The climate crisis is aggravating 58% of infectious human diseases, including typhoid and Zika

Climate hazards like floods, droughts and storms spread diseases and leave people less prepared to cope, a new study finds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2016, a community in a remote corner of northern Siberia started to get sick.

Dozens of people, and thousands of reindeer, had developed anthrax, a bacterial disease that can cause fever, swelling and vomiting. One child died, as well as at least 2,000 reindeer.

The cause is believed to be the climate crisis.

Scientists think that extraordinarily high temperatures that summer thawed out a frozen reindeer carcass that died from anthrax decades before – releasing dormant spores back into the air with tragic consequences.

It’s not the only time the climate crisis may have gotten people sick. A new study found that 58 per cent of human infectious diseases have been helped along by climate-related disasters, from bacteria like anthrax to viruses like Zika and parasites like malaria.

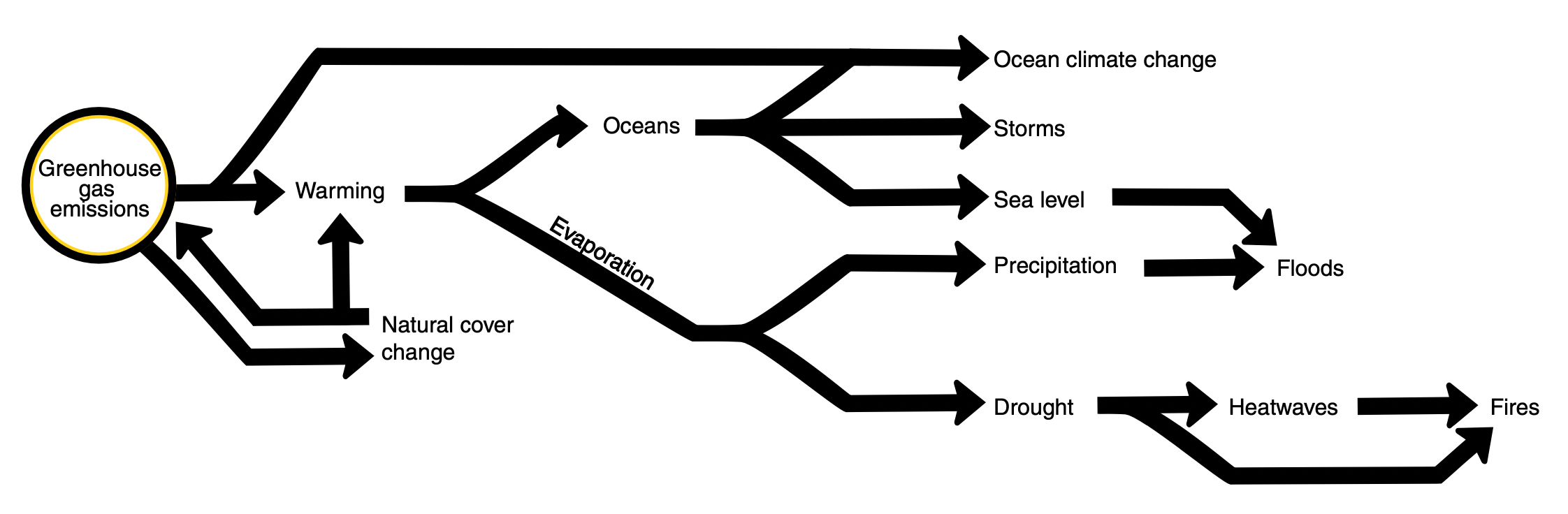

The results highlight some of the secondary consequences of climate disasters as floods, storms and droughts push people into contact with disease.

The sheer magnitude of the potential climate impact on disease means this problem may only be fixed by attacking it at the source, study author Camilo Mora, a geographer at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, tells The Independent.

“We need to forget about the idea of adapting to climate change,” Dr Mora says. “We need to move right away to reduce emission of greenhouse gases.”

To do this research, the team gathered information from hundreds of research papers that documented the connection between a climate hazard and a disease. They noted all the different ways that floods, warming and storms, for example, were connected to different pathogens.

Results were published on Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Some connections between climate and disease are rather straightforward. For example, flooding can lead to cases of leptospirosis, a bacterial disease, contracted when people wade through infected waters.

But flooding can also lead to long-term standing water, which provides fertile habitat for mosquitoes and spurs associated diseases like dengue, chikungunya and malaria.

Some disease pathways are more indirect but still related to the climate crisis.

For example, after a disaster hits a community, the subsequent lack of access to adequate healthcare could increase the spread of venereal diseases like gonorrhoea, the study authors note.

In addition, some scientists believe that heatwaves could make viruses more adaptive to high temperatures, and thus less susceptible to the body’s fever response, the authors note.

The connection between the climate crisis and disease wasn’t entirely one-sided — the study found that 16 per cent of human infectious diseases could be alleviated by climate impacts. After a drought, for instance, there might be fewer pools of standing water, meaning less malaria.

But the reverse is also true. With malaria, for example, drought can also lead to higher mosquito density in the water pools that remain, the authors point out.

Dr Mora says he was surprised by the sheer number of ways that climate hazards have influenced human diseases. The paper found that there are over 1,000 ways that the climate crisis could aggravate infectious diseases — which the authors have visualized in an interactive website.

That exhausting list is why he says we need to focus on the source problem: stopping greenhouse gas emissions.

“I’m telling you there is no such thing as adapting to climate change,” Dr Mora says. “When you have 1,000 different ways that you’ve got to protect yourself with climate change, forget about adaptation.”

He added: “We’re playing with fire. Do you want to play with fire? Go ahead and do all the climate change that you want,”

“But if there is a conclusion to be made from this, it’s that this is not something that we want to be messing with.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments