How an army of big-headed ants saved zebras from hungry lions in Kenya

The arrival of big-headed ants ‘spells almost certain doom’, one study found

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An army of invasive ants has been so disruptive to a Kenyan ecosystem that it has changed the hunting habits of a pride of lions.

The big-headed ant species, which originated on the island of Mauritius, is one of the most invasive insects in the world, with colonies found at 1,600 locations, from East Africa to states across the US south.

In warm climates, their arrival “spells almost certain doom” for native insects, where they use their disproportionately large heads to attack other ants and cut up prey, according to a 2014 study.

Research from the University of Wyoming, published on Thursday, reveals the impact of their arrival in Ol Pejeta, a wildlife conservation area in Kenya’s Laikipia County.

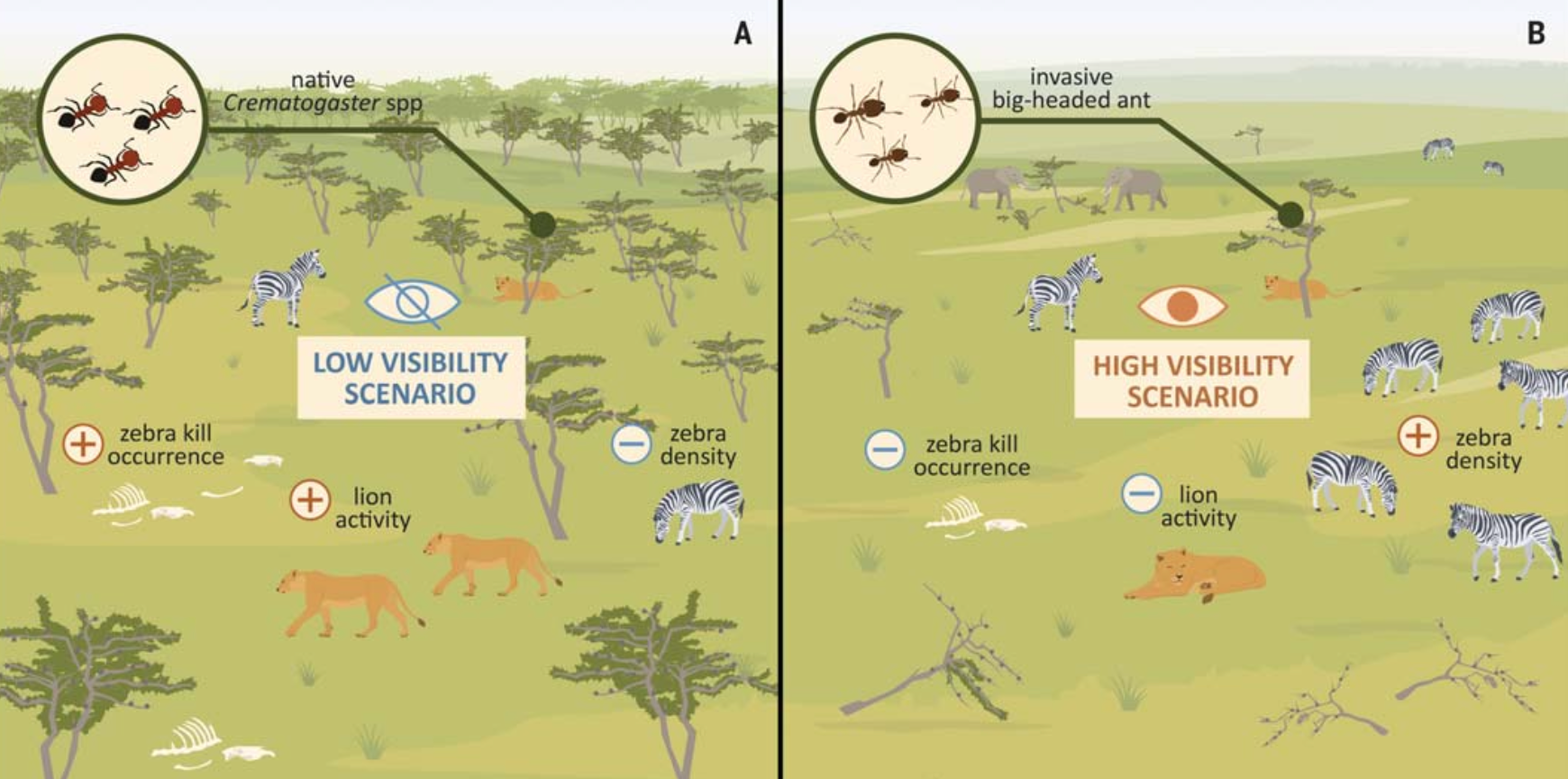

The big-headed ants disrupted the symbiotic relationship between the region’s native acacia ants and whistling-thorn trees.

The trees are the dominant species in much of East Africa, providing nectar and shelter for native ants. In turn, the ants defend the trees by emitting formic acid and biting herbivores who try to feast on them – a particularly effective strategy against elephants.

But when the big-headed ants move in, they not only kill off the native ants but also fail to protect the whistling thorns.

This allows elephants to overgraze on the trees, leaving them chewed up and broken “at five to seven times the rate in areas with invasive ants compared to areas without the invaders”.

Without the trees, the landscape is a lot more bare, leaving lions with few hiding places when stalking their preferred prey, zebras.

Ultimately, the study found that zebra kills by lions were nearly three times higher in areas that had not been invaded by big-headed ants.

While the lion population hasn’t declined in response to the insect invasion, it hasn’t been great news for the African buffalo. With fewer opportunities to hunt zebras, the lions have switched their attention to that species which are larger and harder to kill.

Over the last 20 years, the proportion of zebras killed by lions dropped from 67 per cent to 42 per cent in the area, while the number of buffalo kills jumped from 0 per cent to 42 per cent, researchers found.

“We show that a tiny invader reconfigured predator-prey dynamics among iconic species,” wrote researchers, led by PhD student Douglas Kamaru from the University of Wyoming’s Department of Zoology and Physiology.

The scientists hypothesized that the ants may end up changing the dynamics of lion prides in Ol Pejeta – but noted that the long-term consequences were unknowable as the invasion of big-headed ants continues.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments