Poorest households hit hardest by UK climate change levy despite using least energy

Those on low incomes get less back from home-improvement schemes than they pay in government charges

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The UK is one of the leading countries in addressing climate change. As well as signing international agreements, the country has its own target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent from 1990 levels by 2050. And as part of the effort to meet that target, the government has added a levy to business and household energy bills. The average household energy bill is around £1,030 a year and the charges effectively act as a levy that costs households an average of £132 (2016 figures).

The good news is that the levy is working. About 20 per cent of the levy is spent on improving the efficiency of homes. This is done by funding schemes such as the Energy Company Obligation, which provides insulation and other energy-saving measures to low-income households. The average household energy bill would be £490 higher without these improvements. The money is also spent on research to improve renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, and help bring down their cost.

But is this really a fair way to raise the money? Our new research shows that the poorest households not only are hit hardest by the levy but also receive less money back in the form of home improvements than they contribute in the first place.

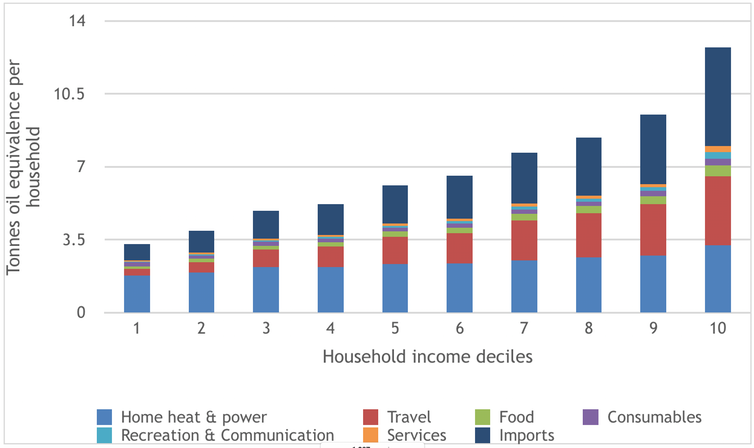

To study the levy, we divided the UK into “income deciles”, 10 groups each representing 10 per cent of the population, divided from the lowest to the highest income. We then looked at how much energy use they were responsible for, both directly through their electricity, gas and fuel use, and from the other goods, services and infrastructure they use. The levy is only raised on a limited number of these “energy service demands”, namely home heat and power. So if your overall energy demand is higher for heat and power and lower for other services, you’ll pay a proportionally higher amount of the energy policy costs.

We found that, in a year, the richest households each consumed on average the same amount of energy that would be produced by 12.7 tonnes of oil, compared to 3.3 tonnes for the poorest households. But the poorest spent a much greater proportion of their income (10 per cent) on energy than the richest (3 per cent). And the energy used for heating and powering their homes – the part that their climate-change levy bill is measured on – represented a much greater proportion of their overall energy use.

This means that adding the climate-change levy to household energy bills hits the poorest households hardest. Energy bills account for a much greater share of their household income and more of their energy use is charged. In fact, the levy only affects a quarter of the total energy consumption of the richest households, compared to 53 per cent for the poorest households. As a result, the richest homes use nearly four times more total energy than the poorest but only pay 1.8 times more towards energy policy costs.

One argument for the climate-change levy is that poorer households benefit more because part of it is used to improve the efficiency of their homes. But we estimate that the poorest 10 per cent of households currently pay £271m a year towards the levy, while the costs of the Carbon Savings Communities and Affordable Warmth schemes, which are designed to help the poorest homes, come to just £220m a year.

Fairer alternatives

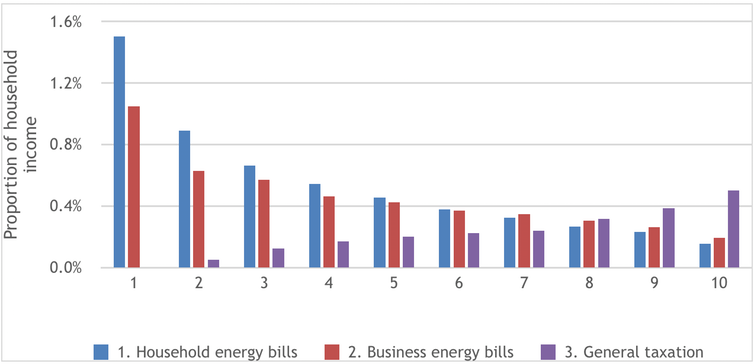

We also compared the system of adding a levy to household bills to two other ways of funding energy policy. The first was adding a levy to the energy bills of businesses (including energy suppliers), at least some of which would be passed on to households who buy their goods and services. The second was paying for the policy with money raised from income tax.

We found that the household levy is the most regressive system. Costs are placed purely on household bills, with the richest households paying 0.16 per cent of their income compared to the poorest paying 1.5 per cent (over nine times more).

Adding a levy to business bills is an improvement. Under this system, the richest homes pay 0.19 per cent of their household income and the poorest pay 1.05 per cent (still nearly six times more).

But funding energy policy from income tax would mean that the lowest income households wouldn’t contribute at all and the richest households would pay 0.5 per cent of their income. Compared to a household levy, this approach would reduce costs for 70 per cent of UK households, while the richest 30 per cent would see an increase. The lowest income group would save £102 a year, at an additional cost of £410 for the richest households – which, at less than £8 a week, would make a relatively small difference to their lives.

Our analysis shows that the more you earn, the greater your energy demand, yet this is not reflected in current energy levy policy. It’s important to make sure that the costs associated with low-carbon transitions are met by the households that cause the problem and those who can afford it, instead of hurting poorer households. We see it as essential that climate policies are compatible with social justice. Our research demonstrates it is clearly possible to design a system that is both fair and effective.

John Barrett is a professor of energy and climate policy, and Anne Owen is a research fellow in sustainable consumption, at the University of Leeds. This article was first published in The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments