Radioactive water travelling from Fukushima power plant being measured by scientists

Researchers are attempting to predict the amount of radioactive water from Japan that will hit the North American coast.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The concentration of radioactive water from the Fukushima power plant in Japan expected to hit North American coasts should be known in the next two months.

So far only small traces of pollution have been recorded in Canadian continental waters, but this is expected to increase as contaminants move eastwards on Pacific currents, BBC News has reported.

In 2011, three nuclear reactors at the Japanese facility went into meltdown, leaking radiation into the Pacific Ocean.

Researchers from the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Canada have been analysing water along a line running almost 2,000km due west of Vancouver, British Columbia, since the 2011 Fukushima accident.

In June 2013, radioactive caesium-137 and 134 were detected in the entire line of the sampling length.

Scientists stress that even with the probable increases taken into account, the measurements will be well within limits set by safety authorities.

Researchers have harnessed the radioactive water to test two forecasting models to try and map the probable future progression of the plume of radioactive water.

Using one model, the scientists have predicted that a maximum concentration of 27 becquerels per cubic metre of water will appear on the Canadian coast by mid-2015, but the other model predicts no more than about two becquerels per cubic metre of water.

Bedford’s Dr John Smith told BBC News that further measurements currently being taken in the ocean should give researchers a fair idea of which model is correct.

Speaking to reporters at the Ocean Sciences Meeting 2014 in Honolulu, Hawaii, he also stressed: “These levels are still well below maximum permissible concentrations in drinking water in Canada for caesium-137 of 10,000 becquerels per cubic metre of water – so, it’s clearly not an environmental or human-health radiological threat.”

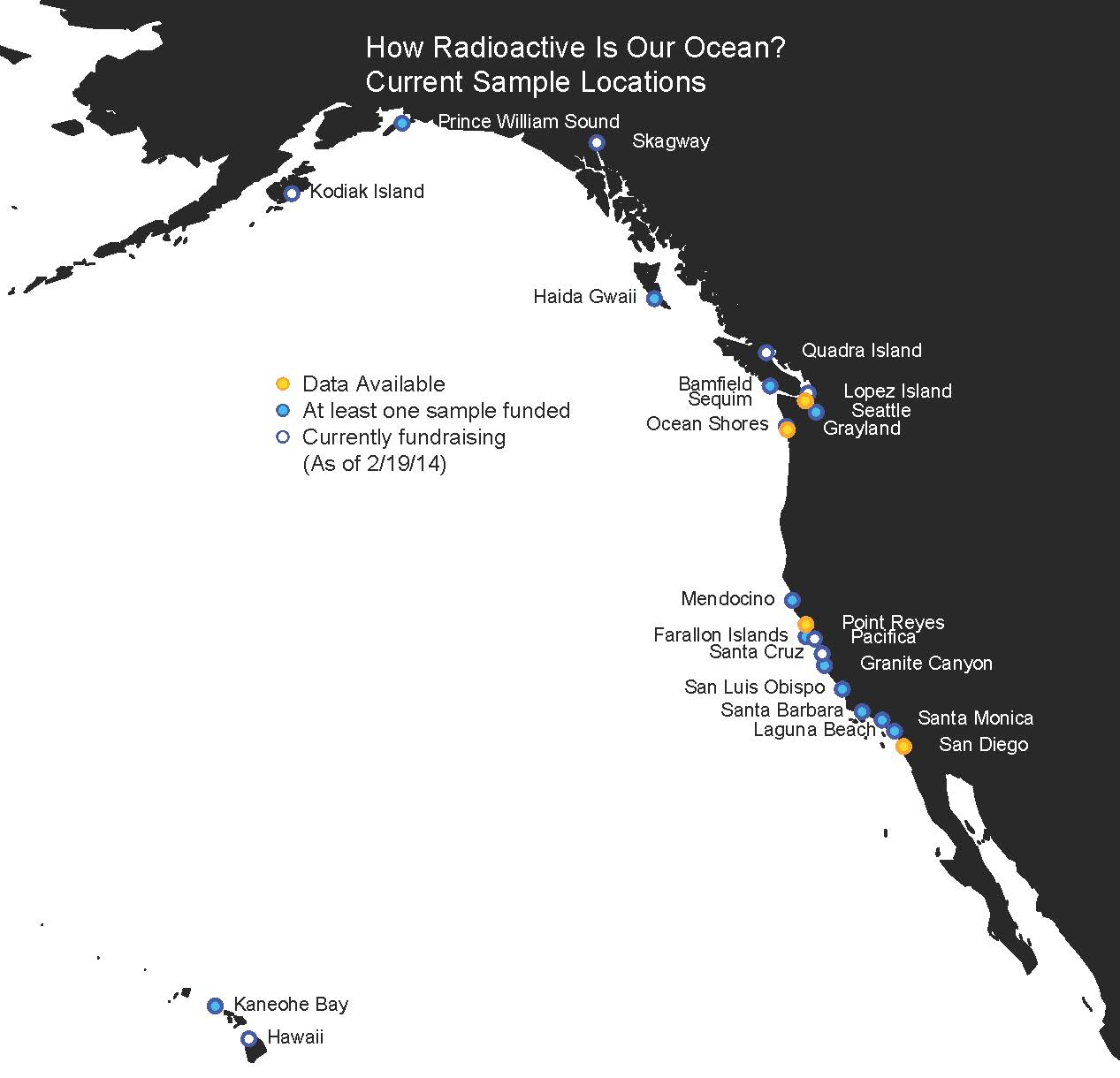

Dr Ken Buesseler from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), who was also speaking on a Fukushima panel at the event, described how citizens are involved in the effort to record radioactivity in beach waters on the western United States.

Members of the public are being recruited to regularly gather water samples from California to Washington State and in Alaska and Hawaii.

Caesium-134 has not yet been detected in these areas, but Caesium-137, which was also released by the damaged power plant, is already present in the water after A-bomb tests in the 1950s and 1960s.

However, Dr Buesseler expects a specific Fukushima signal from both radionuclides to be evident very shortly in US waters.

The ourradioactiveocean.org sampling project, which is organised at the website, is being funded through private donation because no federal agency has picked up the monitoring responsibility.

“What we have to go by right now are models, and as John Smith showed these predict numbers as high as 30 of these becquerels per cubic metre of water,” he told the BBC.

“It’s interesting: if this was of greater health concern, we’d be very worried about these factors of ten differences in the models.

“To my mind, this is not really acceptable," he said.

Mr Smith added: "We need better studies and resources to do a better job, because there are many reactors on coasts and rivers and if we can’t predict within a factor of 10 what caesium or some other isotope is downstream - I think that’s a pretty poor job.“

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments