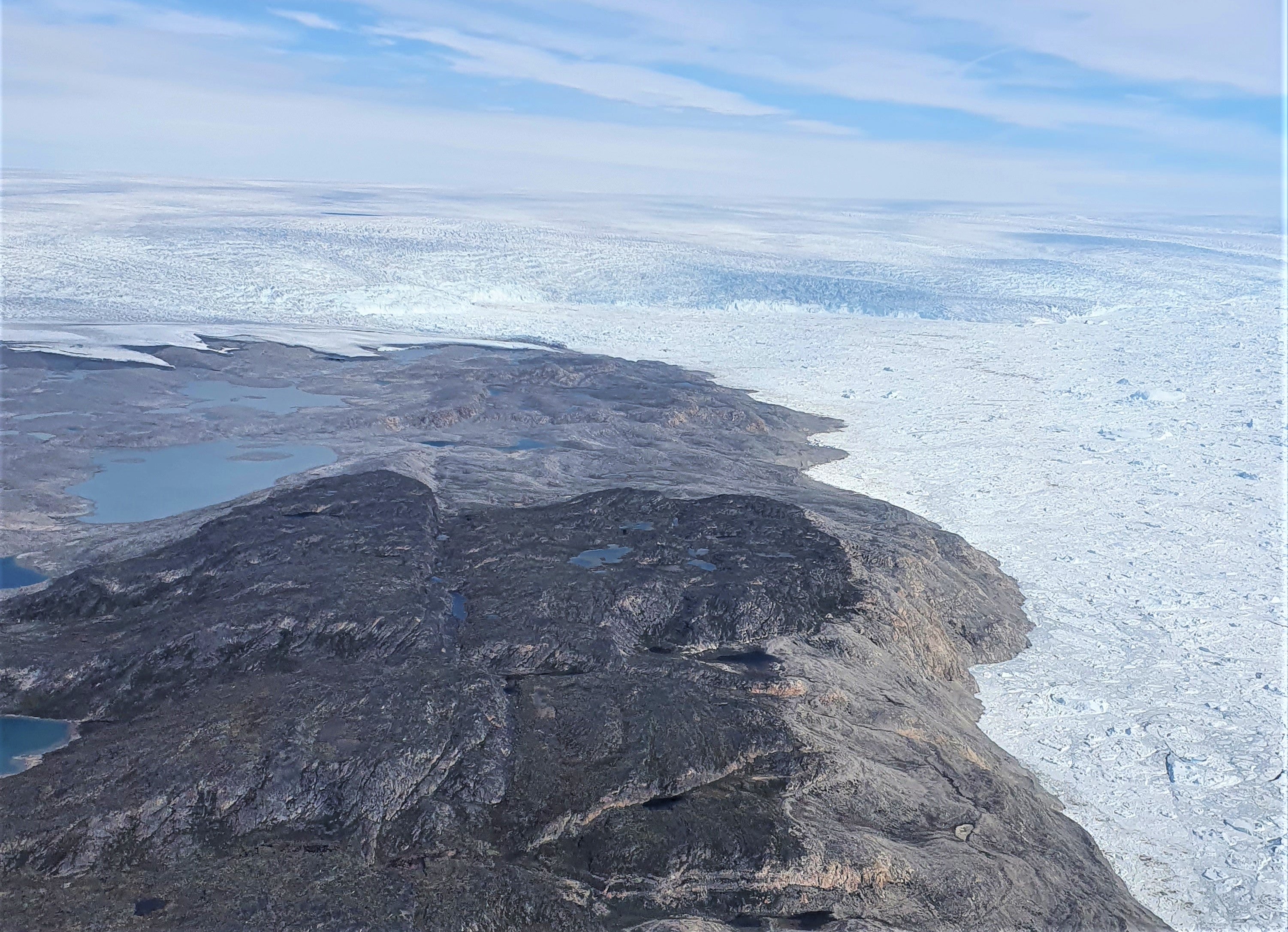

Greenland’s largest glaciers nearing rates of melt expected in ‘worst-case scenario’

Greenland’s three biggest glaciers added the equivalent of around 8mm to global sea levels from 1880 to 2012, study says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Greenland’s largest glaciers are currently melting at levels close to what scientists had previously expected under a future “worst-case scenario”, a study has found.

Using a combination of aerial photographs and field data, the study found that current rates of mass loss from Greenland’s three largest glaciers are higher than once thought.

The melting of these three glaciers added the equivalent of around 8mm to global sea levels from 1880 to 2012, according to the research.

Previous research had estimated that the same three glaciers would contribute 9-15mm to global sea levels by 2100 under a “worst-case scenario”.

The Greenland ice sheet is a mass of frozen freshwater sitting on the island of Greenland that is around 1.7m square kilometres in size. This is about three times the size of Texas.

As a result of climbing air and ocean temperatures, the ice sheet is losing mass each year. The loss of mass from Greenland’s glaciers is, in turn, causing sea levels to rise.

The research, published in Nature Communications, focuses on the “big three” glaciers in Greenland: Jakobshavn Isbræ, Kangerlussuaq Glacier and Helheim Glacier. These glaciers together hold enough ice to raise sea levels by around 1.3 metres, if they melted completely.

It found that the amount of sea level rise from the melting of these three glaciers is already nearing rates previously expected under a future “worst-case” scenario.

This suggests that, if the world were to see extremely high emissions in the coming decades, ice loss from Greenland’s glaciers would be considerably higher than previously projected, explains study author Prof Jonathan Bamber, a glaciologist at the University of Bristol.

“The warming that induced that mass loss of Greenland [over the 20th century] was about 1.5C,” he told The Independent.

“The worst-case projections of warming over the next century are much higher than that, more like 8.3C for the Arctic by 2100.”

When making projections for the future, scientists use a range of different possible climate change scenarios.

The “worst-case scenario”, called RCP8.5, assumes that very little is done to tackle global emissions over the 21st century, causing global average temperatures to rise by around 3.7C, when compared to temperatures from 1986-2005.

(Scientists have previously pointed out that this scenario is not the most likely for Earth’s future, and should not be misinterpreted as a “business-as-usual” scenario.)

Though the world would see an average of 3.7C of warming in a worst-case scenario, the temperature rise seen at Greenland and the Arctic Ocean is expected to be much higher, said Prof Bamber.

This is because of a phenomenon known as “polar amplification” – a term used to describe how the Arctic is heating up at a faster rate than the rest of the world.

One of the leading drivers of polar amplification is the melting of Arctic sea ice.

Warming of the world’s oceans and atmosphere is causing sea ice to melt at an astonishing rate. Bright white ice reflects away sunlight, and, once it disappears, the exposed dark ocean begins to absorb more sunlight, heating the ocean further – leading to further ice melting. This “feedback” is causing the Arctic region to heat up at a rapid rate.

The study did not investigate whether rates of glacier melt from Greenland’s glaciers would also be higher than expected under more optimistic climate change scenarios.

However, “it is highly likely they are underestimated for these other scenarios” as well as for the worst-case scenario, Prof Bamber said.

The findings add to what is known about how the climate crisis is affecting the Greenland ice sheet, says Dr Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute, who was not involved in the new study, told The Independent.

“[The study] is in line with quite a few studies that have been published recently showing that sea level rise from ice sheets is following the highest emission scenario, though here they suggest that even that may be an underestimate,” she said.

“They also point out that for at least these three glaciers the ‘dynamic component’ of ice loss is by far the most important – that is the loss of ice by calving of icebergs.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments