A decade on, the continuing tragedy of Deepwater Horizon and fears it could happen again

On April 20, 2010, an explosion on the drilling rig off the Louisiana coast left 11 workers dead and 17 crew members injured. The environmental impacts were catastrophic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ten years on, the call about the Deepwater Horizon explosion is etched in Julian MacQueen’s memory.

“It was one of those moments you remember, like where you were on 9/11. I was at a convention in Scottsdale, Arizona and I got a call from my operations manager. We thought, well that’s a hundred miles away, it’s not going to affect us that much,” he told The Independent.

Like many others in the Gulf of Mexico, for hotelier Mr MacQueen, who has coastal properties in the region, it was a matter of time. “I’m a pilot so I flew out to the rig and I could see the plumes of oil. It was like that old Fifties movie, The Blob. It was coming and it was going to get you.”

On April 20, 2010, night had fallen off the coast of Louisiana, when high-pressure methane gas rose to the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig above and exploded into a fireball that could be seen from 40 miles away.

The disaster left 11 workers presumed dead, their bodies never found despite a three-day search by the coastguard. Another 17 of the 126 crew onboard were injured.

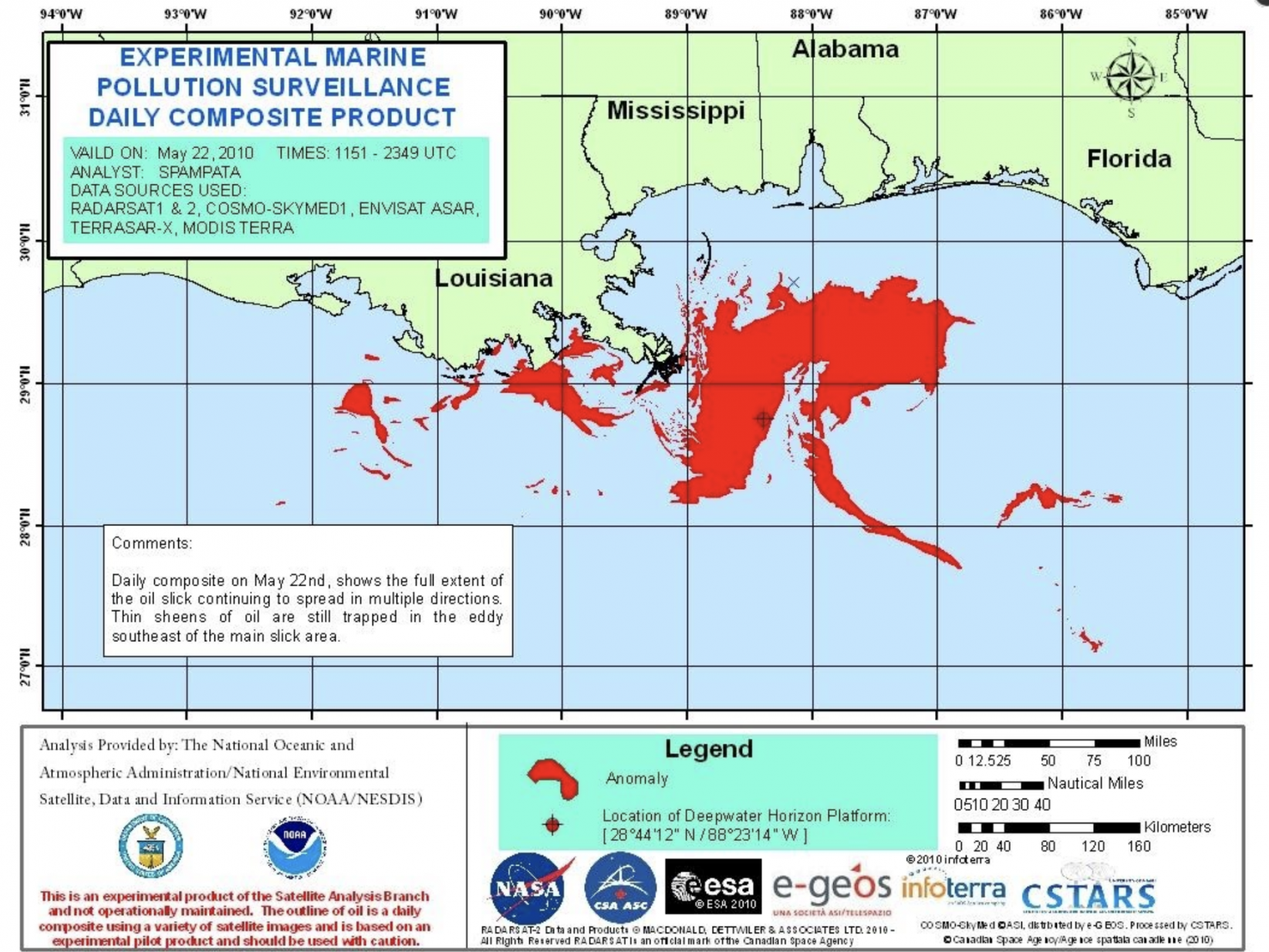

The fire was inextinguishable and two days later, the rig sank. The ultra-deepwater well at BP’s Macondo Prospect, where Deepwater Horizon had been drilling, spewed an estimated 134 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico before it was capped.

Then-president Barack Obama called it “the worst environmental disaster America has ever faced”.

The fallout was catastrophic: 1,300 miles of coastline from Florida to Texas, was impacted, killing tens of thousands of marine mammals and fish, and decimating livelihoods in the seafood and tourism industries. The cost of the damage ran to tens of billions of dollars.

A decade on, a group of scientists, conservationists and locals spoke to The Independent about the devastating toll of the oil spill and the impacts that are still being felt today.

All of them fear that this could happen again.

In recent years, President Trump‘s focus on boosting US oil production has led to an easing of safety rules put in place by the Obama administration after the Deepwater Horizon spill.

Professor Tracey Sutton researches the ecology of the Gulf at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. His research assessing damage to species in the deepwater column of the ocean began in the months after the disaster.

“Oil was in all of the deepwater column at some point,” he said. “Roughly half made it to the surface and some made it to the bottom. The effects were quite severe.”

When plants and animals on the ocean surface die and decay, they descend to the sea bed, mixing with other particles including sand and soot to form “marine snow”, consumed by microbes and zooplankton.

“The dispersed oil glommed on to marine snow and we think that’s one way it’s persisted in the environment,” Professor Sutton said. “A lot of those particles with oil could have gotten into the food web and the bottom gets stirred up periodically, resuspending particles back up in the water.

“We tested the bodies of many deep-sea animals and females’ eggs. In 2017, we were still finding oil contaminants in the eggs above levels known to be sublethal for animals. We also saw an overall decline in animal numbers.”

Professor Sutton and his team continue to analyse samples from 2018. Their next research trip begins in August and will assess damage for another five years in the Gulf.

Diane Hoskins, campaign director of conservation non-profit, Oceana, said that devastation from the oil spill lingers in the Gulf.

“A recent study showed the seafloor near the wellhead is barren of life typically found there. Scientists even described it as a toxic waste dump,” she told The Independent.

“Many marine mammal populations will take decades to recover, if they do. Some wetlands killed by oil will never recover because the plants died and the land washed away with it.”

Details of one study, published last week, found that all fish in the region suffered from the effects of the pollution.

The devastation of the marine ecosystem has had a knock-on effect for those whose lives revolved around the ocean.

Daniel Le is branch manager of Boat People SOS in Biloxi, Mississippi. The Vietnamese-American advocacy group, established in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, provided assistance to Vietnamese seafood workers following the oil spill.

He told The Independent: “It had a devastating impact. About 85% of our Gulf coast members are in the seafood industry.

“April is the month that the fishing community gets ready for. It’s a new season, people are excited and out on the docks, prepping the boats.” Back in 2010, he said that they were unprepared for the magnitude of the spill.

“Within days, the whole fishing industry shut down on the Gulf Coast,” Mr Le said.

“There was a lot of anxiety. A lot of people depended on fishing to eat as well as selling to the local market. For months, people weren’t able to work. Once the conditions got a little better, people went back out but there were reports of shrimp with oil in their gills. Oil was getting stuck in the nets.

“A number of shrimp fishermen reported that the catch was significantly reduced and many of the species were dead.

“A lot of people didn’t want to eat Gulf shrimp because of fears of contamination. Fishermen couldn’t sell their catch but there wasn’t a lot of catch to make a living with anyway.”

Mr MacQueen, who founded Innisfree Hotels, described the effect that the disaster had on the community of Pensacola, Florida, where his chain’s Hilton hotel sits directly on the beach.

“I called my insurance company to see what was available for business interruption and there was nothing. No one had any coverage for this kind of event,” he told The Independent.

“Everyone was completely exposed financially. I spent the next five months essentially shut down.

“There were no reservations being made. The idea of the oil, more than the oil itself, was what kept everybody away. We were done and there was nothing we could do about it.

“We made 60% of our revenues during the summer season. Normally at the peak, on Fourth of July, we have several thousand people on the beach. In 2010, there were maybe a dozen people.

“The ripple effect goes deep into the community. We’re the largest, privately-held taxpayer in the area. It trickled down to where the board of education had to lay teachers off because we weren’t generating the taxes that they depended on.

“In our area, we determined that for every dollar spent at the hotel, [tourists] spend another $10 in the communities. We laid off hundreds of people. It was devastating for Pensacola and everything that depended on beach tourism.”

Mr MacQueen believes that it is fallacy to think about when business got back to normal. “We look at 2017 as when we felt like we were getting back to normal. It took seven years.

“However when there’s an event that takes you down significantly and you start to build back up to where you were before, what you don’t take into account is, what would have happened if that trend before the event had continued?

“The idea of getting back to where you were, I think, is a false premise. It’s almost saying things were less worse.”

The repercussions are still being felt along the Gulf Coast where the disaster remains deeply-ingrained in the collective psyche.

Mr MacQueen said: ”It’s unspoken in many respects but the overall negligence that was displayed, and then further displayed in the movie that came out, built on the psyche of the community.”

Mr Le said that a hopelessness seeped into the fishing communities.

“We are ten years removed and people think everything should be back to normal but that’s not true at all,” he said.

“For the past two or three years, for the peak fishing season, 50% to 75% of the small fishing fleet were idle because there weren’t shrimp, crab or oysters to be harvested.

“It has really taken a toll on the mental health of our community. Some 30% of our members left fishing because it’s no longer viable. These folks don’t have a transferable job skills. Fishing is the only thing they know, so they have to move to different states to find other jobs.”

The lack of data in the Gulf of Mexico, and in deep-sea research generally, means that it may never truly be known what was lost.

Professor Sutton said: “Although industry is going deeper for resources, I think what’s most important to note is that we haven’t done the pre-assessment to develop baselines of what a normal condition is in deep sea.

“Deepwater Horizon highlighted the fact that we had no data whatsoever for what lived at the depths of the Macondo wellhead. You can’t really do a damage assessment if you don’t have any data.”

Professor Sutton points to a lesser-known story: That the Deepwater Horizon spill could have been a lot worse due to the Loop Current, a “conveyor belt” of water that flows between Cuba and the Yucatan peninsula, moving north into the Gulf of Mexico.

He said: “The Loop Current occasionally reaches far up into the Gulf, into the footprint of the oil spill. It just so happened that in 2010 the Loop Current wasn’t that far north.

“Had it been, it would have carried oil straight through the Florida Keys and painted the coral reefs. Oil residue was detected in the water at the Keys but it could have wiped them out and those reefs would have never come back.”

In September 2014, US District Judge Carl Barbier in New Orleans ruled that BP’s operations at Deepwater Horizon were “reckless” and that willful misconduct and gross negligence led to the disaster.

BP was assigned an 67% of the fault. The rest of the responsibility was apportioned to Transocean, which owned the rig, and oil services company, Halliburton, 30 percent and 3 percent, respectively.

BP and its partners will have spent more than $50bn in the end, to cover cleanup costs and settlements following the disaster, according to Reuters.

Ms Hoskins authored a recent report on the disaster and came to the conclusion that no lessons had been learned.

She said: ”Today, off-shore drilling remains dirty and dangerous and the industry’s record is unacceptable.

“Instead of learning from this disaster, President Trump is proposing to radically expand offshore drilling while dismantling some of the few protections put in place as a result of the catastrophe.

“The key lesson was that the industry cannot be trusted to self police.

“In response to the disaster, the Obama administration enacted safeguards. Last year, President Trump drastically gutted them, rolling back the frequency and duration of testing for blowout preventers, the device that failed on Deepwater Horizon. There has also been a weakening of onshore monitoring requirements and reducing government oversight to evaluate industry safety.

“The ramifications of offshore drilling are horrific and catastrophic when things go wrong. These [safeguards] should be the minimal standard of doing business.”

All seven members of the bipartisan commission set up in the aftermath of the disaster and to stop another like it happening told The New York Times that many of their recommendations were not taken seriously and the risk of another spill is possible.

The number of safety inspection visits by the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, established after the 2010 spill, went down by more than 20% over the past six years in the Gulf, according to a review by the Associated Press.

However officials point to an increase in checks of electronic records, safety programmes and individual oil rig components.

In a statement, BP said: “The Deepwater Horizon accident forever changed BP. We will never forget the 11 people who lost their lives, nor the damage caused. In 2010, we committed to help restore the Gulf region economically and environmentally as well as to become a safer company. The Gulf has recovered well and the lessons we learned and the changes we made — from tougher standards to better oversight — are the foundation of our culture of care. A decade later, we are proud of how we honoured our commitments but remain keenly aware that we must always put safety first.”

Mr MacQueen said: “I’m appalled that there has never been anyone held accountable. I’m appalled that there had been no significant oversight changes in how the regulators are working on controlling this in the future.”

Those who felt the impacts of Deepwater Horizon a decade ago are left with fears that it will happen again.

Professor Sutton said: “The Gulf of Mexico is incredibly diverse and we now know maybe more about it than any other deep-sea system in the world’s oceans. It just sucks that it took an oil spill is my impolite way of saying it.”

He added: “The majority of US oil comes from ultra-deep wells in the Gulf of Mexico. There are leases all the way down to 3,000 metres. Deepwater Horizon was half that.

“This is not a problem that’s going to go away. Another deepwater spill is still very much a real possibility.”

As oil companies drill deeper, the risks increase due to ultra-high pressures and oil temperatures that can top 350F.

Ms Hoskins said: “President Trump has proposed the most radical expansion of offshore drilling that ever been proposed by a president. Under his plan, areas that don’t have offshore drilling would open up — on the east and west coasts and even closer to Florida’s Gulf coast.

“It’s outrageous, especially when you consider all the coastal economies that rely on a clean and healthy ocean. Protecting our ocean can ensure that those industries thrive for decades to come. When the oil runs out, so do the jobs.

“One hopeful thing is that every governor opposes drilling off their coast. Now it’s time for President Trump to listen.”

Mr Le said: “People see all these rigs out there but what are they protocols in place to make sure it doesn’t happen again? There’s a fear of another disaster if the government doesn’t tighten regulations.”

Mr MacQueen said: “I fly back and forth from the panhandle of Florida to New Orleans and on a clear night in the Gulf of Mexico, there’s so many oil rigs that on the horizon, you can’t tell which is which from the stars in the sky and what appears to be stars on the ocean.

“I know it’s going to happen again. The idea that the current administration is re-leasing and planning out leases for the overall industry is completely disgusting.

“What’s heartening, at least in Florida on both sides of the aisle, there’s been unanimous support for not letting that happen.

“I’m hoping that at the federal level we have enough common sense to know that supply of oil and the demand for it are going in opposite directions.

“In my mind, it’s extraordinary overreach to go into the pristine waters off the Florida coast to find even more oil that is not necessary at this time. We’ve got so many other options in front of us.”

Associated Press contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments