Tropical forests 'empty' as illegal hunting slashes large mammal populations, study warns

Key species are being wiped out by hunters looking to collect valuable horns and bones

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Illegal hunting is causing catastrophic declines in mammal populations living in the world’s remaining tropical forests, a new study has warned.

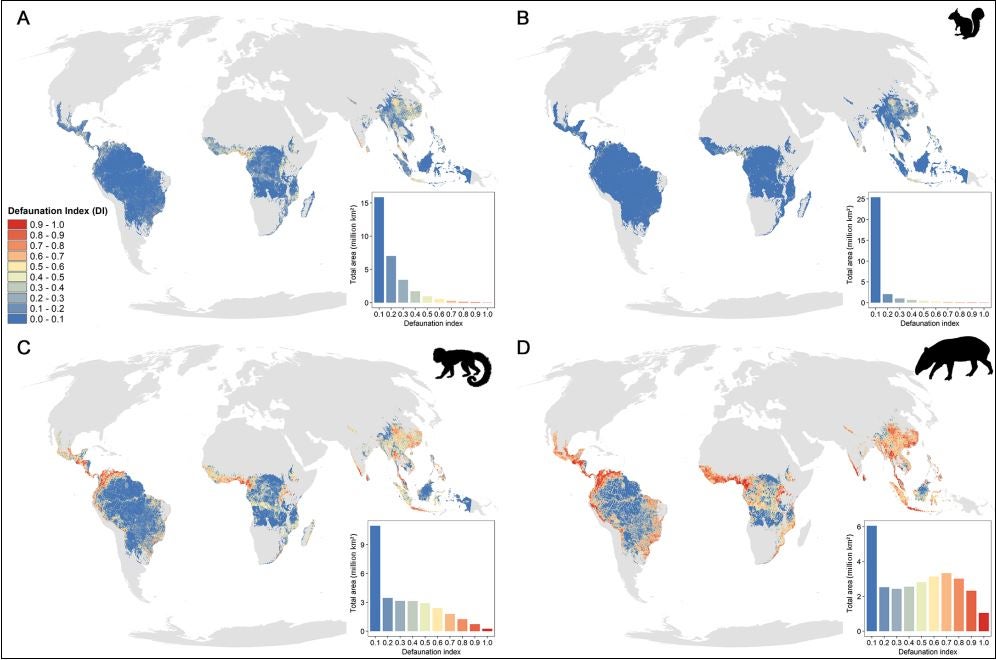

Jaguars, leopards, elephants and rhinos have seen population declines of 40 per cent in just 40 years and the study warned that hunting – half of which is done illegally – has left many tropical forests "empty" of wildlife.

Even the world’s most pristine jungles are having their ecosystems damaged as key species are wiped out by hunters looking to collect valuable horns and bones, an international team of researchers lead by the Radboud University in Holland, found.

Within the tropics, only 20 per cent of remaining habitats are considered intact.

“Without adequate measures wildlife hunting will increase in the future,” lead researcher Dr Benítez-López told The Independent.

“Our calculations show that even in protected areas mammal populations could be under hunting pressure, particularly in Western and Central Africa, and South East Asia. If projections of human population growth for Africa are true, the demand will continue to increase. Plus there are many roads planned that will traverse tropical forests."

Until now there were vast understudied areas in the tropics where hunting impacts on mammal communities were unknown, according to the study which is published in the Plos Biology journal.

The biggest declines were seen in Western Africa, with more than 70 per cent population reductions. Researchers found primates and pangolins were most at risk.

Declines have largely been caused by increased human accessibility to remote areas.

Dr Benítez-López said: “Hunters target primarily large-bodied species because they provide relatively large meat yields and commercially valuable by-products such as horns and bones. In addition, large mammals reproduce at slow rates, which means that it takes longer for their populations to recover when exploited.”

The study estimated the impact of hunting on 4,000 mammal species in the tropics. More than half of tropical forests are under pressure from hunting.

Dr Benítez-López said: “Hunting of carnivores may lead to an increase in herbivores with negative consequences for the vegetation whereas the hunting on species that feed on fruits and disperse their seeds can have negative consequences on forest regeneration”

The decline of mammals may have profound implications for ecosystem functioning.

“In the tropics habitat loss due to land use change (deforestation and conversion to croplands or rangelands) is still the leading cause of defaunation, yet hunting has comparable effects and, more importantly, it is responsible for massive declines in animal populations in seemingly undisturbed forests,” said Dr Benítez-López.

“Even forests that are considered intact according to satellite images – in which there is no visible deforestation or logging – could be partially defaunated.”

Rural communities who rely on wild meat for their food may find their main source of protein disappearing.

“Hunting effects were to this point not considered in large-scale biodiversity assessments and our results may help to fill this gap and to eventually produce more representative estimates of human-induced biodiversity loss,” she said.

The study looked at more than 3,200 data estimates from the last 40 years. It included more than 160 studies and hundreds of authors studying around 300 mammals across the tropics.

Researchers say this new study should help inform species extinction risk assessments and conservation planning.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments