World’s glaciers ‘contain 20% less ice than previously thought’

New estimates have profound implications for sea level rise and fresh water availability around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is 20 per cent less water contained in the world's glaciers than previously estimated, scientists have said, with the finding lowering the potential impacts of sea level rise due to the climate crisis.

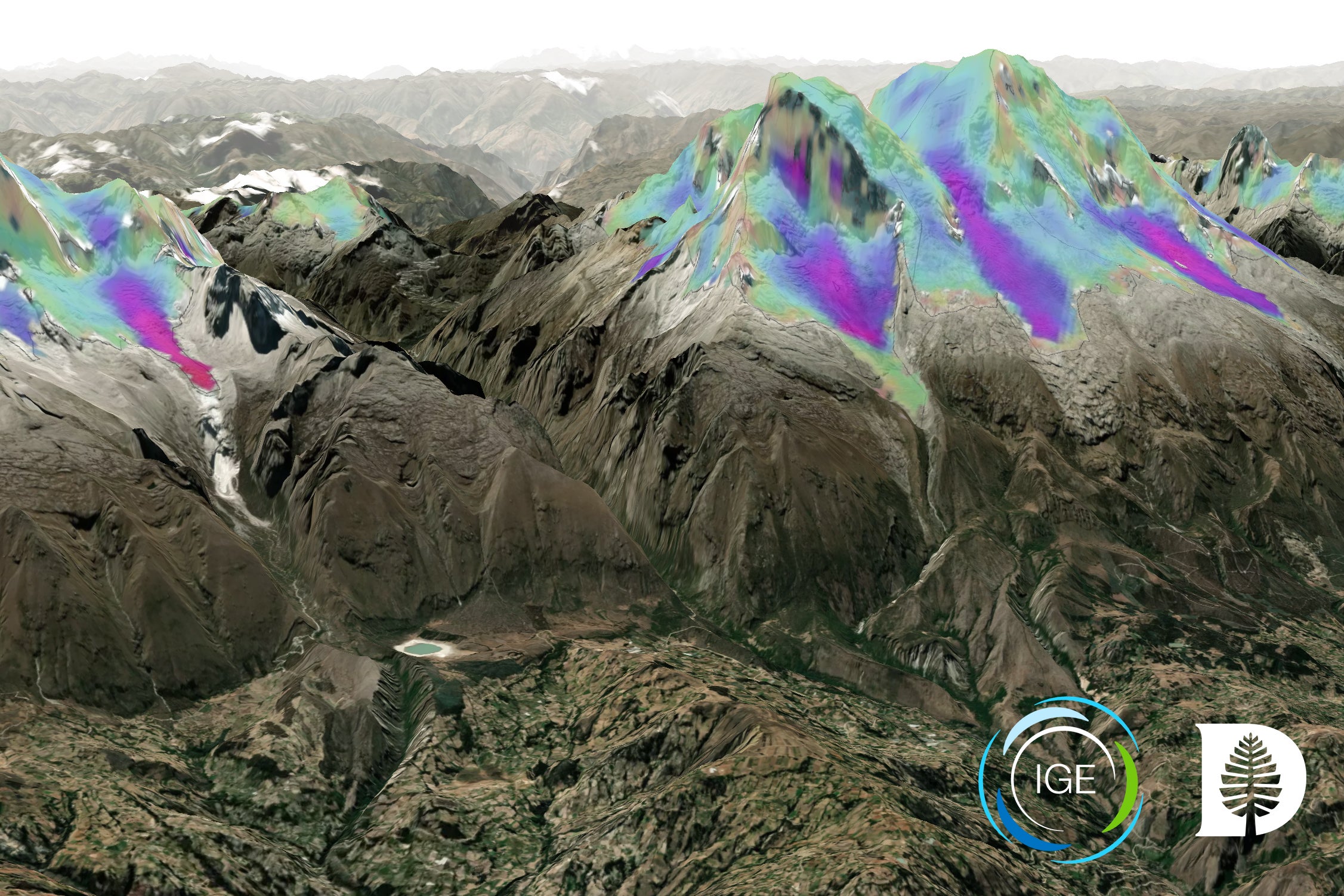

A new atlas – in which more than 250,000 glaciers around the planet are mapped with measurements recording their velocity and depth has revised earlier estimates of glacial ice volume, with a fifth less ice available to contribute to sea level rise.

The researchers said their findings also have implications for the availability of drinking water, as well as supplies of water for power generation, agriculture, industry and other uses.

Existing projections for climate-driven sea level rise will need to factor in the new data, so scientists can more accurately assess the risks to coastal-dwelling populations around the world.

Romain Millan, a postdoctoral scholar at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences in Grenoble, France, the lead author of the study, said: “Finding how much ice is stored in glaciers is a key step to anticipate the effects of climate change on society.

“With this information, we will be closer to knowing the size of the biggest glacial water reservoirs and also to consider how to respond to a world with less glaciers.”

Mathieu Morlighem, a professor of earth sciences at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire in the US, the co-author of the study, said: “The finding of less ice is important and will have implications for millions of people around the world.

“Even with this research, however, we still don’t have a perfect picture of how much water is really locked away in these glaciers”

The new atlas covers 9 per cent of the world’s glaciers. According to the study, many of these glaciers are shallower than estimated in prior research. Double counting of glaciers along the peripheries of Greenland and Antarctica also clouded previous data sets.

The study found less ice in some regions and more ice in others, with the overall result that there is less glacial ice worldwide than previously thought.

In South America’s tropical Andes mountains, the research indicated there is almost a quarter less glacial ice than previously thought.

This finding means there is up to 23 per cent less freshwater stored in an area from which millions of people depend during their everyday lives.

The reduction of this amount of freshwater is the equivalent of the complete drying of Mono Lake, California’s third largest lake, the scientists said.

Meanwhile, the Himalayas were found to have over a third more ice than previous estimates.

This means about 37 per cent more water resources could be available in the region, although the scientists warned that Asia's glaciers are now melting quickly.

“The overall trend of warming and mass loss remains unchanged,“ said Professor Morlighem.

“This study provides the necessary picture for models to offer more reliable projections of how much time these glaciers have left.”

The melting of glaciers due to the climate crisis is one of the main causes of rising sea levels. It is currently estimated that glaciers contribute 25-30 per cent to overall sea level rise, threatening about 10 per cent of the world's population living lower than 30 feet above sea level.

The scientists said a 20 per cent reduction of glacial ice available for sea level rise lessens the potential for glacial contribution to sea level by 3 inches (7.6cm), revising it downward from 13 inches (33cm) to just over 10 inches (25cm).

This projection includes contributions from all the world’s glaciers except the two large ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, which have a much larger potential contribution to sea level rise.

“Comparing global differences with previous estimates is just one side of the picture,” said Dr Millan.

“If you start looking locally, then the changes are even larger. To correctly project the future evolution of glaciers, capturing fine details is much more important than just the total volume.”

The research team said a key reason for the major change to glacier volume estimates is that depth measurements previously existed for only about 1 per cent of the world’s glaciers, with most of those glaciers only being partially studied.

The glacial ice estimates that did exist prior to the new study were “almost entirely uncertain”, they said.

The uncertainty is due, in part, to the lack of ice flow measurements showing the location of thick and thin ice, all of which is gathered through indirect techniques.

In order to create the massive ice flow database, the research team studied more than 800,000 pairs of satellite images of glaciers, including large ice caps, narrow alpine glaciers, slow valley glaciers and fast tidewater glaciers. The high-resolution images were acquired between 2017-18 by NASA’s Landsat-8 and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites. The data was processed using more than 1 million hours of computation at IGE.

“We generally think about glaciers as solid ice that may melt in the summer, but ice actually flows like thick syrup under its own weight,” said Professor Morlighem.

“The ice flows from high altitude to lower elevations where it eventually turns to water. Using satellite imagery, we are able to track the motion of these glaciers from space at the global scale and, from there, deduce the amount of ice all around the world.”

The work has resulted in the first global map of ice flow velocities covering most of the world’s terrestrial glaciers, including regions where no previous mapping existed, such as the southern cordilleras (mountain ranges) of South America, sub-Antarctic islands, and New Zealand.

But the scientists said that there were still considerable uncertainties about the world's glaciers as the thickness distribution of glaciers is still subject to large gaps of information.

“Our estimations are closer, but still uncertain, particularly in regions where many people rely on glaciers,” said Dr Millan.

“Collecting and sharing measurements is complicated, because glaciers are spread throughout so many countries with different research priorities.”

The team said that without direct field measurements the estimate of glacier freshwater resources will remain uncertain.

The scientists said they are calling for a re-evaluation of the evolution of the world’s glaciers in numerical models as well as direct observations of ice thicknesses in the tropical Andes and the Himalayas, which are major water towers and remain poorly documented.

The research is published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments