‘The first step in a long journey’: The pioneering British town which has committed to veganism

A West Sussex commuter town is encouraging its 34,000 residents to drop animal products from their plates to help fight the climate crisis. Jane Dalton meets some of them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In many ways, Haywards Heath is an unremarkable British town.

Positioned in West Sussex on the main Brighton-to-London railway line, it is popular with commuters to the capital but also has an ample elderly population. Charity and coffee shops thrive, but in recent years the town has lost its high street branches of Santander, Currys, Co-op and Dorothy Perkins, and is no stranger to a planning battle.

So far, so average.

But Haywards Heath also just happens to have made history with a pioneering step in the fight against the climate crisis.

The town council has signed up to the plant-based treaty, an initiative aimed at persuading world leaders to drive societies gradually to switch away from diets involving animal products to diets without – otherwise known as vegan food.

Experts agree that animal agriculture is a leading cause of the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, partly because of its high emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, and partly because it uses drives deforestation as habitats are cleared for livestock and animal feed – land that could produce more food for people if used for human-edible crops.

It also drives biodiversity loss and water pollution, and high consumption of animal products has been linked to heart disease and cancer.

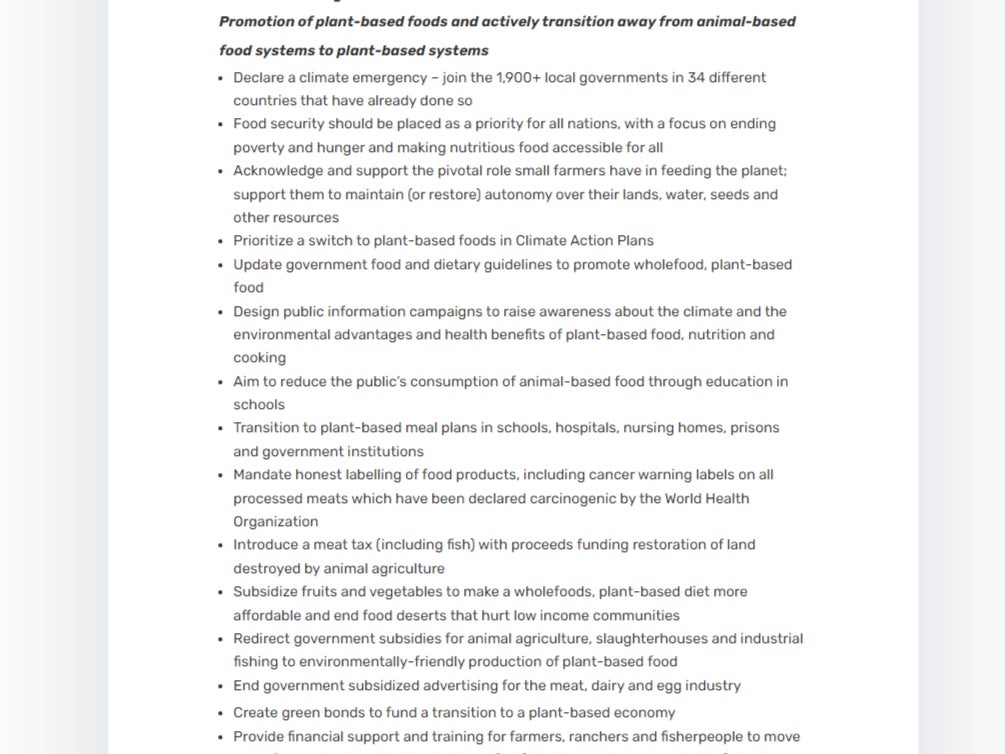

The treaty’s demands – 38 of them in all – range from no building of new animal farms and no intensification of farms to transitioning to plant-based meal plans in schools, hospitals and nursing homes, as well as subsidising fruit and veg.

Grants would be given to livestock farmers for switching to plant production, while food security would become a priority for all nations, “with a focus on ending poverty and hunger”.

So far, 17 cities worldwide have endorsed the treaty, including Boynton Beach in Florida.

But the modest town of Haywards Heath, which is home to around 34,000 people, is the first place in Europe to do so.

As a vegan journalist who lives locally, I had to know more about what this meant. So, on a morning sticky with the humidity of a heating planet, I set out to find out what it would mean in practice – and how other residents would respond.

For a place to officially support the treaty, local councillors must vote it through, and an endorsement is essentially a call for the UK government to negotiate a global plant-based treaty.

In Haywards Heath, the practical steps will begin with environmental awards for schools and businesses that reduce food waste and encourage vegan eating, and the town council will provide materials for schools to inspire the next generation to reduce its greenhouse gas footprint.

Richard Nicholson, a Green Party councillor who convinced the council to agree to the endorsement, admits the move won’t halt damaging emissions quickly – nor even change everyone’s minds. “It’s the first step in a long journey,” he says. “But we’re taking it as a cornerstone of future policy.”

Cllr Nicholson persuaded the council to support Veganuary, when restaurants and supermarkets were supported in nudging customers away from meat and other animal products, and he hopes the same will happen again.

Heading into Waitrose, Mike Bellew, 76, was not open to persuasion. “I like meat too much,” he said. “And I think there are far better ways to tackle climate change – there’s the amount of travel people do. And changing gas and oil to renewables.”

But his wife, Sheila, 78, said: “I can do without meat. There are days I don’t want to eat meat. Just because I don’t like the taste some days. But I agree about cutting down on travel. We’ve not been away since before Covid.”

Taking a break from the office on a park bench, paralegal Eugenie Clark, 23, said she wouldn’t go vegan right now and doesn’t normally give much thought to vegan food, but she said perhaps she should – although it would need to taste good for her to be convinced.

But accountant Esther Holden is “more or less” plant-based already, eating meat only rarely, and sees colleagues starting to cut down on meat.

“My parents were environmentally minded, even back in the 1970s and 1980s,” she says. “I probably would be happy to go vegan but it’s whether I could persuade the rest of the family because I don’t want to be making lots of meals. The children are really good at eating vegetables so they wouldn’t complain too much.

“I talk about it a lot with colleagues. People are starting to think about it now, especially with the drought. It’s a pity everyone didn’t think about it decades ago.”

As for unshakable meat-eaters, she says: “There are lots of things we like but it doesn’t necessarily mean we have to do it.”

Her husband, Lee, 41, has a lot of days when he eats vegan, and only a love of cheese stops him from doing it full-time. The couple have a teenage daughter who has a dairy allergy and is vegan because “she hates the idea of processed, cheap meat”.

Further up the street, recruitment director Richard Coleman, 45, says: “I enjoy a steak too much. I do enjoy eating meat.” The idea won’t take off because people want choice, he suggests.

An endorsement of the plant-based treaty is similar to a climate emergency declaration, says Nicola Harris, a UK coordinator of the initiative, whose colleagues are working to also win endorsements from New York to Mumbai.

She cites a study referenced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that showed that if a vegan diet was adopted globally, it would reduce land use for agriculture by 75 per cent.

“For example, it takes almost 100 times as much land to produce 1 gram of protein from farming cattle as peas or tofu,” she says.

On my way back, I stop a lady leaving Waitrose with her young son. As chance would have it, creative director Cat Turner already follows a vegan lifestyle and is delighted by the town council’s move.

“A plant-based diet is ultimately good for everyone – it’s better for the environment, better for children growing up understanding where their food comes from,” she says. “Its becoming more normalised is really exciting for me.”

Ms Turner, 39, adds: “There are no downsides – none. We’ve seen a lot of resistance over the years from the dairy industry or those farming meat – it’s terrifying for them because it’s their livelihood but if there’s a way that they can come in on the journey, it’s really exciting. I’m really proud of Haywards Heath.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments