Kenya signs up to Giants Club to protect African elephants from illegal poaching trade

Some 100,000 elephants have been killed across Africa in the past three years

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

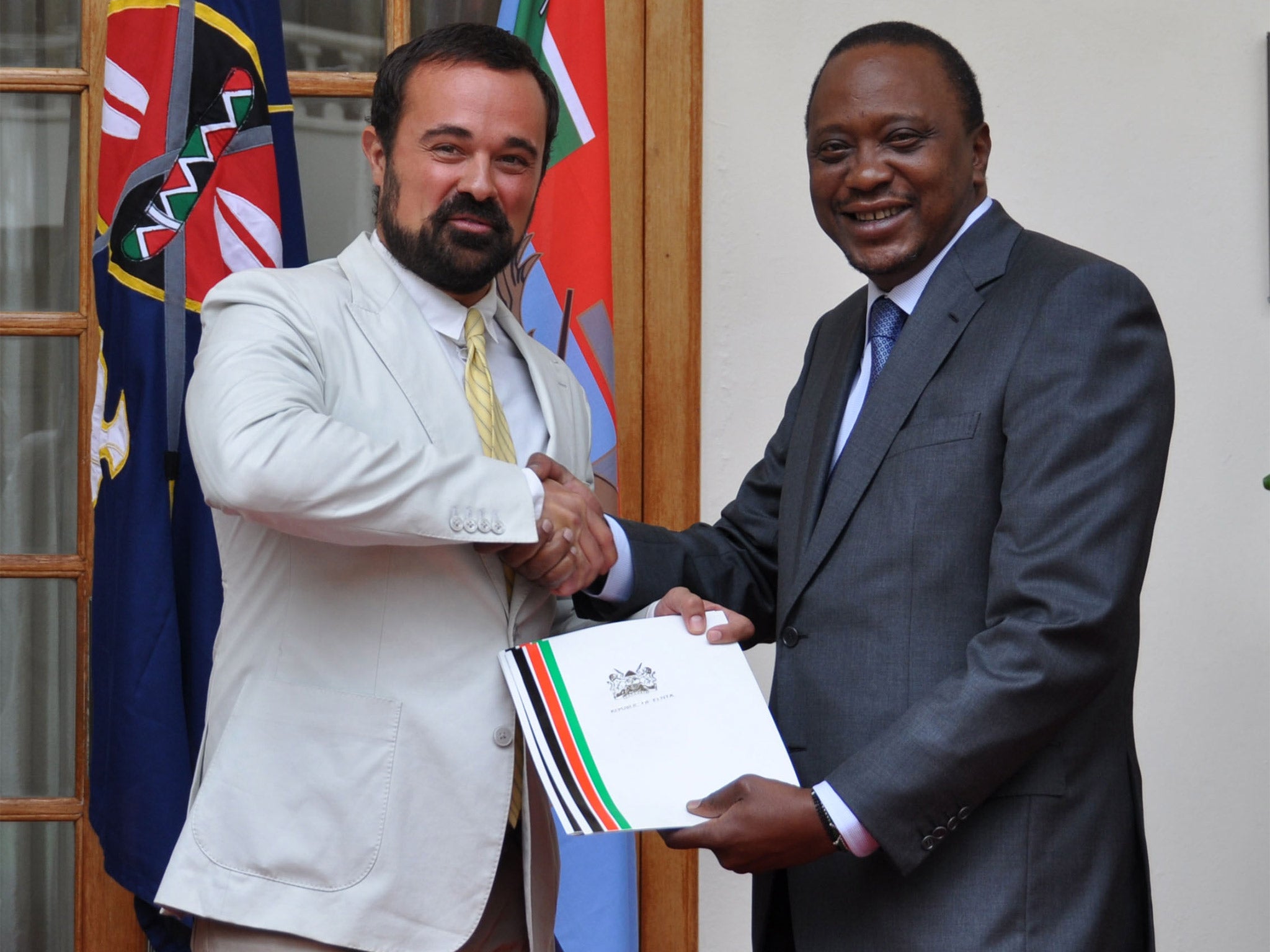

The President of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, has signed up as a founding member of the pan-African Giants Club, joining political and business leaders to combat an illegal wildlife trade that has devastated Africa’s elephant herds.

In a long-awaited move, he also committed to the Elephant Protection Initiative (EPI), which was launched in London in February last year and is supported by dozens of African countries which are struggling to eradicate the increasingly lucrative ivory trade. Some 100,000 elephants have been killed across Africa in the past three years.

“Kenya has a long history of leading the way in Africa on wildlife issues and the step made by President Kenyatta today in joining the Giants Club, and as part of that committing Kenya to the EPI, continues that great and proud tradition,” said Evgeny Lebedev, the patron of Space for Giants, which established the Giants Club, and the owner of The Independent and the London Evening Standard.

Conservationists fear that poaching, fuelled by soaring demand for ivory in the Far East, particularly China, has reached such a critical point that it threatens to tip Kenya’s elephant population into a terminal decline that could eventually wipe out its herds.

As part of the initiative, Kenya commissioned the first independent inventory of its massive ivory stockpiles, a move billed by conservationists as a crucial step in the war against illegal poaching. Judy Wakhungu, the Cabinet Secretary for the Environment, Water and Natural Resources, said that Kenya was an “exemplar” in conservation with, among other things, “the highest penalties for illegal wildlife trafficking”.

The inventory comes after an earlier pledge by Mr Kenyatta to burn the country’s entire ivory stockpile – thought to weigh more than 100 tons, among the world’s largest – by the end of the year, a symbolic action aimed at robbing it of commercial value. “We’ve got a big bonfire on the way,” said Max Graham, the chief executive of Space for Giants, adding that it will be “one of a series of fires of resistance burning across the continent”.

The ivory count, which is being led by Stop Ivory, will form the basis of a national digital register that will make it harder for ivory, as one Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) official put it, to “leak out” on to the black market.

The count is expected to take 45 days, and KWS rangers have started to measure and weigh the ivory, some tusks as heavy as 70kg, held in government warehouses. Much of it was originally destined for the Far East, where ivory and rhino horn remain coveted commodities. A kilo of ivory can fetch as much as $3,000 in China.

Kenya symbolically burnt its entire ivory stockpile in 1989 under Daniel Arap Moi, the same year that an ivory ban came into effect, reversing an elephant population decline. Ivory fell from around $300 a kilo to just $7 a kilo, bringing poaching almost to a halt.

Then, as now, conservationists wanted “to introduce the idea that ivory was worthless”, said Richard Leakey, the newly appointed chairman of KWS, and one of Kenya’s most renowned conservationists. “Ivory should only be seen as having value on an animal.”