Warning over rapid rise in fungal attacks posing ‘catastrophic’ threat to global food supply

Global heating may intensify ‘perfect storm’ fuelling world’s largest threat to crops

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

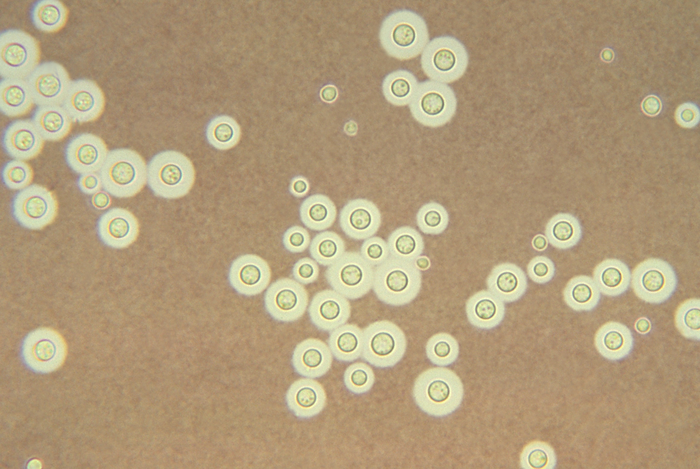

Your support makes all the difference.A rapid rise in fungal attacks on crops – exacerbated by climate breakdown – could become a “catastrophe” for the world’s food supply, scientists have warned.

Already the most important threat to crops worldwide, fungal infections are estimated to destroy 10 to 23 per cent of farmers’ annual output, plus a further 10 to 20 per cent post-harvest, spoiling enough wheat, rice, maize, potato and soybean to feed up to 4 billion people 2,000 daily calories for a year.

But in a paper published in the leading journal Nature, scientists have cautioned that the “perfect storm” of food production techniques which has fuelled the current situation could be intensified even further by rising temperatures.

Global heating means that plant pathogens – including fungi – previously confined to southern regions are now spreading towards the north pole, with fungal infections estimated to be moving northwards at a rate of some 7 kilometres per year since the 1990s.

In one such example, farmers have already reported wheat stem rust infections, which typically occur in the tropics, in Ireland and England.

The scientists warned that rising temperatures could also cause fungi already living harmlessly in plants in colder countries to become pathogenic – and may make soil-dwelling pathogens more capable of leaping from plants to infect warmer hosts, such as animals and humans.

Fungal pathogens are thought to claim at least 1.5 million lives each year, close to the number killed by malaria and TB, prompting the World Health Organisation to warn in October that they are becoming “increasingly common and resistant to treatment”.

While the UN health agency cited climate breakdown and human trade and travel as driving the increase in human infections, the new study points to agricultural practices in providing “perfect” conditions for fungi to infect crops.

Describing the threat to plants as “another major threat to human health” – alongside that which fungi pose directly to humans, particularly among those with weakened immune systems – the authors warn that united global action is needed to tackle the issue.

“Fungal infections are threatening some of our most important crops, from potatoes to grains and bananas,” said co-author Professor Sarah Gurr, of the University of Exeter. “We are already seeing massive losses, and this threatens to become a global catastrophe in light of population growth.

“Recently, we’ve seen the world unite over the human health threat posed by Covid. We now urgently need a globally united approach to tackling fungal infection, with more investment, from governments, philanthropic organisations and private companies, to build on the seeds of hope and stop this developing into a global catastrophe which will see people starve.”

Fungi are incredibly resilient, and the spores of some species can remain viable in soil for up to 40 years, while the airborne spores of other species – such as wheat stem rust – can travel between continents, according to the authors.

They are also said to be extremely adaptable, with “phenomenal” genetic diversity between and among species.

Modern farming practices, in which genetically uniform crops are farmed in vast areas, “provide the ideal feeding and breeding grounds for such a prolific and fast-evolving group of organisms”, the paper warns.

Furthermore, the increasingly widespread use of antifungal treatments which target only a single cellular process in fungi has led to the emergence of fungicide resistance, the authors say.

While the authors – Prof Gurr and Professor Eva Stukenbrock, of Germany’s Kiel University – warn of the possibility for “catastrophe”, they also say there is cause for hope.

They point to new research at Exeter which could pave the way for more complex antifungal treatments far less likely to fuel fungicide resistance, and a Danish study with promising results in which farmers planted seed mixtures containing a range of fungal-resistant genes.

Technology may also prove crucial, with AI, citizen science and remote sensing tools such as drones allowing for early detection and control of outbreaks, said the authors, who called for more investment into fungal crop research.

“Addressing the greatest threats to food security – and so to human health – must include tending to the devastating impacts fungi are having, and will keep having, on the world’s food supply,” they wrote.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments