Global emissions cuts must be ‘10 times higher’ for world to meet climate goals

Stark findings come at ‘critical moment’ for global climate action, the study’s lead author tells The Independent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

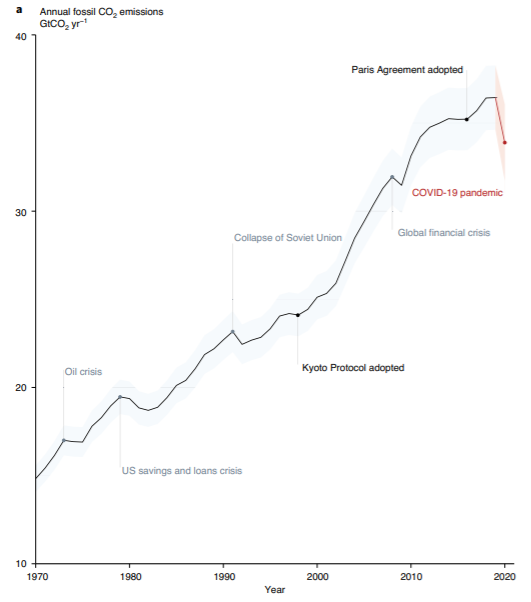

Your support makes all the difference.Global emissions cuts pre-Covid were just one tenth of the level needed to meet the world’s climate goals, a new analysis finds.

The research assesses the efforts that countries have taken to slash their emissions since the 2015 Paris Agreement, the global deal aimed at keeping global temperatures below 2C above pre-industrial levels.

It finds that, from 2016 to 2019, 64 countries reduced their emissions, while 150 countries continued to increase their rates of greenhouse gas pollution.

But even among the 64 countries that slashed their emissions, the scale of action was just a small fraction of what is required to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, according to the results.

Prof Corinne Le Quéré, a climate scientist at the University of East Anglia and lead author of the study, told The Independent: “If you only look at the countries where emissions decreased, you find the reductions are 10 times smaller than the cuts that we need to see in the next decade and beyond to tackle climate change.”

The research finds that, from 2016 to 2019, these 64 countries reduced their emissions by around 0.16bn tonnes of CO2 per year, on average, when compared to levels in 2011 to 2015.

But for the highest chance of meeting the Paris goals, global emissions need to fall by around 1-2bn tonnes of CO2 per year throughout the 2020s and beyond, the scientists said.

The results come from the Global Carbon Project, a group of climate scientists who have been tracking global emissions for two decades, and are published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The group of scientists also studied the impact of the Covid pandemic on global emissions.

The findings show that global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels fell by around 2.6bn tonnes from 2019 to 2020 – an unprecedented annual decline driven largely by lockdowns put in place to stop the spread of the virus.

This drop will cause global fossil fuel emissions to fall by almost 7 per cent from 2019 to 2020, according to results.

The decline in global emissions during lockdowns in 2020 mostly stemmed from there being fewer cars on the road, and, to a lesser extent, from slowdowns in industries such as manufacturing and metal production, the researchers said.

However, the dip in emissions in 2020 is unlikely to persist as the world emerges from the pandemic, they warned.

A separate analysis published by the International Energy Agency this week found that, while emissions fell overall in 2020, they began to rise steadily over the second half of the year as countries eased Covid restrictions. By December, emissions were 2 per cent higher than in the same month of the previous year.

The research reinforces the message that no country is currently doing enough to tackle the climate crisis, said Prof Le Quéré.

All countries are expected to come forward with more ambitious plans for tackling the climate crisis ahead of a key round of global talks, known as Cop26, which are to be held in Glasgow in November.

Prof Le Quéré added that economic stimulus packages aimed at helping countries recover from Covid-19 also provided a “critical moment” for taking action.

“There’s the possibility of aligning these investments with the investment that we need to tackle climate change, and many of these measures will create jobs and have benefits for air quality,” she said.

“The fundamental one is deploying renewable energy on a much larger scale. Then, there is also an opportunity to push very rapidly towards electric mobility or active transport, which is walking and cycling in cities.”

Dr Joeri Rogelj, a climate scientist from Imperial College London, who was not involved in the research, agreed that economic plans to recover from Covid offered “an important opportunity” for the world to take more urgent action on emissions.

“For this to happen, governments need to use their recovery stimulus in smart, future-proof ways,” he said. “Other analysis has shown very few governments are taking this opportunity at the moment.”

The findings highlight “the scale of the decarbonisation challenge we face and the need for utmost urgency”, added Prof Richard Pancost, head of the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, who was also not involved in the research.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments