Glaciers are disappearing – and scientists are in a race against time to understand the environmental impact

When ice melts it doesn’t just alter the landscape; it changes the complexion of the water and causes major disruption to ancient ecosystems. Henry Fountain reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The ice cream stand is long gone, and so is the ice. The glacier now ends more than a mile farther up the mountain.

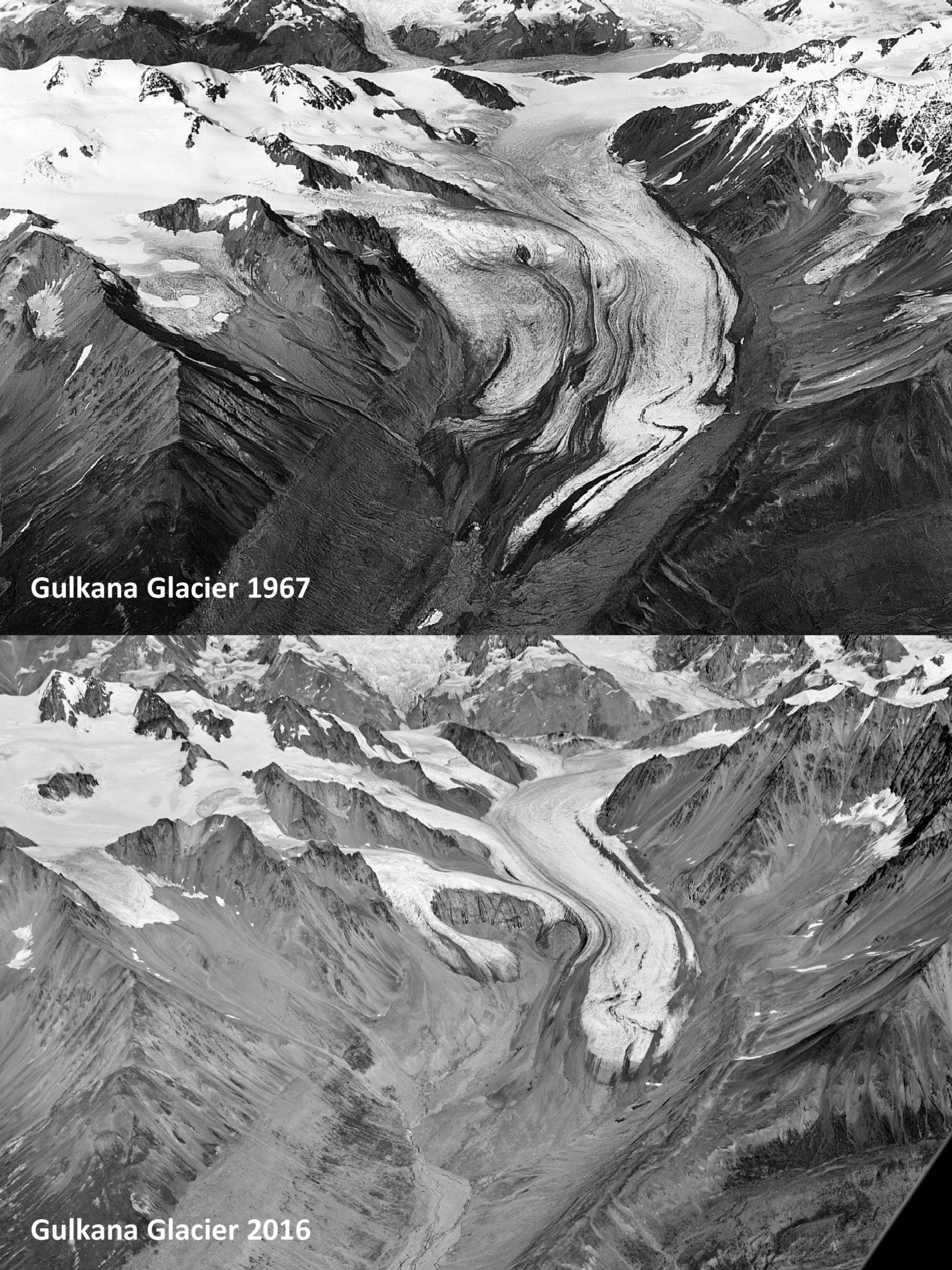

As surely as they are melting elsewhere around the world, glaciers are disappearing in North America, too.

This great melting will affect ecosystems and the creatures within them, like the salmon that spawn in meltwater streams. This is on top of the effects on the water that billions of people drink, the crops they grow and the energy they need.

Glacier-fed ecosystems are delicately balanced, populated by species that have adapted to the unique conditions of the streams. As glaciers shrink and meltwater eventually declines, changes in water temperature, nutrient content and other characteristics will disrupt those natural communities.

“Lots of these ecosystems have evolved with the glaciers for thousands of years or maybe longer,” says Jon Riedel, a geologist at the US National Park Service, who has established glacier-monitoring programmes at Rainier and other parks. “We’re pulling this thing apart but we don’t really understand the impacts.”

Among the researchers trying to understand the disruptions is J Ryan Bellmore, a biologist with the US Forest Service in Juneau, Alaska. He studies freshwater food webs, the complex what-eats-what relationships that show, in effect, how energy moves through an ecosystem. Often that involves examining the stomach contents of fish.

Alaska is an ideal place to study the effects of climate change on glaciers, since there are thousands of them and overall they are losing some 75 billion tons of ice every year. As the ice melts it leaves an altered landscape, and the water that runs through the landscape changes as well.

One day, late last autumn, Bellmore and a colleague set fish traps in the Herbert river, about 10 miles north of the centre of Juneau. The river meanders for a few miles from the glacier of the same name to its outlet on the coast.

Bellmore wants to know what fish eat in the Herbert, a river that consists almost entirely of glacial meltwater, compared to what they eat in other nearby rivers where the flow comes from other sources. Water temperatures differ depending on the source, as do concentrations and types of nutrients and the clarity or cloudiness of the water. All of that has a bearing on the type of food available and the overall health of the ecosystem.

Studying food webs in different kinds of streams will lead to a better understanding of what will happen as glaciers like the Herbert continue to retreat and meltwater flows eventually decline, replaced by water from other sources.

“As glaciers recede, glacial streams may look more like snowmelt streams, or rainfall streams,” Bellmore says. “What unique characteristics are going to go away when we lose these glacial streams?”

One thing that may be lost are specialised communities of organisms. Streams that are mostly fed by glacial meltwater often have unique species adapted to the cold conditions. Reducing or eventually eliminating the contribution of this meltwater will raise stream temperatures. Even a small temperature increase can have potentially negative effects.

“Certain species like cold water,” says Alexander Milner, a professor of river ecosystems at the University of Birmingham, in England, who has studied the changes wrought by shrinking glaciers for years. “When the glaciers disappear, those species will go extinct.”

Milner is talking about small creatures like insects or even microorganisms like bacteria. The effects on larger species like salmon and other fish may be more complex – and, in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, of more pressing concern.

Lots of these ecosystems have evolved with the glaciers for thousands of years

“In this part of the world salmon are just really important for economies and cultures,” says Jonathan Moore, an ecologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. With other researchers in the United States and Canada, Moore has formed a group to more closely study the links between salmon and melting ice.

Salmon and similar fish are born in freshwater streams, then head to sea to grow, often for years, before returning to fresh water to spawn and die. Water temperatures must be just right for salmon to develop, so, as glacial meltwater declines and stream temperatures rise, populations may be affected.

But other changes may be beneficial, at least for a while. As glaciers retreat, they leave boulders, gravel and sediment, and streams running around them. The gravel beds and meanders can be ideal places for salmon to lay their eggs during spawning season.

In some places there may be huge gains in salmon habitat, says Kara Pitman, a Simon Fraser doctoral student in the group who is modelling how and where habitats increase as glaciers shrink. In some areas of British Columbia, she says, “in 25 or 50 years, watersheds may be full of salmon”.

But overall, the gains might not be so great, given the other changes affecting the fish. “It’s more that salmon populations could be redistributing,” colonising new areas and abandoning others, she says. “Salmon do have an amazing ability to adjust and adapt.”

“We’re trying to understand the new opportunities for salmon,” Moore says, “but fully acknowledge that climate change overall is not good for salmon in most places.”

The melting that leads to habitat changes for salmon can happen over years or decades. But shrinking glaciers can also lead to floods or debris flows that can alter streambeds in an instant. Many of the rivers and creeks in Mount Rainier National Park, for instance, have been hit by floods over the years.

The natural history of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, and of other parts of the world with glaciers, can be seen as a story of disruption caused by ice, slowly or quickly.

It happened in the past, during the last ice age, when the movement of the huge ice sheets that covered much of the planet reshaped the land. And it’s happening today, as glaciers, the remnants of those ice sheets, retreat.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments