From silenced birdsong to starving manatees: What we lost from the natural world in 2021

From Kenya to the Florida Keys, nature is in crisis due to impacts linked to the rising global temperature, Gino Spocchia writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are amid a global biodiversity crisis. Humanity’s impact on the planet is now so overwhelming that 1m plant and animal species are at risk of extinction, the UN recently reported.

Nature is suffering the world over, from Kenya to the Florida Keys, due to impacts linked to the rising global temperature.

Below are just a sliver of the losses to the natural world in 2021, and a sombre reminder of what is at stake.

Silent Spring: Birdsong is dying away

Bird populations around the world have declined most rapidly where warming is most pronounced, research has found – and in the process, birdsong has fallen silent.

A team of researchers associated with the University of East Anglia (UEA) sounded the alarm in November, following an attempt at analysing historical birdsong.

The study combined data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey and Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme sites with recordings of more than 1,000 species from Xeno Canto, an online database of bird calls and songs.

Researchers analysed how the soundscapes of Europe and North American had changed in frequency and volume, and found that birdsong was now quieter and less intense across the continents.

Some of the birds that could be heard in the database were warblers, which are migratory birds, as well as wood pigeons, black birds, and blue tits – which can be seen in the UK all-year round.

The researchers linked this phenomenon to increased global heating, which has seen migratory birds in particular change their movements to and from breeding sites, according to a study in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

“Given that people predominantly hear, rather than see, birds, reductions in the quality of natural soundscapes are likely to be the mechanism through which the impact of ongoing population declines is most keenly felt by the general public,” said Dr Simon Butler, lead author of the UEA study.

Parallels were drawn between the increasingly silent natural world and the seminal 1962 book, Silent Spring, by American biologist and conservationist, Rachel Carlson, which warned of human effects on the environment, particularly of pesticides.

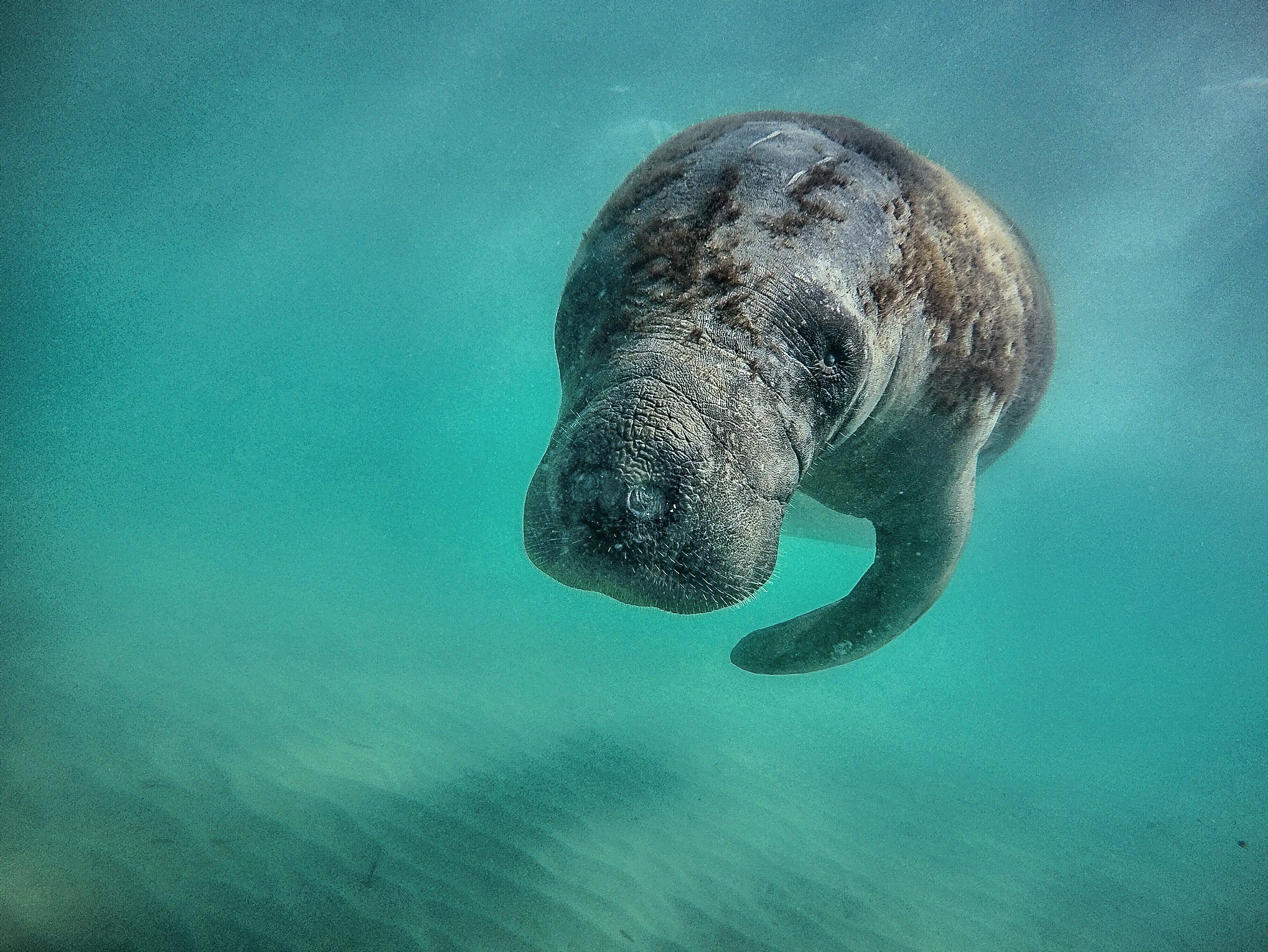

Manatees on the brink

Manatee populations in Florida are in worrying decline. Official figures in November revealed that more than 1,000 of the slow-moving creatures have died in 2021, breaking a previous annual record.

Authorities and wildlife campaigners cited warming ocean waters, combined with pollution and algal blooms that are destroying seagrass beds which manatees feed off.

The situation is so dire that Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Service has for the first time established a limited feeding project in Cape Canaveral along the Indian River Lagoon where manatees congregate in winter months, in an attempt to stop more manatees dying.

Patrick Rose, director of Save The Manatee Club, said: “Saving manatees is part of saving the ecosystem. If we can get this taken care of manatees will flourish. If we don’t, they won’t”.

An advocacy group, Defenders of Wildlife, put it more forcefully: “Manatees are starving to death.”

North Atlantic right whales: Shrinking on all fronts

The population of North Atlantic right whales has fallen further after the International Union for the Conservation of Nature reclassified them as critically endangered in July 2020.

A report, published in the journal Oceanography in September, cited warmer waters in the Gulf of Maine, which is killing off fatty crustaceans which the whales feed on. As few as 356 of the whales are thought to be in existence.

“When they can’t build those thick layers of blubber, they’re not able to successfully get pregnant, carry the pregnancy and nurse the calf,” said Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, a marine ecologist at the University of South Carolina and a study author.

A second study, published in Current Biology in June, found that North Atlantic right whales are becoming smaller as a consequence of several factors that have stunted growth.

Researchers cited fishing net entanglements, ship collisions, along with changes to food available for the whales as a result of warming ocean temperatures.

Newborns are now around 1 metre – or 7 per cent – shorter than a whale born in 1980, the study’s lead author, Dr Joshua Stewart, of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said.

“A whale entangled for a year in fishing gear is expected to reach a maximum length about 60cm shorter than one who is not. On top of that, we found a whale born today is expected to reach a maximum length about a metre shorter than a whale born in 1980.”

Northern white rhinos – without alternatives

Only two northern white rhinos are left on the planet – and this year it was announced that just one is capable of breeding, and saving the species.

Keepers at a wildlife sanctuary in Kenya announced in October that Najin, a northern white rhino, would be retired from an ambitious breeding initiative after the “weighing up risks and opportunities for the individuals and the entire species”.

It means that only one northern white rhino, Najin’s daughter Fatu, is left to procreate. Mother and daughter live at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya under high security.

Since the death of the last male northern white rhino in 2019, breeders have experimented with a technique allowing female rhinos to be artificially inseminated.

While two embryos have been created in a laboratory using the eggs harvested from Najin and Fatu, the initiative has yet to implant them into a surrogate mother – most likely a southern white rhino.

Habitat loss, driven by illegal logging and agriculture, have been blamed for almost killing off the northern white rhino.

Rhinos in Asia and India, where the species numbers are higher, are meanwhile threatened by habitat degradation as a result of warming temperatures, as well as human activity.

Polar bear populations on ice

A study published in September suggested that polar bears have begun to inbreed to survive, as the Arctic’s most iconic animal adapts to rapidly-melting sea ice destroying its natural hunting grounds.

Between 1995 and 2015, polar bears roaming Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago lost as much as 10 per cent of the population’s genetic diversity because of the impact of global heating, researchers said.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, polar regions are melting almost 13 per cent per decade, and over the past 30 years, the oldest and thickest ice in the Arctic has dropped by a shocking 95 per cent. That has shrunk territories that polar bears roam.

Simo Maduna, of the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research and study author, toldABC News , that with inbreeding “comes risk in the sense that some of the traits that are recessive, [and] will now basically be unmasked in the population”.

That could reveal abnormalities in polar bears born in future, and risk the predator’s ability to survive.

Last gasp: Giraffes killed looking for water

The sorry sight of six dead giraffes that were pictured in Kenya’s Garissa County in December showed the animals stuck in mud, where they were trying to reach a water source.

Kenyan wildlife authorities said the giraffes were found to have been weak from starvation before getting stuck in the mud inside the Sabuli Wildlife Conservancy in Wajir, almost 280 miles north east of Nairobi.

Photojournalist Ed Ram, who captured the image, said the giraffes were too weak to pull themselves free.

“When you approach many of the villages in the region, there’s dead cows that line kind of sand tracks as you get to the villages, in various states of decomposition,” he told CBC News. “And the cows that were remaining were very emaciated.”

Kenya has been battling an intense drought driven by the climate crisis, with the country’s president declaring a national disaster in September as this year’s rainy season followed recent patterns of very little rainfall.

Some 4,000 giraffes in Kenya are under threat, according to local newspaperThe Star , as the extreme drought conditions continue to threaten their food and water resources.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments