Great white sharks - the misunderstood giants with a softer side

'Yes, it’s dangerous, but they are not mindless killers'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

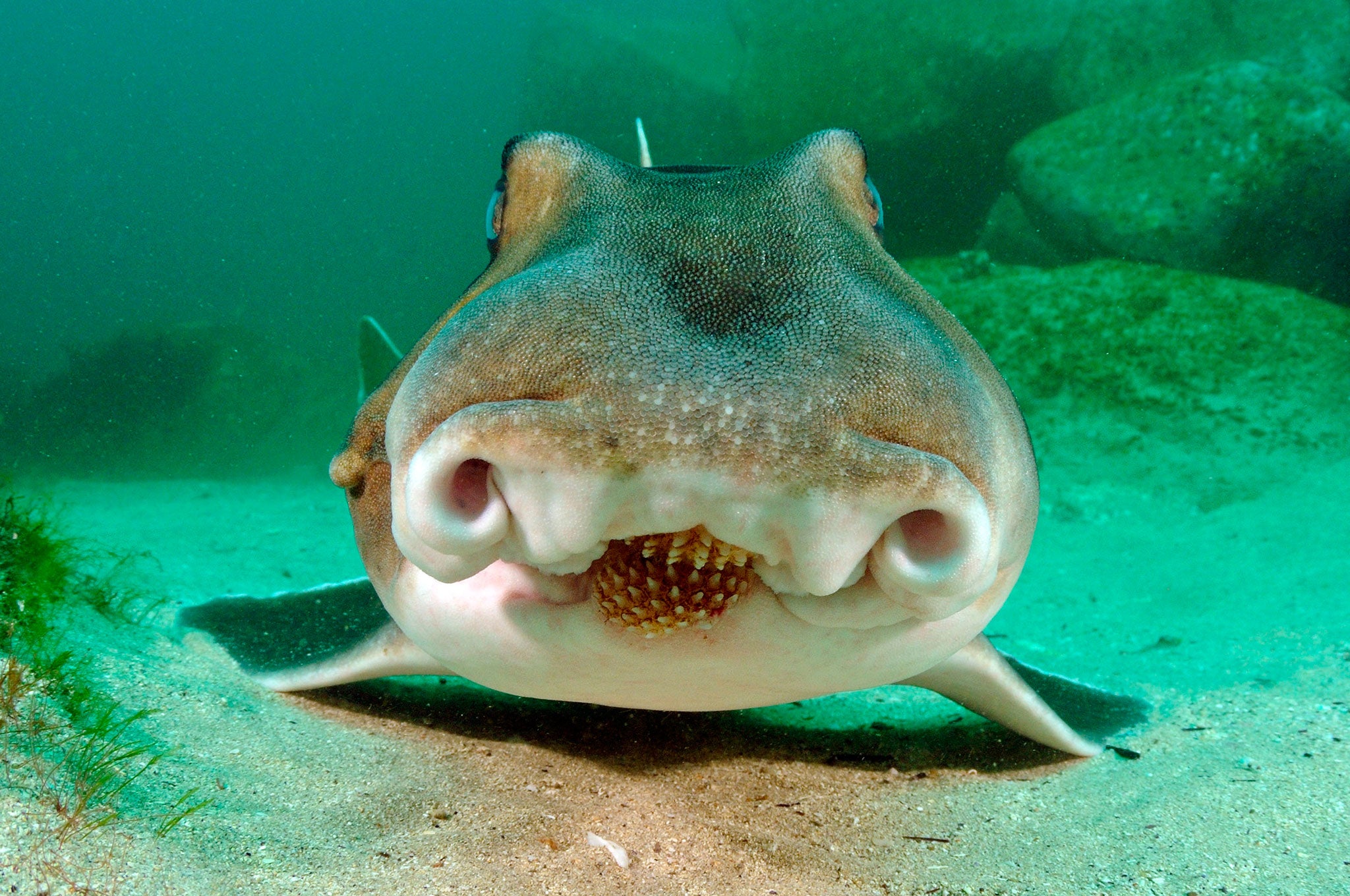

Your support makes all the difference.How should you behave if you invade a great white shark’s personal space? Politely, according to underwater cameraman Morne Hardenberg, who has helped to reveal the gentle etiquette of the oceans’ top predators in a pioneering new wildlife series by the BBC. “You don’t turn your back on a white shark and swim away from it – that’s a trigger. All its food swims away from it,” says Hardenberg, 38, one of the few naturalists who dares to dive with them outside of a cage.

“When they’re interacting with you, they don’t like you stopping and breaking off the interaction. The animal you meet can be very curious, it finds you very interesting.

“Sometimes it’s coming into your space. You can’t just bolt. You have to react the same way they would: swim after the shark and show a threat. It’s a chess game. They make a move, you make a move, and sometimes the moves can become a tense situation. Yes, it’s dangerous, but they are not mindless killers.”

Since giving up his job as an IT technician 16 years ago, the South African has studied the behaviour of great whites, with surprising findings. “In the beginning I was very afraid,” he says. “But they have a softer side that most people don’t get to see.”

By diving outside a cage, Hardenberg’s team have captured footage of great whites greeting each other and communicating, as well as placidly interacting with humans.

Shark, the new trilogy from the BBC’s renowned Natural History Unit, vows to do nothing less than rehabilitate the creatures’ image, 40 years after the release of Jaws.

We know little about sharks: it is difficult to study an animal that never surfaces to breathe. So we’ve only seen a limited repertoire of shark behaviour, mostly great whites hunting at the surface. Nothing about courtship, parenting, communication or socialising; and little about the 509 other known shark species, not to forget their cousins, the rays. While there are spectacular chase scenes in Shark – including the first great white attack filmed from the sky, below and at the surface – this series shows how they are picky eaters and frightened by humans.

In an age where we like to think we are scaling the peaks of human knowledge, sharks remind us, through their mystery and longevity (400 million years), of our insignificance in the cosmos, of the discoveries still awaiting us on our planet. They are a symbol of humanity’s unquenched thirst for knowledge, an inspiration to cross the liquid frontier.

The best wildlife filmmaking reveals nature in a way that we haven’t seen it before. Here, we meet sharks that can walk on land, juvenile sharks with best friends, mothers who travel thousands of miles to give birth to their pups in the same place they were born. The fastest shark, the mako, races a speedboat. Scalloped hammerheads dance to win a mate, black-tips stage a violent underwater opera worthy of Tarantino, and a huge manta ray encounters a human for the first time (probably).

We learn about sharks’ surprising potential to help mankind, from motoring to medicine. Research into fighting MRSA, cancer, Alzheimer’s, heart attack and stroke currently benefits from breakthroughs made by studying sharks. Sharks also have personalities and live rich and complex social lives. They are fast learners and build maps in their heads allowing them to accurately navigate vast distances.

When you dive with big sharks – and I’ve dived with tiger, bull and great hammerhead, among others – it’s surprising how uninterested they are in you. Most ignore you or are too timid to approach. “A lot of films about sharks have focused on predation, hype and scariness,” says series producer Steve Greenwood. “We wanted to present all aspects of their lives. The trial of life is common to all creatures: courtship, mating, birth, parenting, growing up, finding food and keeping clean.” The BBC2 controller Kim Shillinglaw had told her team: “I don’t want a predation series.”

In one of the most extraordinary sequences ever filmed by the BBC’s Natural History Unit, a scene of exquisite beauty, a quarter of a million mobula rays meet in a single shoal. These friendly winged giants gather once a year off the coast of Baja, Mexico, and as dawn breaks, the scale of their encounter is revealed.

Rarely has the enigma of life in our oceans been so movingly captured. No one knows why the rays meet. We think it’s courtship. To stand out from the crowd, these show-offs leap high out of the water, trying to make the noisiest belly flop when they land. The bigger the bang, the better the chances of impressing a mate. Only the most stylish and ostentatious extroverts win this spectator sport. Some even try back-flips. After the jumping subsides, the rays disperse again. How many other surprises await us beneath the oceans’ surface?

No shark is more misunderstood than the great white, and technology allowed the BBC cameramen to get closer than ever before to capture a more intimate portrait. Although the team filmed in ultra-HD for the first time underwater, the real tech breakthrough was the use of “re-breathers”. These air recycling units allow you to dive deeper, for longer, and without releasing bubbles, which scare off even big sharks. It’s the marine equivalent of being in a birdwatcher’s hide, allowing naturalists to get nearer the animals and observe them at length.

We are only starting to interpret great whites’ sophisticated communication. Cameraman Hardenberg now understands it better than most. “We look for subtle body language changes to know when to break off the interaction,” he explains. “When a shark drops its pecs [pectoral fins] it’s going to start moving fast. That can be because it’s scared rather than aggressive. When the shark’s agitated you see body spasms run along its back. When it gapes, opening and closing its mouth, it’s feeling uneasy. If the back arches, again, that’s agitation.” He prefers to dive with the biggest white sharks, over five metres, because they tend to be more relaxed.

Great whites are solitary, unlike other more sociable sharks, and go months and sometimes years without seeing another of their kind. So the BBC team wanted to find out how they react when they first see each other, and how they avoid deadly conflict. The answer appears to be by showing great courtesy. About 150 great whites gather near the Pacific island of Guadalupe every year. They keep the peace using respectful body language, and avoid conflict whenever they can.

“This footage will flip the switch on people’s underst-anding,” says Dr Alison Kock, research manager of Cape Town’s Shark Spotters Programme. “It shows the white shark as slow, graceful and relaxed in the water.

“What you’ve seen on TV before just isn’t real – those pictures of sharks with their mouths wide open. What you didn’t get told is that it took months to get that footage.”

Dr Kock has witnessed over 3,000 attacks on seals and devoted her career to reducing conflict between humans and sharks. Cape Town is unique in having a large population of great whites next to a big city of four million people, plenty of whom like to surf or swim. Electric cables are being trialled as a deterrent off one beach, while HD cameras have the potential to spot sharks more keenly than the human eye. But she says it’s easier to change human behaviour and has discovered patterns in white shark activity at low light (dawn, dusk, overcast days) near particular beaches. Avoid these times and places and you dramatically reduce the chance of meeting a toothier swimmer.

Satellite tagging has proved great whites’ lack of interest in people: individual sharks have stayed close to a beach for 28 days at a time – and yet there are few encounters.

“We don’t say white sharks are not dangerous animals,” she adds. “You still have to respect them for the super-predators that they are when you enter that food chain. If you make a mistake the predatory nature of the shark is going to come out.

“It’s tragic when an attack happens, but given the amount of time they spend close to beaches, they’re not targeting us.”

During the BBC team’s 2,600 hours underwater with sharks, there wasn’t a single shark incident, not a nibble. Assistant producer Rachel Butler, who was responsible for safety on some of the dives, explains: “I thought the most dangerous element would be the sharks. But it was the cold under the ice, the depth in the shipwreck [causing nitrogen build-up in divers’ blood], the current in Palau which could have pulled the divers out to sea. The real dangers were hardly ever the sharks.”

An estimated 100 million sharks are killed every year by commercial fishing, mostly for shark fin soup. Sharks predate the dinosaurs but cannot evolve quickly enough to survive finding themselves on Chinese lunch menus. They are critical to the marine food chain and the humans who rely on it: when sharks disappear, predators in the middle can proliferate and destroy fish stocks.

We are at the dawn of understanding sharks, still answering basic questions about how many there are and where they live. Some of the latest discoveries could benefit us.

Sharks are built for speed, with a powerful tail and sleek curves, but it’s their skin which humans are copying: the microscopic edge reduces drag. This texture has been copied to make faster cars, planes and swimsuits. And because almost nothing can stick to it, including bacteria, it’s being trialled in hospitals and on touchscreens to halt the spread of superbugs such as MRSA.

Hidden in the kelp forests off Santa Barbara, California, is a shark that could save human lives by transforming our understanding of cancer and Alzheimer’s. The swell shark glows bright green in moonlight. The chemical that fluoresces its skin can be used to track unhealthy cells around the body, to help understand how diseases develop and which drugs effectively treat them.

Then there’s the epaulette shark – the only shark that can walk. This creature gets stranded on coral when the tide falls, but can walk back into the sea using its fins as feet. Professor Gillian Renshaw, of Queensland’s Griffith University, has been studying the epaulette to learn how we can minimise brain damage in humans after a heart attack or stroke, two of humanity’s biggest killers. How do the organs of a stranded epaulette survive oxygen starvation? The answer could lead to therapies that save human lives.

“This is a golden age of scientific endeavour to understand sharks,” says Mike Gunton, the executive producer. “Increased awareness of the wonders of the animals – and the perils they face – feed into efforts to conserve and manage. We’ve seen that with whales, with cod. Sharks will always fascinate people. They are the ultimate predator on the planet.”

’Shark’ starts on BBC1 at 8.55pm next Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments