Scientists confirm climate change played a role in Pakistan floods by increasing rainfall

Research by World Weather Attribution shows climate crisis played role by intensifying rainfall in region by 50-75 per cent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A scientific study has found that the climate crisis did have a role in Pakistan’s historic floods this year which caused an unprecedented scale of devastation in the country, killing 1,400 people and impacting over 33 million people.

The excessive rainfall and flooding this year was widely dubbed as a climate catastrophe with UN chief Antonio Guterres describing the devastation as “climate carnage” and Pakistan’s government holding rich countries responsible for the havoc.

However, this is the first time a scientific study has been carried out to assess the role the warming planet has played in the occurrence and intensity of these floods.

The research released by World Weather Attribution (WWA), an initiative for conducting real-time attribution analysis of extreme weather events, shows the climate crisis has indeed played a role in Pakistan’s floods by intensifying the rainfall in the region by 50-75 per cent.

The rapid attribution study, conducted by 26 researchers from 10 countries, used scientific models and historic data to determine how likely such an extreme event would have been if the world had not already warmed by about 1.2C since the late 1800s, and how frequent the event would become as the planet continues to warm.

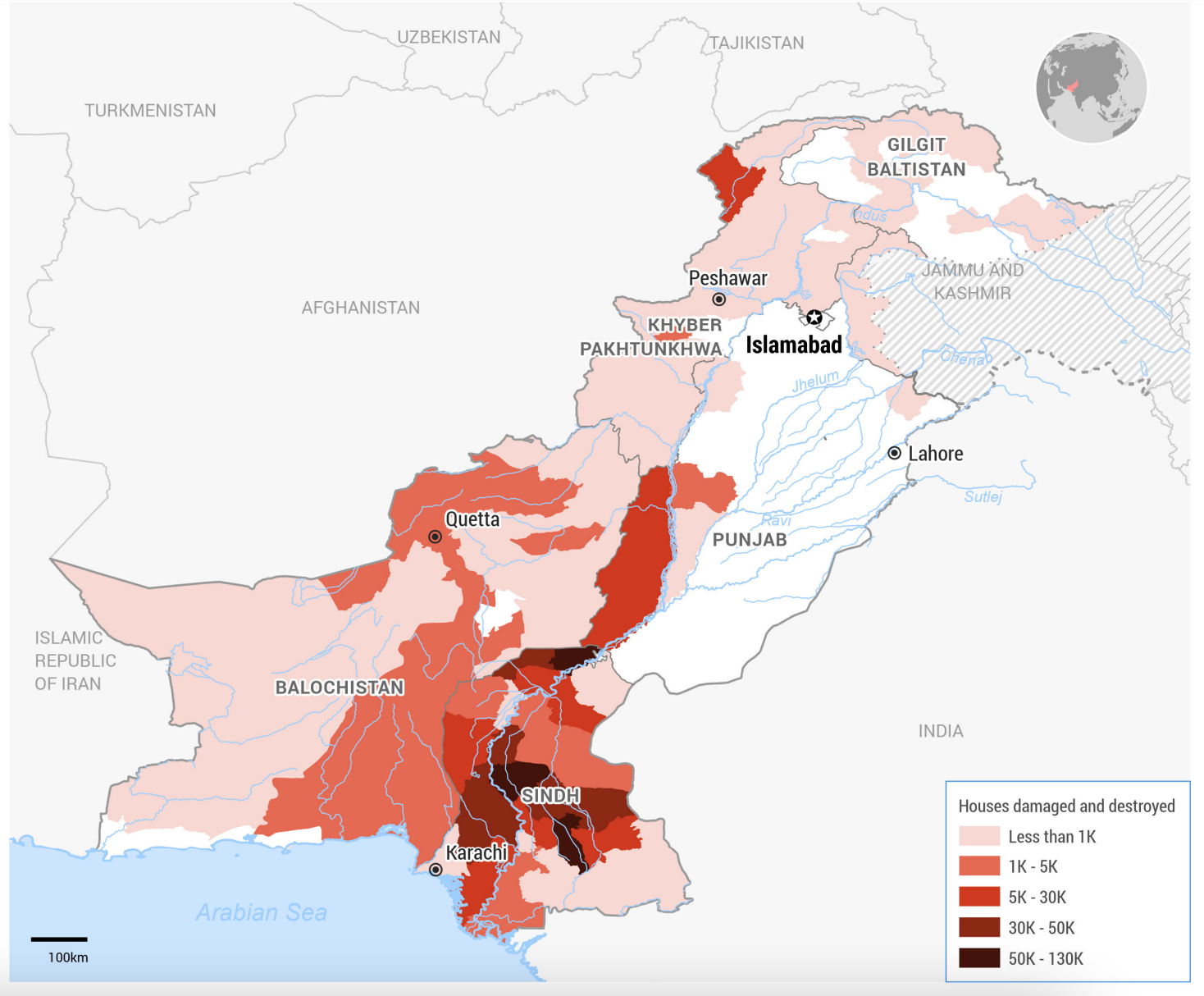

Two datasets were used in the study – first was the 60-day period of heaviest rainfall over the areas surrounding the Indus river, the largest river in Pakistan, in June and September. The second was the five-day period of the heaviest rainfall in the southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan, which suffered heavy flooding.

Researchers used published, peer-reviewed methods and found that climate change increased the intensity of rainfall in the five-day period in Sindh and Balochistan by up to 75 per cent. While the 60-day monsoon period was around 50 per cent more intense due to warming.

The southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan have been heavily hit by the flooding in the last few weeks and have witnessed their wettest August ever recorded. Terms such as “monster monsoon” and “monsoon on steroids” have been used by officials to describe the unusual rainfall the region has witnessed.

The two states received seven and eight times their usual monthly total rainfall respectively this season. Pakistan as a whole has received more than three times its usual rainfall in August.

The study found that such phenomena can occur once every 100 years, or in other words, has a 1 per cent chance of occurring every year, due to the current levels of warming.

“The same event would probably have been much less likely in a world without human-induced greenhouse gas emissions, meaning climate change likely made the extreme rainfall more probable,” it said.

However, as the world is set to warm further from the current 1.2C warming despite efforts to limit it by 1.5C as enshrined in the international Paris agreement, such events are feared to become much more likely to occur. The situation could be even worse with a 2C warming.

Also read: InFact: What would be the difference between 1.5C and 2C global warming?

As a limitation, the WWA noted that there were some uncertainties in assessing the impact on the overall monsoon period due to a lack of data and high variability in rainfall in the region.

“Our evidence suggests that climate change played an important role in the event, although our analysis doesn’t allow us to quantify how big the role was,” said Dr Friederike Otto, co-lead of WWA and senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute.

Dr Otto said the “mathematical uncertainty” is because the region has very different weather from one year to another, which makes it hard to see long-term changes in observed data and climate models.

However, she added the findings are in line with what climate projections have been predicting for years.

“It’s also in line with historical records showing that heavy rainfall has dramatically increased in the region since humans started emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. And our own analysis also shows clearly that further warming will make these heavy rainfall episodes even more intense.”

She added: “While it is hard to put a precise figure to the contribution of climate change, the fingerprints of global warming are evident.”

The intensity of rainfall in the region is driven by several weather patterns, such as the La Niña event and the arrival of multiple depressions from the Bay of Bengal, something that makes Pakistan highly prone to heavy rainfall.

However, the climate crisis is known to have also contributed to the changes in variability of the weather systems like eastern monsoon rains and western disturbances in the region, something meteorologists have been pointing at for quite some time.

The WWA study also found links between the historic rainfall with the worsening heatwave, which the initiative had earlier found to have become 30 times more likely in a research published in June this year. Scientists and climate activists have been pointing at this connection for quite some time as hotter air traps more moisture.

It also mentioned the role of melting glaciers in swelling up the rivers, something that was exacerbated due to the deadly heatwave in April-May when parts of Pakistan saw temperatures soaring up to 50C. Pakistan is home to over 7,000 glaciers, the highest for any country outside the poles.

The findings of the study are in line with the IPCC sixth assessment report which projected more intense rains in South Asia as the planet warms, a region considered one of the most vulnerable to the worsening impacts of the climate crisis.

The research concludes that the scale of the devastation also had multiple factors behind it. Pakistan’s infrastructural vulnerabilities, high population density, poverty rates and political instability played a huge role in the extent of damage it suffered.

Pakistan government’s preliminary assessment says the country suffered around $30bn worth of damages, something it will take years to overcome. Meanwhile, millions of people have either been displaced or have gone through significant losses.

The country is also staring at a public health crisis as water-borne diseases spread among vulnerable people, something aid agencies say can be a bigger disaster than the floods. The flooding has also increased calls for more climate finance and compensation from rich countries.

Not just in Pakistan, but in light of frequent extreme weather events around the world, the calls for loss and damage fund are picking momentum. Loss and damage is a term used in climate negotiations to refer to the money rich countries owe to vulnerable nations suffering the impact of the climate crisis.

“Fingerprints of climate change in exacerbating the heatwave earlier this year, and now the flooding, provide conclusive evidence of Pakistan’s vulnerability to such extremes,” Fahad Saeed, Researcher at the Center for Climate Change and Sustainable Development, Islamabad, Pakistan said at the release of the study.

“Being the chair of G77, the country must use this evidence in Cop27 to push the world to reduce emissions immediately,” he added. “Pakistan must also ask developed countries to take responsibility and provide adaptation plus loss and damage support to the countries and populations bearing the brunt of climate change.”

However, despite increasing evidence of climate crisis making extreme weather more frequent, the issue remains a contentious point and it is yet to be seen how the upcoming UN climate summit, Cop27, would be able to bring any consensus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments