‘Spectacular’ ancient ice age valleys reveal how climate crisis could impact glaciers

Rapid formation of enormous tunnels below ice sheets in their ‘death throes’ should be considered for today’s climate models, scientists say

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Below the North Sea, thousands of hidden giant valleys scoured out by retreating ice sheets 20,000 years ago are providing new insights into how the worsening climate crisis could impact our planet as it warms.

New research into these valleys has found they could form in "just hundreds of years", allowing the transportation of enormous volumes of water, as the ice age ended.

Today’s sea level is around 130 metres higher than it was at the peak of the last ice age.

Back then, Britain was a peninsula of mainland Europe, and large rivers such as the Rhine and the Thames were only tributaries to the river which eventually became the English Channel.

As the ice receded, it unleashed huge volumes of water – sometimes unevenly, which reshaped the landscape.

The new research shows the scale and the speed of a process of intense erosion beneath the ice sheets which is believed to have helped funnel melt water away from them, helping prevent a more rapid collapse.

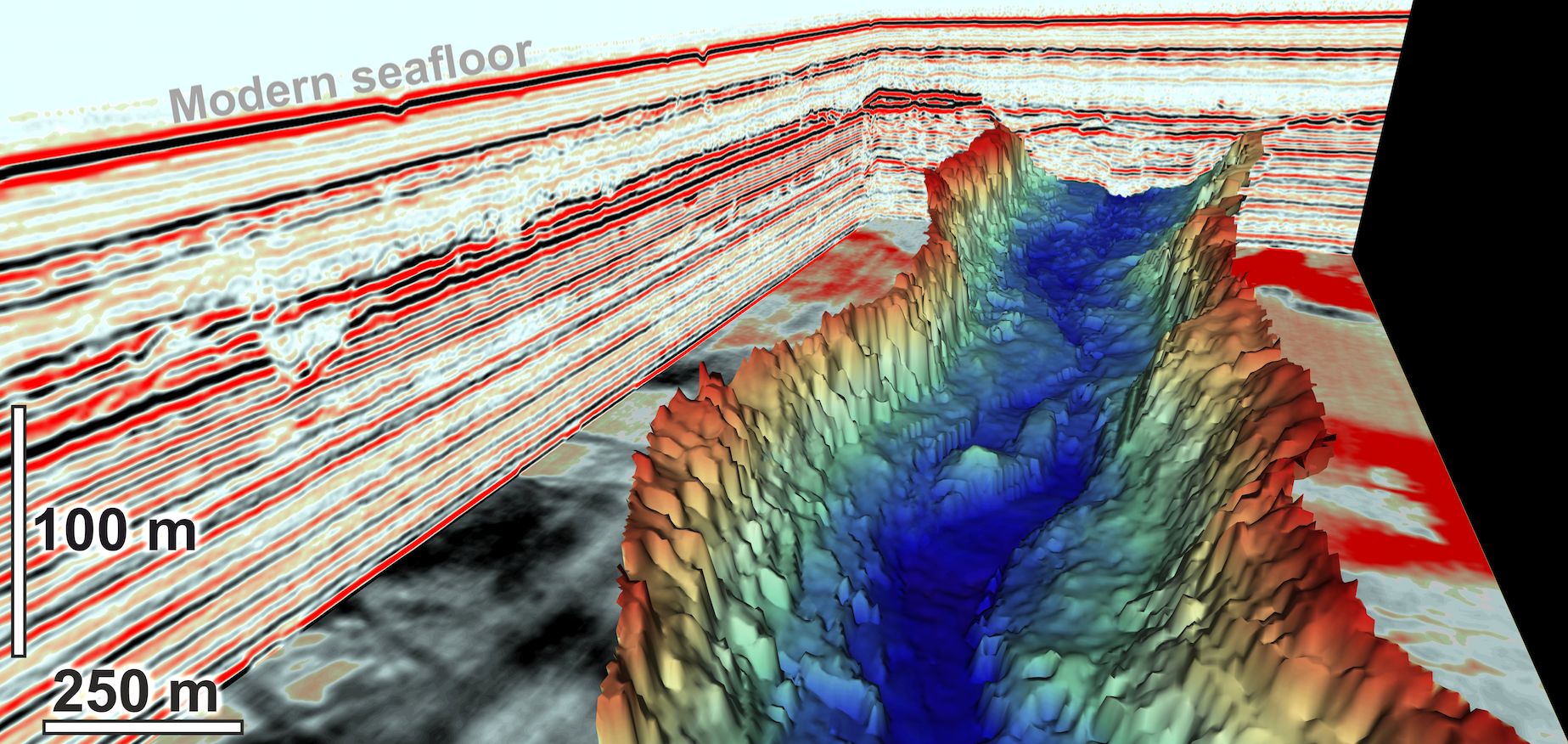

The scientists said these tunnel valleys, found beneath the modern seabed, can be up to 500 metres deep, 5km wide and 150km long – making each of them several times larger than Loch Ness.

Lead author James Kirkham, from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the University of Cambridge, said: “This is an exciting discovery. We know that these spectacular valleys are carved out during the death throes of ice sheets.

"By using a combination of state-of-the-art subsurface imaging techniques and a computer model, we have learnt that tunnel valleys can be eroded rapidly beneath ice sheets experiencing extreme warmth.”

The team said they analysed "jaw-droppingly detailed" seismic images which provide a 3D scan of the Earth’s buried layers.

Informed by "delicate clues" discovered within the valleys, the authors performed a series of computer modelling experiments to simulate valley development, and test how quickly they formed as the last ice sheet to cover the UK melted away at the end of the most recent ice age about 20,000 years ago.

The researchers said the "surprisingly fast rate" at which these tunnel valleys form means scientists must start considering their creation and effect on models used to understand how today’s ice sheets may be impacted over the coming decades and centuries.

"There are no modern analogues for this rapid process", the authors said, but these ancient valleys, now buried hundreds of metres beneath the muds of the North Sea seafloor, record a mechanism for how ice sheets respond to extreme warmth that is missing from present-day ice sheet models.

The models do not currently resolve all water drainage processes, despite them appearing to be an important factor influencing future ice loss rates and ultimately sea level rise around the world.

Mr Kirkham, a PhD student, said: “The pace at which these giant channels can form means that they are an important, yet currently ignored, mechanism that may potentially help to stabilise ice sheets in a warming world.

"As climate change continues to drive the retreat of the modern-day Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets at ever-increasing rates, our results call for renewed investigation of how tunnel valleys may help to stabilise contemporary ice losses, and therefore sea level rise, if they switch on beneath the Earth’s ice sheets in the future.”

Dr Kelly Hogan, co-author and a geophysicist at BAS, said: “We have been observing these huge meltwater channels from areas covered by ice sheets in the past for more than a century but we did not really understand how they formed.

"Our results show, for the first time, that the most important mechanism is probably summer melting at the ice surface that makes its way to the bed through cracks or chimneys-like conduits and then flows under the pressure of the ice sheet to cut the channels.

"Surface melting is already hugely important for the Greenland Ice Sheet today, and this process of water transport through the system will only increase as our climate warms. The crucial question now is will this ‘extra’ meltwater flow in channels cause our ice sheets to flow more quickly, or more slowly, into the sea.”

The team said the research highlights an overlooked process that can rapidly switch on beneath melting ice sheets. Whether these channels will act to stabilise or destabilise the Earth’s contemporary ice sheets in a warming world remains an important and open question.

The research is published in the journal Quarternary Science Reviews.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments