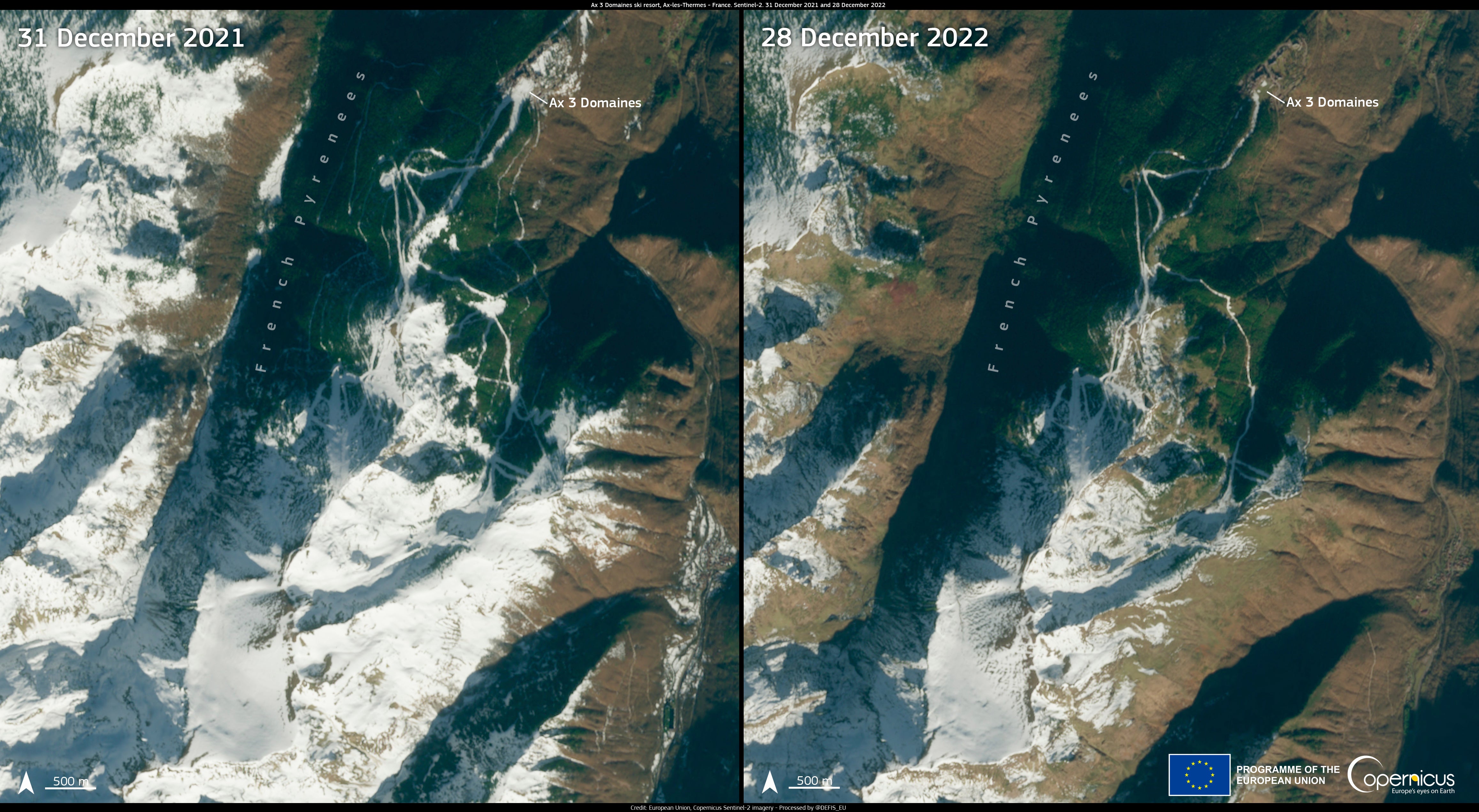

Spring-like temperatures and rain smudged out snowy playgrounds across the Alps from Innsbruck, Austria to Chamonix in France and left behind grassy hillsides dotted with rocks.

Dozens of ski runs closed after snow melted, and some resorts were shuttered entirely in France, Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Bosnia just weeks after a promising start to the season. At the Ski World Cup in Zagreb, Croatia, a race was canceled on Thursday due to high temperatures and strong winds.

“The basic message is pretty simple - humans are warming the planet by burning fossil fuels and we’re seeing these increasingly strong heatwaves in summer but also very warm periods in winter,” Dr Reto Knutti, a climate scientist at research university ETH Zurich, told The Independent.

Last year was the hottest on record in both Switzerland and France and globally, the past eight years are tracking to be the warmest ever. The UK’s annual average temperature was more than 10C for the first time last year, the Met Office confirmed this week, announcing 2022 as the country’s hottest year on record.

Superimposed onto the long-term global heating trend came a persistent flow of warm air from the west and southwest over new year which locked in higher temperatures across Europe.

Dr Knutti grew up in Gstaad in the Swiss Alps, one of the popular ski resorts which started 2023 with very little snow.

“I still go about every winter for skiing,” he said. “I have friends and relatives there, so I’m still very much connected. And that’s where this gets personal because it’s the very same spots where [I] learned to ski. Before anyone was talking about artificial snow, it was just normal that there was snow all the time in winter. And now it’s no longer the case.”

When he recently returned to Gstaad with his children, they went hiking and had a barbecue instead of skiing. ”You can now go to 2,000 meters above sea level and put sausages on a fire,” he said.

Not all European ski resorts were equally affected by the heatwave. At high-elevation Alpine resorts - roughly 2,000 metres above sea level - the snow was relatively normal for this time of year. But lower down, the incredible warmth all but dissolved the snowpack in parts of the northern Alps and across the Pyrenees.

“This is what the climate models have been projecting,” Dr Vikki Thompson, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol, told The Independent. “There will be more hotter spells not just in summer but in winter, too. It will continue to the end of the century - even with big reductions in carbon dioxide output into the atmosphere.”

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading authority on the issue, says the strong declines in glaciers, permafrost, snow cover extent, and snow seasonal duration at high latitudes/altitudes will continue in a warming world.

The scientific assertions will bring little comfort to those with livelihoods bound up in ski seasons and winter resorts. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development warned 15 years ago that rising temperatures could jeopardize as many as two-thirds of European ski locations, and The Times reported this week that some resort operators were holding “crisis talks” about the future.

Iain Martin, a lifelong skier and host of The Ski Podcast, pointed out that there was still plenty of skiing this week at resorts higher up in the mountains.

“But anything below 1,700-1,800 metres, it’s not looking too good as far as this winter is concerned, even with the snow that’s coming next week,” he told The Independent.

He also pushed back against the “climate denial” argument that recent conditions were just typical of a “bad start” to a season.

“In [previous] bad starts, there hasn’t been any snowfall but temperatures have been low,” he said. “This year, there’s been warm temperatures and rain up to quite a high level on the mountain [which] destroys snow.

He added: “Overall the snow coverage is worse, there’s no doubt. If you talk to people on the ground who run businesses, who are able to take a more objective view, then it’s the worst it’s been at this time of year for 20 years, for sure.”

Temperatures will finally drop across Europe this weekend and snow is expected for most of the Alps from Saturday. But that brings another set of challenges.

“If you get a lot of new snow on top of a wet base, then slab avalanches can be more common,” Mr Martin said. “I guarantee that come Sunday, Monday when a lot of snow is due to come down, resorts will have the avalanche scale at the maximum five.”

There have been concerns about safety conditions on some slopes with the Tyrol Hospital Association in Austria telling German newspaper Bild that they have seen a higher number of serious injuries than normal this early in the season. In some Swiss resorts, skiing accidents combined with Covid and flu cases were straining emergency rooms, local media reported.

Austrian authorities have launched a criminal investigation over the death of a 28-year-old Dutch woman who fell and slid at full speed through a safety net into a tree on New Year’s Day on the Hintertux glacier close to the Italian border. Satellite images at the time revealed reduced snow cover and a snowline around 1,300ft higher than normal in the Italian Alps. Her friend was also seriously injured, and two others were later hospitalized from separate accidents on the same glacier.

It’s not known if a causal link exists between the recent lack of snow and ski injuries and fatalities in what is already an inherently risky, extreme sport.

However, there were some notable consequences to having less snow. Mr Martin said that the reduced number of slopes, which had enough snow to remain open over the new year period, were busier.

He also pointed out that the lack of snow at lower altitudes could potentially push less experienced skiers further up mountains and onto more difficult pistes in search of powder.

Many snow-starved resorts were plugging the gap with artificial white stuff. In the Swiss resort of Adelboden, which saw temperatures remain above freezing, even at 6,500ft, this weekend’s ski World Cup will be bolstered by artificial snow.

“The climate is a bit changing but what should we do here? Shall we stop with life? Everything is difficult,” course director Toni Hadi told The Guardian.

Notably, manmade snow and real snow are “substantially different”, Dr Dan Cziczo, professor and department head of the Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at Indiana’s Purdue University, previously told The Independent. “I think most people find [artificial snow] to be much icier and slicker,” he said.

Some elite Alpine athletes have previously raised concerns about artificial snow.

“We go very fast on the downhills,” US Olympic gold medalist and Nordic ski team member Jessie Diggins told AP last year, noting she had reached speeds of 76 kilometers per hour (47mph) downhill on manmade snow. “I think it is getting a little more dangerous and I’ve noticed at the World Cup when it is manmade snow, it is scary because instead of sliding on snow you’re sliding on ice. I think we’re seeing a higher percentage of falls. I feel it is a little more dangerous now.”

Artificial snow also comes with an even greater dilemma: Making it is an extremely water-intensive process, taking 200,000 gallons to cover an acre with a foot of snow, by one estimate. This becomes a difficult equation particularly after Europe experienced its worst drought in at least 500 years last summer.

The lack of real snow could also play a role in how severe drought conditions become this summer, Dr Thompson noted. If snow melts earlier in the year, there will not be big increases in water runoff into streams and rivers typically expected in spring.

“The soil moisture levels will be all messed up and could dry out sooner” she said. “Depending on what happens in the springtime, it could have pretty big impacts for the summer drought situation.”

Then there is the carbon footprint. Robin Smith, president of snow gun manufacturing and consulting company MYNEIGE Inc, told ESPN in 2021 that he estimated around 67 per cent of energy consumed at ski resorts each season goes on snowmaking.

It’s also incredibly expensive and can leave resorts with bills for millions of dollars each season.

“At this point, even if we reduce CO2 emissions, we’re predicting that the snowline might go up by another 400 metres,” Dr Knutti said.

While he predicted that resorts at higher altitudes will continue to operate, the decrease in snow suggests that while skiing would still be possible at resorts below 1,500 meters, it would no longer make sense economically.

“Typically people say that you [need] 100 days in a winter to do something economically viable,” he said. “With less, it just doesn’t make sense. The infrastructure is too expensive, and people will no longer come because they fear that there will be no snow. So the low-lying areas, I think they will just have to stop. The problem is it’s hard to abandon these things. For areas where skiing was the way people survived for a century, it’s hard to accept that it doesn’t work anymore so they keep trying. In the end, I think they’re going to have to give up.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments