String bags are not the only 1980s relic that could help fight climate change

Who remembers cardboard boxes at the end of supermarket tills? Glass milk bottles? How about the bottle deposit scheme? We don’t need the tech of the future to make eco-friendly choices at home, says David Barnett. We can find everything we need in our not-so-distant past

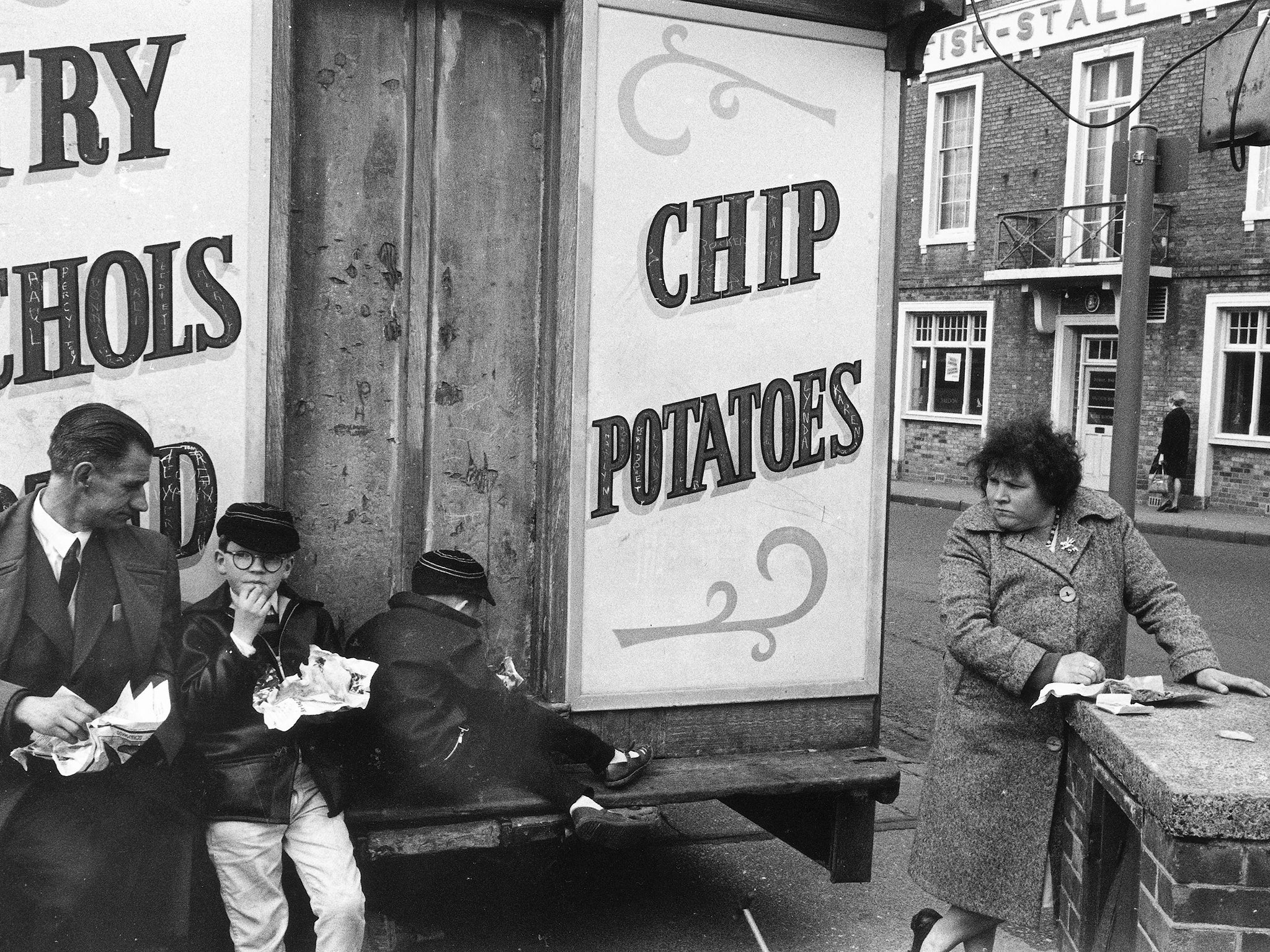

When I was a kid at the turn of the 1980s, one of my most hated jobs was being sent to the fish and chip shop. Not, you understand, because I didn’t like fish and chips; rather because I would invariably be sent with a clanking nest of bowls and a tea towel. It was all right if anyone wanted just fish and chips, or pie and chips, because they were wrapped in newspaper – indeed, today’s news was tomorrow’s chip wrapping. But if there was any moistness attached to the order – gravy, or the Wigan delicacy of “pea-wet” (the juice from the simmering peas) – then a receptacle was required.

I think polystyrene trays had probably been introduced by then, and I would often bemoan the fact I had to hand our own dishes over the counter to be gently warmed before the food was put in them, wrapped in paper and then covered with our tea-towel for extra insulation. But my mother would never countenance a plastic tray… not, I don’t think, through any desire to save the planet, but because they cost an extra couple of pence.

I was given pause to think of this when hearing that Morrisons was introducing string bags for shoppers. Or should that be reintroducing? When I was young, no self-respecting nan would be seen out at the shops without a string bag. And for a bigger shop, produce would be placed directly into a wheeled shopping trolley.

Bags provided by the shops were just not a thing, especially plastic bags. If you went to the supermarket, there were often piles of cardboard boxes at the back, near the tills, which you would use to load up your goods and take them to the car (or bus stop).

Morrisons says that the £1 reusable, washable string bags – made from unbleached and untreated recycled cotton – are designed so that fruit and veg and other loose produce can be carried home “just like shoppers from the 1970s and ’80s”.

Natasha Cook, packaging manager at Morrisons, says: “As we increase the number of loose fruit and veg we stock, we’ve listened to customers – who said they wanted plastic-free bags to carry it home in. In our trials, customers said they felt a sense of nostalgia using the string bag – as it reminded them of shopping trips of the past.”

Which is a salient point, because as the world wakes up to the fact that we have to make some changes pretty quickly to combat the effects of climate change and pollution, many small solutions might well be in our fairly recent history.

It isn’t very long ago that just six short minutes of footage in the final episode of David Attenborough’s BBC wildlife documentary series Blue Planet II galvanised many people into taking action against the single-use plastics that are clogging up our seas and having a devastating effect on the natural world.

Plastic bags are seen as one of the worst offenders, with a five pence charge brought in designed to reduce consumption and steer shoppers towards reusable “bags for life”.

These days most of us are a lot more savvy about recycling. The latest figures from the government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs says that household recycling is 45.7 per cent of total waste, compared to 45.2 per cent a year earlier.

There is an EU target for the UK to recycle at least 50 per cent of its household waste by 2020, though what that will mean post-Brexit is uncertain.

But the percentages don’t tell a story as starkly as the actual figures. In 2016, the UK generated 222.9 million tons of waste, with England responsible for 85 per cent of that figure.

We are throwing a lot of stuff away, in other words. But it wasn’t always the case. Just 30 or 40 years ago, there was far more emphasis on reusing and repairing. Indeed, it was easier to replace something than fix it. I remember at one point in the 1990s throwing a perfectly good printer in the bin. Why? Because it was cheaper to buy a new one than purchase some new ink.

My mother would have been appalled because she was part of the “make do and mend” generation. When I was a child, new clothes were for Easter, Christmas or birthdays. The rest of the time they were patched up and had to put in more service until they could stagger on no more. School trousers were bought long, and hemmed up; the hem slowly dropped over the course of a year as you grew. People learned to fix and maintain things. I can remember my dad looking blankly at me when I had my first car, aged 18, and told him that I’d taken it to the garage to get it serviced. He couldn’t conceive of paying someone to do that when you could do it yourself.

What goes around comes around. Last April the Levenshulme Repair Cafe opened up in a church community centre in the town to the southeast of Manchester, just for two hours on Saturday mornings. It was the second repair cafe to open in Manchester, the first one being in Chorlton; now there are five.

If you’ve seen Channel 4’s Repair Shop show you’ll know the score: people take things in and a team of experts try to make them as good as new. But while the TV show focuses on antiques and heirlooms, the Levenshulme Repair Cafe takes a more practical, pragmatic approach.

Jack Laycock is part of the Repair Cafe team and says there is a pool of about 10 volunteers with repair skills in a variety of areas – bikes, sewing, electrical goods, computers, furniture. Not everyone is available every week, and Laycock puts up on the cafe’s Twitter feed (@LevRepairCafe) what kind of expertise will be on hand on each given Saturday.

The public turns up with their broken things to see if they can be repaired. “We have a success rate of about 70-80 per cent,” says Laycock. “And if we can’t fix it, the experts will offer advice on what to do next, or how to best replace it.”

A wide range of people attend the sessions – not just the older generation, but lots of younger people and families with children. They bring in everything from items of clothing that need stitching to washing machines.

Laycock says: “I think more people come to get something fixed through environmental concerns rather than saving money. They’re very aware of how much rubbish is thrown into landfills and people are wanting to try to repair things a lot more now.”

Which isn’t always easy. Many items have obsolescence designed into them – Laycock says the volunteers have to be extremely resourceful and create their own tools to deal with unique fixings and closings. He says: “Some items, especially electrical ones, are made so you can’t get into them, or they have screws with very unusual heads that are fitted really deeply into the casings.”

It’s almost as if the manufacturers don’t want you to fix the things you buy, preferring you to throw it in the skip when it goes wrong and buy a new one. Which is why on 1 October the EU brought in new “right to repair” legislation.

This stops manufacturers making products, especially white goods, which are impossible to repair because the parts aren’t widely available. Campaigners say the legislation doesn’t go far enough, because it only makes provision for professional repairers, not the consumers themselves, to be able to get hold of the necessary parts. But it’s certainly a step in the right direction.

While there are many jobs that the average person wouldn’t dream of tackling, there is a lot that they can do with items such as furniture, bikes, clothing and toys, and the Levenshulme Repair Cafe is all about teaching people those skills as well as fixing their broken stuff.

“It’s like the old adage about give a man a fish and you’ll feed him for a day, but teach him how to fish and you’ll feed him for life,” says Laycock. “When someone brings an item in our experts will sit down with them and show them the problem, and what they’re doing to fix it. They can pick up that skill, and next time they can do it themselves, and show other people how to do it.”

I think more people come to get something fixed through environmental concerns rather than saving money. They’re very aware of how much rubbish is thrown into landfills and people are wanting to try to repair things a lot more now

There’s definitely an appetite for fixing rather than binning. Thanks to the activism of the likes of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion, we’re becoming more aware that the fight against climate change is fought on several fronts: through legislation and action at government level, and via our own, smaller-scale but no less important efforts at home.

Just like people did in the 1970s and 1980s, with their string bags and shopping trolleys, before disposable consumer culture took hold. What else could we learn from those days? How about using a lot more glass?

Mark Hall works at York-based Business Waste and he’s positively evangelical about bottles. He waxes poetic about the days when milk used to be delivered in glass bottles – not plastic cartons – and after using it you’d wash out the bottle, put it on the step, and the milkman would collect and reuse it.

Hands up if you’re old enough to remember the bottle deposit scheme? This was when you bought a bottle of soft drink from a local shop and there would be a few pence extra charge, which was refunded when you took the empty back to the shop.

“It was an extra incentive,” says Hall. “And it was a much better system than having all these plastic bottles that get dumped in hedgerows or landfill sites. Even if adults couldn’t be bothered to take bottles back to the shop, it was quite a lucrative business for kids, collecting empties and taking them back and making extra pocket money.”

Incentivising recycling always has positive effects. Many years ago I visited Osaka in Japan, and went to a bar that sold beer in cans. When you’d finished you put your empty can in a slot in a huge one-armed bandit, pulled the handle, and if you got a winning combination on the reels you won a free beer dropped from the refrigerated innards of the machine.

“That’s a brilliant idea, I’m surprised nobody has taken that up here,” says Hall. “It reminds me of a scheme in Sweden where there are special bins for bottles that can be emptied by homeless people and taken to be weighed in for a payment.”

Working for a company that deals on a daily basis with waste – “We’re the waste company that hates waste!” he says cheerfully. “In a weird way, it would be good to get to the point where people were recycling and reusing so much we were out of a job!” – Hall keeps a close eye on recycling and sustainability, and a lot of it makes him angry. “I can’t believe it when you get bananas in plastic packaging,” he says. “They’re bananas! They’re already wrapped by nature!”

He’s also a little dubious about many supermarket schemes to get people off single-use plastic bag usage and thinks many of them are just to get green credentials. “Bags for life… they’re just thicker plastics, aren’t they? And tote bags or paper bags, they take energy to make. I think supermarkets could do a lot more for the environment by keeping their fridge doors shut.”

On the matter of supermarkets, whatever happened to the piles of boxes they used to leave out to put your shopping in? “Ah, there’s money in those boxes,” says Hall. “They’re not going to give them away.”

Speaking of boxes, there are a lot of lessons we can learn from the previous generation that tick them when it comes to making choices for a more sustainable future. A lot of them – fixing up broken things, repairing clothes, deposits on fizzy drink bottles – might have been driven by economic rather than ecological reasons, but the end result is the same.

And it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s a hipster fish-and-chip takeaway out there offering a small discount for anyone who brings in their own dishes and a tea towel to collect their food.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments