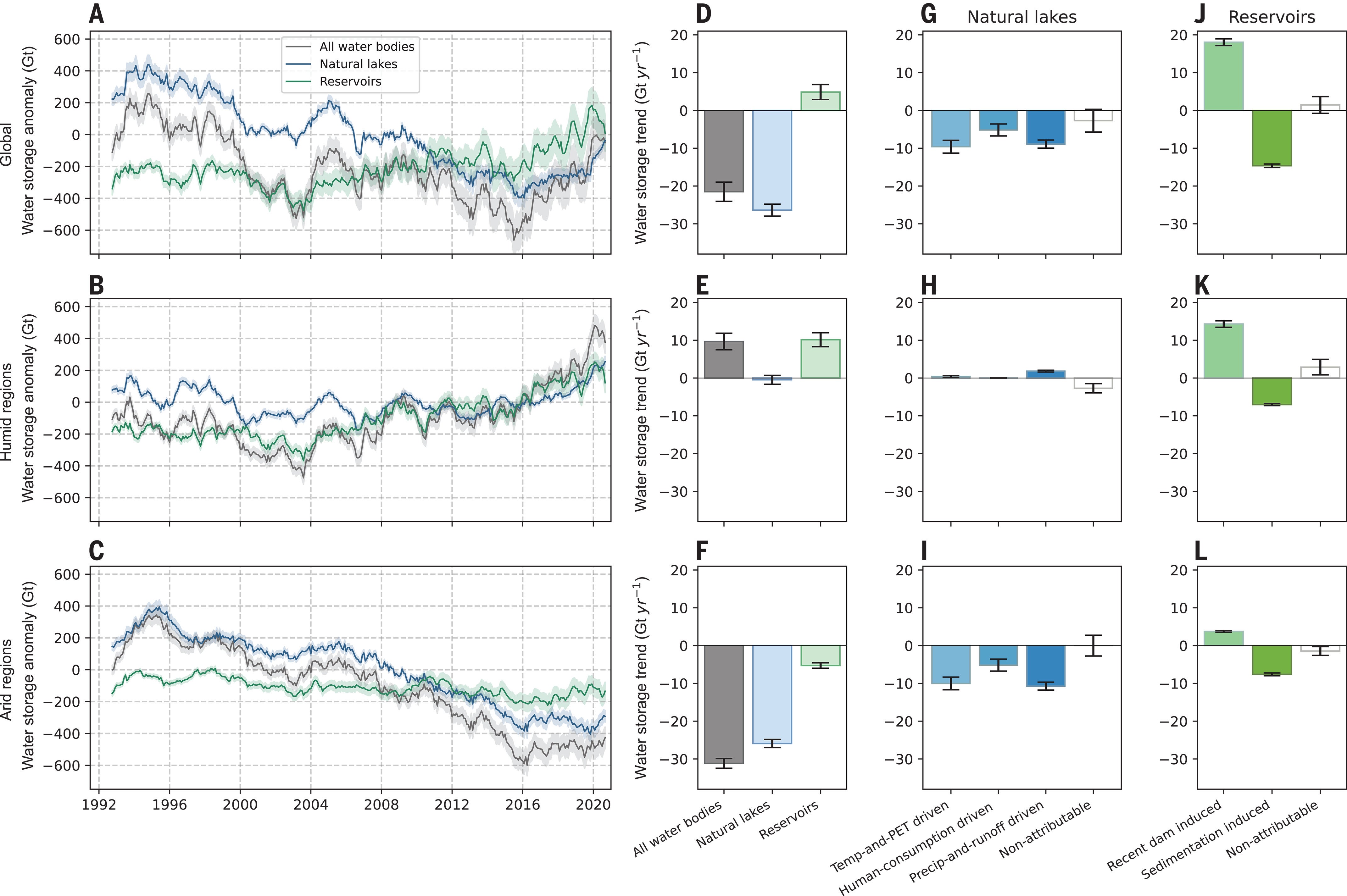

More than half of the world’s large lakes have shrunk since the early 1990s, study finds

Key freshwater sources collectively lost water at approximately 22 gigatonnes per year for nearly 30 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.More than half of the world’s large lakes and reservoirs have shrunk since the early 1990s, a new study has found.

An international team of scientists analysed almost 2,000 of the world’s largest lakes for the research, published on Thursday in the journal Science.

Using three decades of satellite observations, climate data and hydrologic models, scientists found significant storage declines in 53 per cent of these water bodies between 1992 and 2020.

Key freshwater sources, including the Caspian Sea and Lake Titicaca, collectively lost water at a rate of approximately 22 gigatonnes per year over nearly three decades, according to the findings.

That’s about 17 times the volume of Lake Mead – the US’s largest reservoir.

This shrinking of lakes poses significant concerns about water supply for agriculture, hydropower and human consumption, noted the researchers.

Fangfang Yao, a surface hydrologist at the University of Virginia who led the study, said 56 per cent of the decline in natural lakes was driven by climate warming and human consumption.

Warming formed “the larger share of that”, the scientist said.

What was surprising, however, was that even humid regions experienced significant water loss, challenging the assumption that wet areas would become wetter under the climate crisis.

“This should not be overlooked,” Mr Yao said.

Scientists identified unsustainable human water usage, changes in rainfall and run-off patterns, sedimentation, and rising temperatures as the primary drivers of declining lake levels.

The consequences of these shrinking water bodies are far-reaching, directly affecting nearly two billion people globally, with many regions already facing water shortages in recent years.

Unsustainable human water consumption led to the drying up of lakes such as the Aral Sea and the Dead Sea, the research noted.

Additionally, rising temperatures in Afghanistan, Egypt and Mongolia have intensified water loss to the atmosphere.

There were instances, however, where water levels rose, primarily due to dam construction in remote areas like the Inner Tibetan Plateau.

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need to address the effects of climate change on freshwater sources.

The world has already warmed up by 1.2C since the industrial era in 1800s due to greenhouse gas emissions, mainly from fossil fuels.

All scientific assessments reveal that the world will surpass the critical 1.5C warming threshold – set as a limit by the Paris Agreement – as early as this decade, with the latest World Meteorologist Organisation warning that it can happen within five years.

Extreme weather events are already becoming more frequent and stronger due to the climate crisis. In 2023, early heatwaves gripped Asia, Europe and Africa, while rainfall and floods have become more extreme and wildfires have destroyed towns.

If greenhouse gas emissions are not curtailed, the world is on a trajectory of reaching 3C warming by the end of the century, leading to devastating consequences for humanity.

Researchers of this report estimated that roughly a quarter of the world’s population resides in a basin of a drying lake, underscoring the necessity of incorporating impacts from the climate crisis and sedimentation into sustainable water resources management.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments