Chemicals which created hole in Earth’s ozone layer are making a comeback

Researchers speculate alternative refrigerants may be to blame

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chemicals which caused the hole in Earth’s ozone layer are growing at alarming rates despite an international ban, a new study has found.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), man-made gases once widely used in air conditioners and refrigerators, were banned in 2010 in a landmark international agreement called the Montreal Protocol.

Since then, alternative substances were introduced which were believed to be less harmful to the ozone layer.

But alarming new research, published on Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, found that CFCs have continued to increase in the atmosphere, reaching record highs in 2020.

Researchers measured CFCs at 14 locations around the world but remain in the dark about the source of the increase.

Researchers speculated that alternative refrigerants may be to blame for the rise in CFCs.

“Emissions of these few gases are at the same level as the emissions of all greenhouse gases in Switzerland,” Stefan Reimann, a researcher from Empa, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, told a press briefing, according to The Verge.

“Being from Switzerland that’s really something which boggles me.”

The discovery of harmful CFC levels is a significant setback to global efforts to repair the ozone layer.

The ozone layer absorbs most of the harmful UV radiation from the sun, preventing it from reaching Earth’s surface.

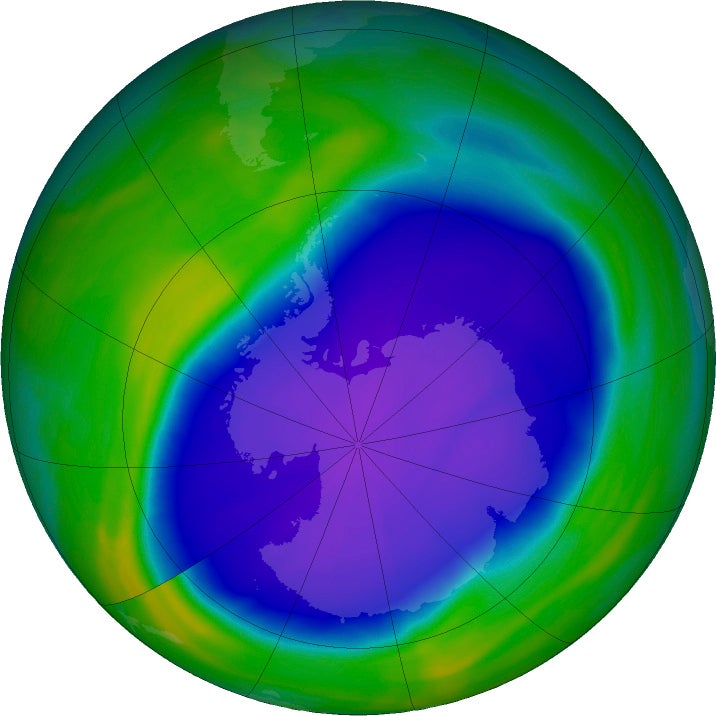

In 1985, scientists discovered a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica which led to increased regulations around the ozone-depleting substances before they were banned in 2010.

Since then, the ozone layer has been on the mend, reducing the risk of skin cancer and cataracts. Scientists expected that the ozone layer would resemble its pre-hole state by 2066 over Antarctica, and by 2045 over the Arctic.

However, the new study is an unexpected and unwelcome development.

Researchers speculated that a loophole in the Montreal Protocol allowed certain types of CFCs to proliferate, as companies are still permitted to use them in the process of manufacturing alternatives.

Three of the five CFCs that have become prevalent since 2010 are used to produce hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), the replacements for CFCs, in air conditioning and refrigerators.

The new study suggests companies may not be containing leaks and destroying remaining CFCs as intended.

HFCs also pose problems as they are “super” greenhouse gases and much more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of their contribution to the climate crisis.

The use of HFCs is expected to decline by 85 per cent by 2047, thanks to the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

The pollution from the five types of CFCs studied, however, remains relatively low and may not be enough to undo progress in repairing the ozone layer. But scientists fear that the rise in emissions could counteract progress in tackling climate change.

Action towards saving the ozone layer under the Montreal Protocol is estimated to have prevented global heating by an estimated 0.5C.

Researchers said more stringent monitoring and enforcement of the Montreal Protocol is needed.

“Eradicating these emissions is an easy win,” Luke Western, a research fellow at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Bristol, at the press briefing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments