Why climate change could make flights a whole lot bumpier

The layer of atmosphere closest to Earth, the troposphere, has been rising by around 164ft per decade

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The climate crisis is causing changes in earth’s atmosphere that may have consequences for turbulence levels on flights.

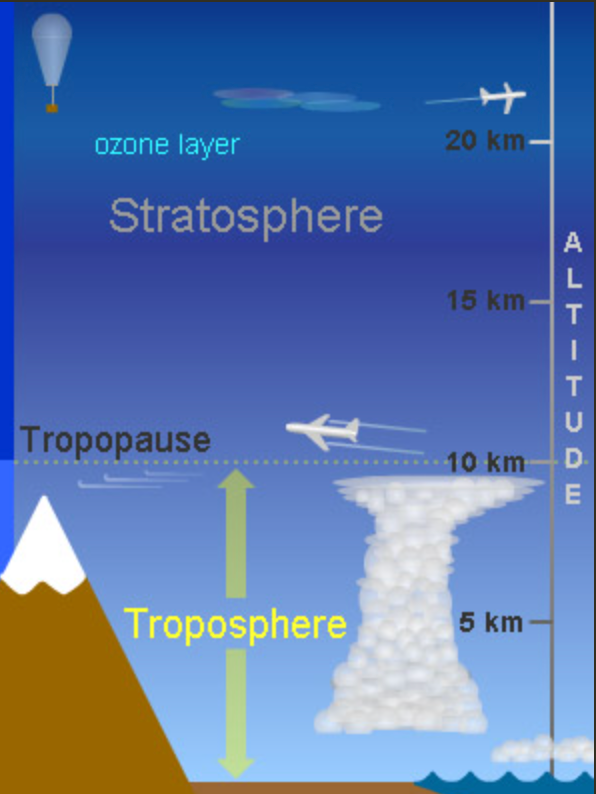

New research, published this month in Science Advances, discovered that as the planet heats up, the troposphere – the layer of atmosphere closest to Earth where we live – has been rising by around 164 feet (50 metres) per decade.

The troposphere stretches up for about five to nine miles (8-14km) and varies in different parts of the globe. It’s thickest around the equator and has its thinnest points at the poles.

Above the troposphere, sits the stratosphere, a more stable layer which stretches to a height of 31 miles (50km) and encompasses the ozone layer.

The changes may have real-world consequences when it comes to the aviation industry. Airline pilots typically fly in the lower stratosphere to avoid the turbulence dreaded by many passengers.

Turbulence is caused by eddies of “rough air” and is often compared to choppy waves at sea. There are several reasons for turbulence: shear (when pockets of air move passed each other in different directions); mechanical (a mountain or large structure disrupts air flow), or thermal (when warm air rises through cooler air).

Therefore, as the troposphere’s upper boundary – called the tropopause – rises, it may mean that pilots have to fly higher to avoid bumpy, rough air.

While earlier studies have shown that the tropopause is rising, it was not only linked to climate change but stratospheric cooling associated with the thinning of Earth’s ozone layer.

Several international agreements put in place to phase-out use of ozone-depleting chemicals have been successful in reversing this, and stabilising temperatures in the lower stratosphere. The new study looked at the latest data to understand why the tropopause is still rising regardless.

The international team of researchers, led by Nanjing University in China, deployed weather balloons to take upper air observations over the past 40 years in the Northern Hemisphere.

The expansion of tropopause height, according to the study, is “further observational evidence for anthropogenic [or man-made] climate change”.

Bill Randel, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and study co-author, called it an “unambiguous sign” of changing atmospheric structure.

“These results provide independent confirmation, in addition to all the other evidence of climate change, that greenhouse gases are altering our atmosphere,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments